Chile uneasy with success

14ymedio, Mauricio Rojas, Santiago de Chile, 9 September 2016 — Since 2011 the Chilean left has launched a search for “another model,” an alternative to the social market economy that has led the country to remarkable economic and social successes over the last thirty years. Much ink has been spilled on the “inhumanity” of a model that, paradoxically, has lifted millions of Chileans out of poverty and transformed Chile into a middle-class country with the highest per capita income in Latin America.

However, concrete proposals on the make-up of this “other model” were conspicuous by their absence. Earlier, its supporters had bluntly advocated a socialist planned economy as an alternative, but the historical evidence has been responsible for demolishing that option. The closest thing to an alternative is that raised by Fernando Atria and others in the book The Other Model: eliminating private initiative in the areas of welfare services or the sphere of “social rights” (healthcare, education, pensions, housing), as they call them.

This would be a social democratic statist model which is not only an anachronism and has been abandoned by the most modern social democracies of northern Europe, but it is facing a growing repudiation by the Chilean people, as shown by the collapse in the polls of President Michelle Bachelet, whose approval rating is barely 15%, a drop from the 50% at the beginning of her term in March 2014.

This realization doesn’t mean that those of us who defend full respect for the social market economy shouldn’t concern ourselves with its specific forms of operation and its capacity to respond to the always changing demands of the citizens. This is the key in Chile today, where as a result of the free economic model and the tremendous progress already achieved, there are new concerns and demands about the quality, sustainability and, not least, the equity of the progress achieved.

This “uneasiness with success,” that was spectacularly demonstrated in 2011 and was initially channeled by the left, will continue to be present and will determine the Chilean political horizon for a long time. The latest massive demonstrations demanding better pensions and opposed to the system of pensions based on individual capitalization show it very clearly.

This means that those of us who want Chile to continue on its path of success cannot turn a deaf ear to these new concerns and demands, We must make them ours and channel them, but not towards a destructive questioning of the social market economy model, but toward its deepening and improvement.

In the current Chilean case this corresponds, in my view, to putting a clear accent on the social aspect of the social market economy. It doesn’t imply ceasing to question the market, especially considering the strong questioning that day by day does the same and the situations of abuse constantly reiterated. In this sense, I believe there are very interesting viewpoints among British thinkers like Jesse Norman and Phillip Blond, who speak about the need to “moralize the market” in order to make it more efficient and ethically defendable. Leaving aside this issue to concentrate on what, it seems to me, should today be the focal point of a discussion on the social market economy: the social aspect.

Social in this case refers specifically to the need to undertake policy interventions of a redistributive character to correct the spontaneous result of market mechanisms in order to expand the resource base and opportunities available to a significant part of our society. It is, in short, about increasing equality of opportunity and I would like to give three reasons in support of the pressing need for this: the first refers to efficiency, the second to the ethics and the third to policy.

Efficiency

The market is undoubtedly a highly efficient distributor of existing productive resources. However, without corrective intervention may tend to underutilize potential resources, particularly those related to human capital and the talents of the population. We are facing a situation of potential “waste” or “internal brain drain” to use the expression that Sebastian Pinera used in 1976 in one of the essays that formed his doctoral thesis.

This implies that the lack of adequate conditions for its development means that a part of the productive and creative potential of society is never realized and never arrives on “the market” to be efficiently distributed. Clearly, the market creates incentives for the development of the human capital of the population, but its corrective capacity for the “disadvantages of birth” and lack of resources that limit opportunities for many is far from optimal, particularly in countries where large segments of the population lack the minimum conditions to realize their potential and contribute fully to the process of development.

This is obviously the case both in today’s Chile and in Latin America in general, and that is why this point is so important. This is, in short, a huge social waste and, not least, a tragedy for each affected person.

A little history

Economic history abounds with examples that illustrate the key importance of basic equality of opportunities for dynamic and sustainable economic growth over time. The specific content of equal opportunities has varied from era to era and was traditionally strongly related to access to land. Owning land gives the workers the ability to retain for their own benefit an important part of the benefit of its production, which could then be invested in direct productive improvements such as enhancing the education of their children, providing them with increased human capital.

