![]() EFE (via 14ymedio), Ana Mengotti, Miami, 20 October 20, 2022 — We artists are by definition dissidents of reality,” says Cuban filmmaker Orlando Jiménez Leal, who took the path of exile after Fidel Castro banned his short film PM in 1961, warning those who protested, “against the Revolution nothing.”

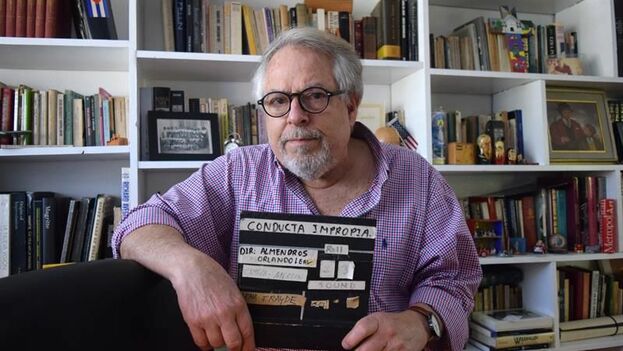

EFE (via 14ymedio), Ana Mengotti, Miami, 20 October 20, 2022 — We artists are by definition dissidents of reality,” says Cuban filmmaker Orlando Jiménez Leal, who took the path of exile after Fidel Castro banned his short film PM in 1961, warning those who protested, “against the Revolution nothing.”

“That was a before and after; it opened our eyes,” says Jiménez Leal, who has been in exile for 61 of his 81 years and will receive an award this Thursday for his career at the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora in Miami.

Jiménez Leal left Cuba on January 2, 1962, and has never returned because, although he admits that he is “curious,” he finds it “embarrassing” to have to ask for permission to enter, he says in an interview with EFE.

When intellectuals asked Castro after the censorship of PM, co-directed by Sabá Cabrera Infante, if there was freedom in Cuba, he replied that “within the Revolution everything, against the Revolution nothing,” recalls the director, who, among other films, directed with León Ichaso El súper [The Super] (1979), a feature film presented and “applauded” at the Venice Film Festival.

The newly created Archive of Cuban Diáspora Cinema, an initiative that emerged at Florida International University (FIU), will give him an award this Thursday for his career.

The founders of the archive, Cuban filmmaker Eliecer Jiménez Almeida and Spanish professor Santiago Juan-Navarro, consider that PM, a short documentary about nightlife in the slums of Havana, is the “zero kilometer” from which Cuban cinema in exile begins.

For Jiménez Leal it’s exactly that: the start of a life outside Cuba with stops in the United States, Puerto Rico and Spain. He has been living in Miami now for nine years.

Although he says that his memory of life in exile is “aged” and the previous one in Cuba, on the contrary, fresh, the filmmaker perfectly remembers his time in Madrid during the final years of Francoism, what he calls “watered-down” Francoism.

At that time he was dedicated to advertising, which was also his livelihood in the United States and the way to finance the films he longed to make.

One of those ads was seen by Julio Iglesias in Puerto Rico and, as he liked it, he contacted Jiménez Leal to direct Me olvidé de vivir [I Forgot to Live] (1980), of which he remembers above all its protagonist, an “charming person” and a “good actor,” capable of improvising.

Previously, he had presented The Super in Venice, which he defines as a “Cuban neorealist film” that “opened the eyes to many who had a fixed idea of the Revolution” by presenting the truncated lives of the exiles in the United States.

Friend of film photography director Néstor Almendros, with whom he directed the documentary on the repression of homosexuals in Cuba, Improper Behavior (1984), and of the writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante, who went into exile like him, Jiménez Leal says that in Cuba they have not been able to “erase him from memory,” and he has become “a ghost that returns.”

Young independent Cuban filmmakers, many of them also outside Cuba, look for his films and declare themselves his admirers, he proudly says.

The authorities don’t mess with him. “As the saying goes, they (those who govern in Cuba) have other fish to fry,” and he mentions “the demonstrators who demand water, electricity and freedom” in the streets of Cuba, and the “imprisoned artists.”

Jiménez Leal no longer makes movies but is still very connected to the cinema and attentive to news on platforms like Netflix, although he confesses that he is, above all, reading books he has already read and watching classic films.

Cinema has changed a lot, especially with the incorporation of digital media. Before, you needed real talent to succeed in cinema; you had to know about technique and industry issues. Now there are more opportunities but there also is a lot of garbage,” he emphasizes.

Over the years, his cinematographic tastes have changed. The “arrogance of youth” made him consider Vittorio De Sica’s Miracle in Milan (1951), a minor film, while at the age of 81 it seems to him a “masterpiece.”

About Blonde, Andrew Dominik’s recently released film about Marilyn Monroe, Jiménez Leal says that it produces “a mixture of feelings” and exhibits the “exceptional” work of Cuban-Spanish actress Ana de Armas.

Among the things he knows he will no longer be able to do is a film that was to be called Cuba Does Not Exist, paraphrasing the exiled Russian writer Vladimir Nabokov, who in an interview proclaimed that “Russia does not exist.”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.