![]() 14ymedio, Juan Izquierdo, Havana, 15 February 2023 — As every February 15, official propaganda dusts off its theories about the explosion of the US battleship Maine, sunk in Havana Bay in 1898. After 125 years, the version of the “self-sabotage” of the ship by the US as a pretext for Intervening in Cuba’s war against Spain continues to be taught in Cuban schools and reported in the press as an irrefutable truth.

14ymedio, Juan Izquierdo, Havana, 15 February 2023 — As every February 15, official propaganda dusts off its theories about the explosion of the US battleship Maine, sunk in Havana Bay in 1898. After 125 years, the version of the “self-sabotage” of the ship by the US as a pretext for Intervening in Cuba’s war against Spain continues to be taught in Cuban schools and reported in the press as an irrefutable truth.

Although the “blasting” of the Maine is the cornerstone of the regime’s historiography against the US, none of the investigations carried out in the past have been conclusive about the cause of the explosion. Why does Havana continue to manipulate the facts with such insistence? The response of the official site Cubadebate response is clear: this version is defended because “it sustains the irrational blockade policy,” another ideological symbolic catch-all of the regime.

This Wednesday, in the Communist Party newspaper Granma, officials assert that the battleship was sent as a “steel Trojan horse” to the Island. Knowing “the truth,” however remote it may seem, means winning the “battle of ideas in which this is enshrined to the Cuban people.”

The ship that exploded in the Havana port in February 1898 was a second class military vessel, 324 feet long and 54 feet wide, able to open fire from both sides and with a ram on the bow. Its launching took place on November 18, 1889, but it did not enter service until six years later. The officer who took it to Havana as part of a “friendly visit” in January 1898 was Captain Charles Dwight Sigsbee.

Granma selected and reproduced several telegrams from Captain Sigsbee, the US consul on the island and the US Secretary of State, whose placement suggests that the Maine was not in Havana to protect the citizens of that country present in Cuba, but rather “there was an ulterior purpose”: to produce an “agitation” against the island’s autonomous government – constituted only a few weeks earlier – and to achieve “in all probability” a protest.

From this correspondence, which refers only to the climate of political tension that prevailed at the time, the official State newspaper draws a conclusion: the explosion was caused “by the Yankees themselves” to interfere in “another people’s war,” which was already “virtually won” against Spain by the Cuban Liberation Army.

In the explosion, 254 sailors and six officers died, of the 328 member crew. It was a crew made up of American citizens of German, Swedish, Irish, Norwegian, Danish, and even Russian and Finnish origin. In Cuban schools, however, it is still taught that “the majority of the crew were black” and that the ship’s staff had abandoned them in the bay to die. Cubadebate itself admits that this information is a flagrant lie, although it only acknowledges that it has been disclosed in Cuban education “sometimes.”

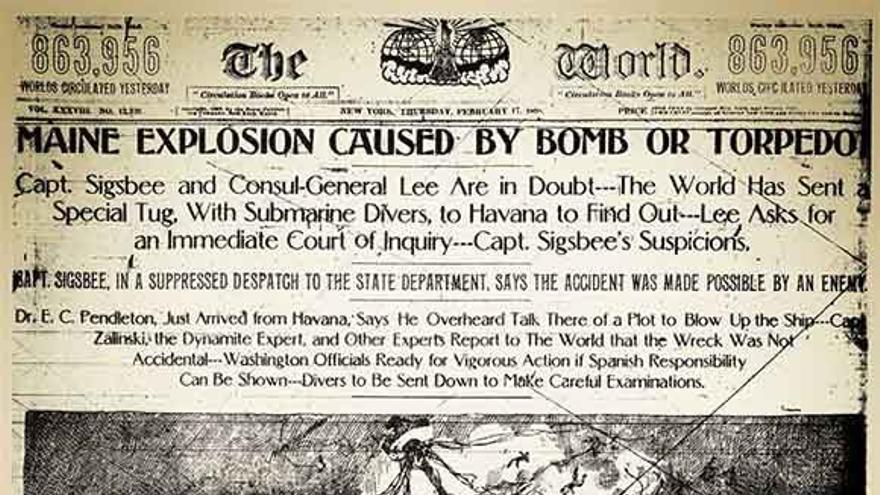

The only truth in the version of events repeated by the regime was the media hysteria that followed the event, the responsibility, to a large extent, of two famous American press magnates at the time: Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst.

With the slogan Remember the Maine – recycled in 1961 by the pro-government singer Carlos Puebla as Remember Girón [referring to (what is called in the US) the Bay of Pigs] – the US newspapers created an unfavorable opinion of Spain among readers, which undoubtedly facilitated the recruitment of young people to participate in the war.

“With the Maine, the independence of Cuba collapsed,” conclude Granma and Cubadebate, also manipulating a few quotes from the book How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed, by US Admiral HG Ricover, without mentioning that this author does not find the “self-sabotage” hypothesis viable either.

The Cuban historian Manuel Moreno Fraginals, in his book Cuba/España, España/Cuba (1995) – one of the most reviled by the regime – affirms that the government of Fidel Castro gave the explosion “the easiest and most convenient interpretation,” in the purest propaganda style of the Cold War, when “in reality there is not a single piece of evidence that leads to such an interpretation.”

“The Americans had plenty of political reasons and internal public opinion to take part in the conflict without resorting to the dangerous extreme of blowing up one of their navy cruisers, killing [more than] 250 marines. The Spanish had even less reason to carry out sabotage of this category. For the Cubans it was almost impossible,” continues Moreno Fraginals.

An updated study on the subject, by the Spanish historian Tomás Pérez Vejo (3 de julio de 1898, el fin del Imperio español , July 3, 1898 / The End of the Spanish Empire, 2020), agrees that the US intervention was going to take place anyway, “regardless of of the causes of the sinking of the Maine .” The problems, he says, were “deeper.”

In addition to all this, the official Cuban press is especially offended by a theory that involves neither the “self-attack” by the US nor an aggression by Spain. It is about the possibility that Cuban insurgents caused the explosion, indignant with the passivity of the United States in the face of the cause of independence, to force the US to intervene.

This hypothesis, collected among others by the classic Cuba: the Struggle for Freedom (1973) by the English historian Hugh Thomas, describes that by 1898, the desire for annexation to the United States was not unheard of among a faction of the rebels. Those who most fervently opposed union with the north were José Martí and Antonio Maceo. Both had died. “Cubans were capable of such an act, as anyone would be after three years of all-out war,” Thomas suggests.

Even a serious naval historian like the Cuban Gustavo Placer Cervera continues to tear his hair out at this possibility. His arguments, however, are not very objective and border on the naive: “Terrorism was not the method of struggle of the Cuban independence fighters,” he affirms. The Cubans did not want to “change ownership” and the US was an “allied country” for the insurgents.

Regardless of the propaganda, Cuban, Spanish and American historians agree that the most likely explanation is an accident. “The Maine blew up because she was carrying a large quantity of the new gunpowder she needed for the heavier guns and which, in its early years, often set off explosions,” Thomas concludes.

The ship remained in the bay until 1911, when the US pulled the wreck and the corpses of the crew out of the water. On March 16 of that year, the Maine was towed several miles from the Havana port and, after several salvo shots to honor the dead Marines, she was sunk again at a depth of more than 1,000 meters.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.