![]() EFE (via 14ymedio), Ana Menghotti, Miami | November 24, 2019 — Twenty years ago the “little rafter” Elián González was saved from drowning, as his mother and other Cubans who were trying to reach Florida had, but was left in a tug-of-war between the Cuban government and the exiles in Miami. The tug-of-war was settled with an American court decision that made possible his return to the island.

EFE (via 14ymedio), Ana Menghotti, Miami | November 24, 2019 — Twenty years ago the “little rafter” Elián González was saved from drowning, as his mother and other Cubans who were trying to reach Florida had, but was left in a tug-of-war between the Cuban government and the exiles in Miami. The tug-of-war was settled with an American court decision that made possible his return to the island.

“I would again defend a defenseless child against a dictatorship,” said Ramón Saúl Sánchez, one of the leaders of the protests in which Cubans in Miami fruitlessly tried to stop Elián, who was five when he crossed the Florida strait aboard a raft, from being returned to his father and to Cuba.

“It was an ethical duty, we didn’t do it out of politics or for any other reason. Whoever has gone through an experience like us (the exiles) knows that we were obligated to defend that boy,” adds the leader of the Democracy Movement.

In front of the house in Little Havana where the boy lived with a maternal aunt and other family members after his rescue by fishermen in waters near Florida on November 25, 1999, Sánchez recalls the blow that he received in that house on that day US federal agents burst in to take Elián.

It was April 22, 2000 and the warrant had been given by Janet Reno, then the attorney general of the US and for many exiles the “bad guy” in this “film.”

That day Sánchez found out that the slogan “Elián isn’t leaving,” which had been popularized in the protests, wasn’t going to be reality.

Considered in Miami a “miracle” boy not only for having been saved from the shipwreck but also because his rescue was on the day of Thanksgiving, Elián González, was turned into a symbol of the Revolution and its triumph over capitalism, and returned to Cuba on June 28, 2000 after many negotiations and to-ing and fro-ing in the courts and mass demonstrations in Miami and on the island.

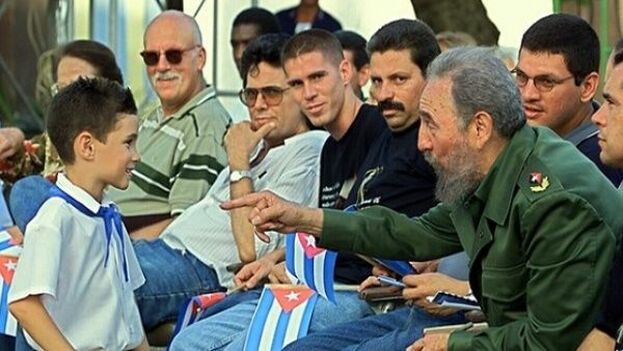

Fidel Castro personally became involved in what in other circumstances and countries would have been only a family dispute over the custody of a child whose mother took him from the country without the permission of the father, who wanted to get him back and raise him in Cuba.

Sánchez believes that Castro, knowing that in the United States the “law is respected,” took advantage of the Elián case to “project himself as a defender of childhood,” although “he wasn’t,” while at the same time “deal a blow of international dimensions to the exile community.”

The organizer of “human chains” and actions of “civil disobedience” for Elián says that he always thought that it was the maternal and paternal family members of the boy who should have come to an agreement about his future, not the governments.

However, he says, there was a fact that couldn’t be forgotten: Elián’s mother decided to leave a country in which “a dictatorship was suffocating, and is still suffocating, the people.”

If Cuba wasn’t “a dictatorship,” the people wouldn’t embark upon the sea, says Sánchez, who blames the “regime” for every one of the deaths of Cuban rafters whose “American dream” ended when the precarious boat on which they abandoned their country foundered.

The so-called “rafter crisis” was in 1994, but in 1999, the year in which Elián’s raft foundered, there was another massive departure of precarious boats toward the US without the Cuban government trying to stop them, according to information from the time.

From January 1 until November 27 of 1999, 940 Cubans were intercepted on the high seas, according to data from the American Coast Guard gathered from the news at the time.

In the fiscal year of 2019 (concluded the last day of September), approximately 454 Cubans attempted to illegally enter the United States by sea, the Coast Guard reported. Sánchez has no doubt that the reason that fewer rafts were intercepted is that the so-called wet foot/dry foot policy is no longer in force. The policy allowed Cubans who managed to touch US ground to remain in the country and condemned those who were detained in the water to be repatriated.

That policy was eliminated by Barack Obama’s administration during the “thaw” with Cuba and is one of the few things that Donald Trump, his successor in the White House, has left in place from that attempt at normalizing relations.

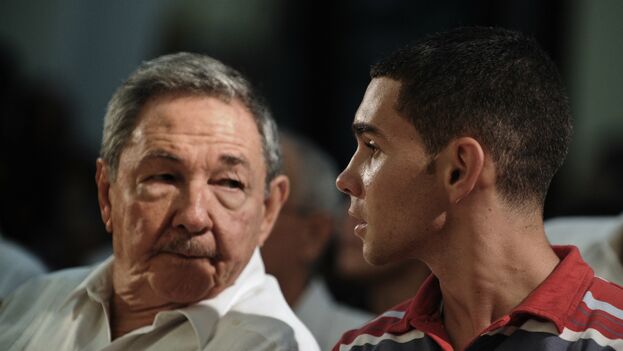

On the Elián raised in Cuba, Sánchez stresses that he was “brainwashed” by “those responsible for his mother’s death” and for that reason he seems “almost an automaton,” always “in a bad mood.”

The most remembered face of the “little rafter” is, however, that of the day on which he was taken from the house of his uncle in Little Havana in Miami by a group of US marshals. The famous photo, taken by the now deceased Alan Díaz, photographer for the American agency AP and winner of a Pulitzer, shows a small 6-year-old Elián in the arms of one of the fishermen who saved him, Donato Dalrymple, terrified in front of the uniformed and helmeted agent with enormous protective glasses pointing a gun at them.

The Elián case, which is seen as one of the many disagreements between the United States and its neighbor Cuba, is, for Sánchez, one chapter more in “the long fight of Cubans for their liberty.”

Translated by: Sheilagh Herrera

___________________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.