The case of the United States is, in this respect, paradigmatic. The great northern nation achieved world hegemony thanks in large part to the widespread access of immigrants to land, a fact that was decisively reinforced by laws passed during the Civil War known as the Homestead Act, signed by Abraham Lincoln in 1862. This created not only a very stable society of landowners and a large domestic market, but also comparatively optimal conditions for the development of their potential talents. It was the society with the greatest equality of opportunities for its time and therefore also the most prosperous and democratic.

Such examples could easily be multiplied and we would see, almost without exception, that where land was more equally distributed, as in the Scandinavian countries, further progress was generated, and where were the large estates there was, and sometimes still is, poverty. Suffice it to compare, among other cases, the north and south of Italy or Catalonia and the Basque Country with Andalusia and Extremadura in the case of Spain.

This brief reference also tells us something very important about the historical failure of Latin America to achieve development. Large inequalities inherited from the colonial era excluded a large majority of its population from full social participation, thereby burdening the chances to reach, despite the extraordinary export boom of the late nineteenth century, lasting progress.

This is equally important in understanding the history of Chile. By the late nineteenth century the country experienced a spectacular economic boom resulting from the incorporation of the nitrate provinces of Norte Grande. In fact, between 1870 and 1910 there were very few countries whose economic growth exceeded Chile’s. In 1910 it even managed to match or exceed the per capita income of France and Sweden, not to mention Italy or Spain, but this did not lead to Chile to development, but to a frustrating and contentious twentieth century.

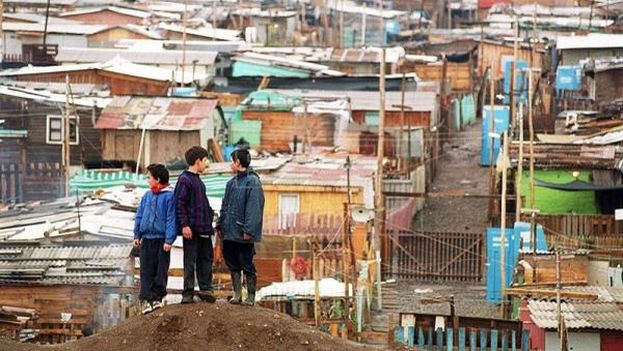

The reason is simple: Chile was a rich country with too much poverty and inequality and it paid dearly for the consequences of this. The manna

from the north, the saltpeter, fell on a deeply unequal society, with its great masses of “pawns,” “farmhands,” “day laborers,” “bums,” or “broken,” who remained prey to poverty, lack of educational possibilities, subordination, exclusion and social and racial contempt.

In the early twentieth century, almost two-thirds of the adult population was illiterate and unable to make a productive contribution that went beyond the basics. Their talent potential was never realized, tying so many Chileans to inherited poverty and condemning the country to underdevelopment. This is the hard lesson for us in our history and it would be very sad were we to stumble again over the same stone.

Ethics

I start from the point of view that efficiency is important, but even more so are the ethical considerations about the need for corrective policy intervention in market mechanisms. From the point of view of the ideas of freedom and equal dignity of human beings, freedom cannot be the privilege of a few, but must be a real right of all. This is the fundamental ethical budget of a free society and will remain so even if a society of free men was not the most efficient alternative in economic terms.

However, the actual exercise of freedom requires conditions that have directly to do with our access to resources and basic security, without which freedom is reduced to a mere empty promise. The freedom to read books is more a mockery than a possibility for those who never had the opportunity to learn to read, freedom of information is reduced to very little when you do not have the minimum training required to process it, and the freedom of movement is nothing more than a travesty when crime takes over our streets or lack of adequate transport facilities make it, in fact, impossible or extremely costly.

In addition, the use of freedom requires, as pointed out by the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, simultaneous access to certain rights, capabilities and resources. Therefore the ethics of freedom coincides with the perspective that emphasizes the importance of basic equality of opportunities.

