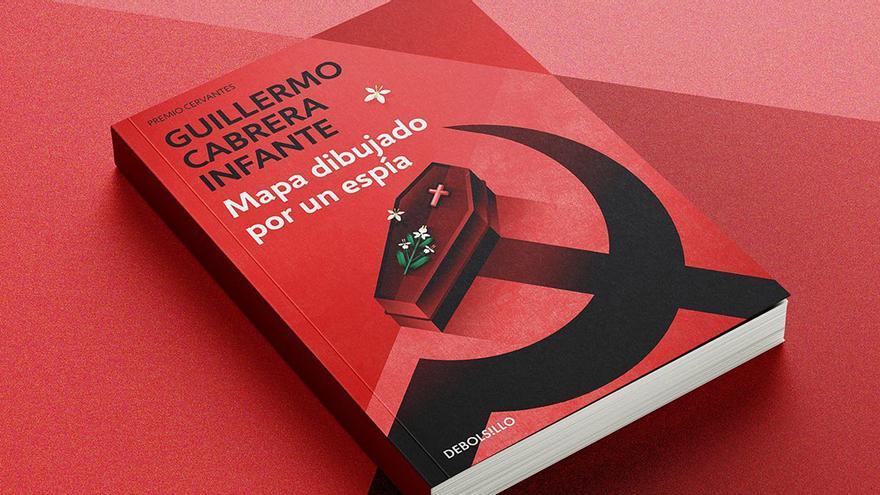

![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 5 June 2022 — The extraordinary and effective Slander Manufacturing Machine is not a single device, but a complex system for organizing informers, informants, police officers, files, compromised neighbors and improvised agents. There is an instruction manual to understand the Machine, but I could never find it in Cuba, when I needed it most: it is the Mapa dibujado por un espía [Map Drawn by a Spy], by Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 5 June 2022 — The extraordinary and effective Slander Manufacturing Machine is not a single device, but a complex system for organizing informers, informants, police officers, files, compromised neighbors and improvised agents. There is an instruction manual to understand the Machine, but I could never find it in Cuba, when I needed it most: it is the Mapa dibujado por un espía [Map Drawn by a Spy], by Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

When Guillermo died, his widow searched her library for lost manuscripts. Hidden in an envelope that the Cuban had sealed and forgotten were the 314 typewritten pages of the Map. From his exile in London — the capital of another island — Cabrera Infante recounted his last trip to Havana, in 1965, and settled scores with the living and the dead.

That year — the story has been told so many times that I no longer know how to distinguish fiction from reality, document from gossip — Cabrera Infante was a cultural attaché in Belgium. There were problems at the embassy and the government sent a mediator. The first job of any mediator is to open their ears and turn the stories and “gossip” into well-written reports. A kind of security policeman called Aldama lived in the embassy, and it was he who started the extraordinary and efficient machine.

Aldama was mixed-race, rather dark, very tall, with a deep voice and tight glasses; he drove a Buick. He had belonged to the clandestine “action groups” against Batista and claimed to know Fidel Castro. He was pleased to refer — as bait to record the interlocutor’s reaction — to an episode of machine guns and thugs in which Castro had been involved.

Far away, in the gloomy and hot State Security offices, Aldama’s information was well received. Thanks to the mediator and to Aldama, the embassy was emptied of the problematic and remaining were only Cabrera Infante and “comrade” Aldama, who began to prowl like a lion of espionage.

Anyone who has read Cabrera Infante knows that there have been few Cubans so sarcastic and moody at the same time. Operating certain threads in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he managed to get rid of the surveillance of Aldama, who was removed from peaceful Brussels back to the sweat of the tropics.

Nobody like a Cuban to be alive and silly at the same time. Little did Cabrera Infante suspect that Aldama was going to drag him down with him — thanks to the slander manufacturing machine — and that the salary would come soon: his mother was about to die and he had to return to Havana.

We are talking about the years in which Castro behaved—he always did—like an agrarian and proletarian czar; in which Manuel Piñeiro, Barbarossa , trained the first State Security agents with the KGB booklet; in which Ramiro Valdés — today a sleeping mummy in an olive-green shroud — was the bloodthirsty Minister of the Interior. Camilo [Cienfuegos] dead; Guevara on a guerrilla tour of Africa; the snitching cederista [CDR member] on his “caramel point.” That was Havana populated by political zombies that Cabrera Infante found.

“I knew,” he said in an interview, “that you couldn’t write in Cuba, but I believed that you could live, vegetate, postpone death, postpone every day. Within a week of returning I knew that not only could I not write in Cuba, I couldn’t live either.

Then begins the story — which is, in effect, a kind of espionage novel in a disfigured country — of the rupture, disenchantment and finally suffocation of the person who is taken off the plane, until further notice, to live for four months in tension and surveillance.

I would have liked to read Map Drawn By a Spy in Cuba, but entering that story while wandering in a similar environment, creating the inevitable links that every reader practices, between fiction and life, between the memory of others and one’s own anguish, would have been little recommended for mental health. I can do it now — read, compare, remember — sheltered by a certain innocence and remoteness.

Everyone who leaves, who thinks of leaving, who dissents, sooner or later acquires a fellow Aldama, a shadow that cuts out the portion of life and country that he has. Until one vanishes, he becomes a non-person, a scourge, a deceased infant. Then he only remains “to flee as far as possible, as fast as he flees from the plague, from the tyrant.”

I close the Map Drawn By a Spy in Cuba, in the nice edition of Galaxia Gutenberg, and make myself a coffee. At a certain point, Cabrera Infante understood that he could no longer return to Cuba alive. All exiles confront that panic. I, who said goodbye to all things — my cat, my books, my places — know that even if I return tomorrow and the Machine no longer exists, there is an irremediable and concrete rupture: everything changes when we are not there, and there is no map that serves to recover time.

The extraordinarily efficient Machine for Making Slander continues its work, perhaps with a little more rust and missing parts, but indifferent after six decades. Cabrera Infante affirms that “when unlivable situations are experienced, there is no other way out than schizophrenia or escape.” I want to think, above pessimism and history, that studying the operation of the Machine is the most lucid way to break it.

When that day comes, we exiles can return home. Although I, who knows my people and know what leg they limp on, I don’t think I’ll come back — as Guillermo would say — on the first plane.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.