![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, January 24, 2019 — “Come on, get on because we’re leaving…” Thus the microbus driver addresses the only client who this Tuesday morning is at the stop at 1st and 70th street in Havana. The news of the recently inaugurated Route 15 doesn’t seem to have yet reached the inhabitants of the capital, where for decades getting from one point to another has been a headache.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, January 24, 2019 — “Come on, get on because we’re leaving…” Thus the microbus driver addresses the only client who this Tuesday morning is at the stop at 1st and 70th street in Havana. The news of the recently inaugurated Route 15 doesn’t seem to have yet reached the inhabitants of the capital, where for decades getting from one point to another has been a headache.

Immaculate, the seats without a spot of dirt, the new little buses arrived from Russia, are the Government’s latest bet in its attempts to get private transport off of Havana’s streets. In the domain of the almendrones [classic American cars, mostly from the 1950s, typically used as private taxis] and the pisicorres [vans or trucks adapted to transport passengers], these 12-seat vehicles stand out and provoke more than one prediction. continue reading

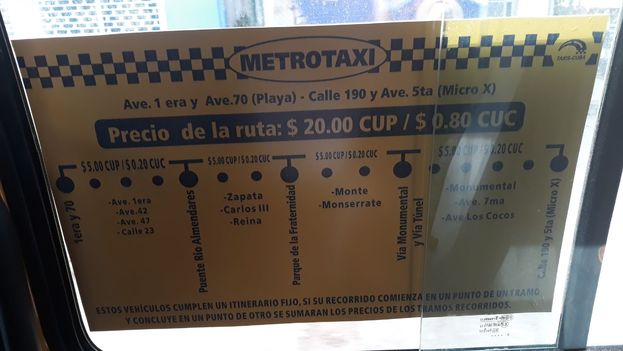

On the route, which begins in Playa and ends in Alamar via Avenida Carlos III and the Monumental, a few passengers get on. The majority ask loudly how long this new experiment will last: “We’re going to see in six months how they are,” is the sentence most repeated by the incredulous riders.

At the stop in the Playa municipality, only one stand with the information for the routes gives away the beginning of “operation microbus,” as some jokesters have nicknamed the new routes. With only one passenger, the driver starts up before the curious glances of passersby.

The passenger, somewhat astonished to be traveling so comfortably inside the vehicle, spends part of the journey reading all the posters inside with the details of prices for stretches of routes, streets through which the microbus travels, and the stops it makes. “That’s so that everyone knows what they have to pay and nobody is ripped off,” thinks the rider while a mother and child get on at a stop.

“It smells new, Mommy,” lets out the boy as soon as he smells the aroma of recently-opened merchandise that still fills the microbus. “We’ll see how it smells in a few months,” responds the mother. The skepticism turns into the “stone passenger” along the majority of the route, as if riders would prefer to not to get too hopeful.

Made by the Russian company GAZ, the vehicles run between 6:30 am until 10:00 pm and share stops with almendrones whose owners, a few self-employed drivers, have decided to accept the new rules of the game.

In December the government approved a package of measures to regulate the work of private drivers. Among the new measures is the obligation to establish stops, travel on determined routes, and buy fuel with a magnetic card that allows a greater control on spending and consumption*.

The new rules generated a great dissent among the drivers, who pressured authorities with a strike for several days. As of that moment the flow of private taxis hasn’t stablized again and the Government has kept up the battle of wills with them by importing and putting into service new state vehicles.

The confrontation has challenged the entire city, where an average of almost a million and a half people move about each day, of which a million do so on State-owned buses. With an evident decrease in private drivers, Havanans had an end of the year “where everything collapsed at the same time,” the mother with her son on the microbus laments this Tuesday.

“The lack of flour and eggs, the rise in prices, and also the problems getting around,” explains the woman. “Now we have these microbuses but there’s no chicken anywhere,” she adds with an annoyed look. “It’s like we can’t have complete happiness, either we can get around or we can eat.”

At the top of Calle 42, the microbus now carries six people. A lady with a box full of onions, two young people who only take photos of the interior to put them on Instagram with sepia- and rose-colored filters, the passenger who got on at the beginning of the route, and the mother with her son, who at this point breathes on the window to draw little circles with his finger.

Next to the driver, the conductor is tasked with charging for the passage, which varies according to the stretch traveled. “To travel the entire route, you pay 20 pesos,” exclaims the elderly lady with the onions. “I thought that there was going to be a real reduction but prices are still very high for people.”

After the fascination of the first moment and the happiness of traveling in a clean and new bus passes, the passengers dedicate themselves to complaining about the prices of life.

The driver tries to calm the mood by saying that the advantages of the equipment cannot be denied. “These cars just arrived, I took the plastic off these seats and you all are using it for the first time,” says the driver at the top of Puente Almendares.

A young resident of Alamar recognizes that until then he had to take three cars to get to his grandfather’s house in Playa, but he doesn’t believe he could be a steady client of the microbuses because “you can’t spend 20 or 40 pesos every day on transportation.” He also complains that the initiative still wasn’t well organized and in East Havana he had seen a line of vehicles that were going out “one after another instead of doing it in a staggered way so that it would be more efficient.”

A yell from the lady with the onions interrupts him: “Stop!” she orders the driver. “I’m getting off here, I see that they [the stores] have oil.” With the sudden stop, some onion skins fall on the impeccable upholstery of the seats, and the door opens to return to a reality without novelties.

*Translator’s note: In other words, it prevents drivers from buying fuel on the black market because their purchases from the government are tracked on the card and inspectors can check if they bought enough fuel to operate the miles traveled.

Translated by: Sheilagh Carey

________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.