The capacity and resources necessary to exercise freedom will increase with the advance of progress. It is therefore important not to remain tied to an absolute concept of poverty, but also to consider it from a relative point of view, that is, as that threshold defining the exclusion of social development. This relative poverty that impedes or curtails social participation was rightly emphasized by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations and is the same as that which limits the realization of our abilities or talents. In this sense, real freedom and basic equal opportunities are two absolutely complementary terms that define the ethical view that, in my judgment, should inspire our political efforts.

Politics

The political reasons to put the emphasis on basic equal opportunities seem obvious today. Stability and social cohesion depend on the existence of a widespread sense of justice about the established order. However, the sense of what is right and therefore legitimate has evolved considerably. There was a time when hereditary inequality and hierarchies were considered legitimate, as was the power of absolute monarchs by divine grace or the limitation of freedom or political rights to a minority of the population.

All this is part of the pre-modern social universe, one that was finally subverted by the Declaration of Independence of the United States of 1776 which proclaimed, as founding principles of the legitimacy of the political order, equality as well as the respect for the lives and freedom of all (“all men are created equal … endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights … among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”).

The political history of modernity is about how to get along and to realize these values: equality, not to destroy but to strengthen the freedom, and freedom, so that does not become indifference and a lack of solidarity with others. And that is precisely the great challenge in our Chile at the end of 2014. Only by committing ourselves unambiguously to an equality that extends and strengthens freedom, that is, the basic equality of opportunities, we can successfully fight the socialist idea that seeks to homogenize us, undermine our natural diversity and sow envy.

The political legitimacy of the social order of freedom will only be solid when the overwhelming majority of Chileans feels that they had a fair opportunity to realize their potential and achieve their dreams, and that their children will as well. A just political order cannot rely on the lottery of birth, but on our common responsibility that no one lacks the basic conditions for the exercise of freedom.

In addition, only under those conditions can the greater success and wealth of some be legitimized. That is why in the United States there has been not only acceptance, but even a culture of success and the legitimate enrichment. It is a culture based on the history that has already been discussed, in this equality of opportunities that American society brings to so many and precisely for that reason, allowed it to found the “American dream” on the solid rock of “the land of opportunity.”

In this perspective, it is understood that the current troubling orientation of United States politics with the emergence of populist leaders like Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders is directly linked to the weakening of the “American dream” and the emergence of a broad pessimism in various strata of the US population.

In any case, the historical contrast to what happened in Latin America could not be stronger and more instructive. In our countries, success and fortune are almost always placed under suspicion and it comes from a history of lacerating inequality, where opportunities have been denied to many and where fortune was often built on the basis of violence, with its exponent paradigm in the conquest of America, the connivance with political power, privilege, negotiated or abuse. All this hampers us and urges us to create a more just, and therefore more free, society.

Equal opportunities and State solidarity

Several times I have named the basic concept of equality of opportunity, but without defining it more specifically in our current context. It referred to the historical importance of access to land, but it is clear that today it is no longer about this. In my view, and without detailing each point, it is about these four aspects: education, healthcare, public safety and infrastructure.

It is around these four aspects that we must focus our corrective interventions on the spontaneous effects of the market, committing ourselves to all Chileans have access to those conditions without which the exercise of freedom and the realization of their potentialities become largely illusory.

This does not exclude other interventions, such as those to do with the situation of the greater population, but it centers the discussion on the topic of this essay: a more even distribution of opportunities and the conditions that make them possible.

That should be our great political commitment, but this does not mean at all that we propose a type of welfare state in the style of the current Chilean government, that is, where the State assumes not only the responsibility that no one lacks these resources, but also seeks to monopolize their financing and management. That is something we strongly reject.

Our conception of the welfare state must remain subsidiary to with respect to what civil society can undertake, which should be the focus of our attention. Our interventions must strengthen it, empowering citizens directly and not the State or the politicians. That is the option of solidarity with freedom or, as I have called it in another context, the solidarity State, which is diametrically opposed to State-patron of socialist ideology.

In conclusion, I propose a change in our vocabulary that serves to emphasize strongly the importance we give to the social or solidarity aspect of the market economy. Perhaps we could, instead of the word “social,” which is a little imprecise and overused, use the word “solidarity.” So, instead of a social market economy we could say solidarity market economy.