![]() 14ymedio, Mauricio Rojas, Santiago November 2, 2019 — What happened recently in Chile is not the result of the failure of its development model, but of its success. What has failed is a short-sighted center-right government incapable of managing the profound transformations that model’s success made essential. In short, it is not the model but its defenders who have failed.

14ymedio, Mauricio Rojas, Santiago November 2, 2019 — What happened recently in Chile is not the result of the failure of its development model, but of its success. What has failed is a short-sighted center-right government incapable of managing the profound transformations that model’s success made essential. In short, it is not the model but its defenders who have failed.

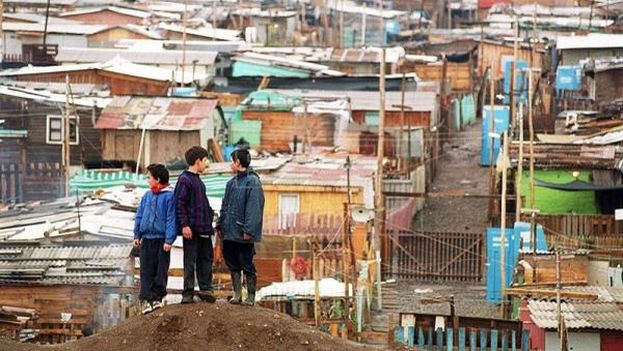

Chile’s progress over the past thirty years has been extraordinary, turning Chile from a fairly mediocre country into the brightest star in the region. It has been, by far, the society with the greatest reduction of poverty, generalized increase in welfare, expansion of higher education, expansion of middle classes and social mobility. Even inequality, although still too high, has been reduced.

According to data provided by Michelle Bachelet’s former finance minister, Rodrigo Valdés, the Gini coefficient fell from 0.573 to 0.477 between 1990 and 2015. In that time the disposable income of the poorest increased much faster than that of the richest (the income of the richest ten percent increased by 208% between 1990 and 2015, while that of the bottom ten percent increased by 439%). continue reading

This extraordinary progress has generated a country totally different from the one that existed thirty years ago. Its social composition and standards of living have changed substantially, but also the ways of perceiving what is just and unjust, what is acceptable and unacceptable, what is dignified and unworthy. This has profoundly altered social demands and what until recently defined the aspirations and common sense of society has become obsolete.

President Sebastián Piñera recently used a well-known phrase spread by Mario Benedetti that synthesized what recently happened to the defenders of the model, and even to some of its detractors: “when we thought we had all the answers, suddenly, all the questions changed”.

However, in this case, these events did not occur right away. It became evident as early as 2011, when new qualitative questions about the justice of society were given old quantitative answers about growth rates or the level of GDP per capita. But this gap between new questions and old answers has become even more evident in recent days.

Basically there was, and still is, a deep misunderstanding about what I called already in 2007 the “malaise of success”, which has to do with what in the 1950s was called the “revolution of rising expectations”. Basically there was, and still is, a deep misunderstanding about what I called already in 2007 the “malaise of success”, which has to do with what in the 1950s was called the “revolution of rising expectations”.

This phenomenon is especially prominent in a country like Chile, which left extreme poverty behind in such a short amount of time, saw the emergence of broad middle classes and experienced an unprecedented educational expansion that multiplied the number of students by ten in the span of three decades.

Such a situation puts the country on its head in the face of the paradox of relative poverty, whereby the feeling of poverty can increase at the same time as poverty is drastically reduced. Absolute poverty is about fighting for the most basic things in life, while relative poverty is about everything one could want but not get, and the latter grows exponentially when we can lift our eyes above the most pressing and our horizons are broadened by greater access to education and the media. Frustration and discontent can grow despite our progress, not least when others enjoy what we lack.

At the same time, there is growing anguish at the possibility of losing the social gains recently won, thus giving rise to what the German sociologist Ulrich Beck called a “risk society” (Risikogesellschaft), dominated by the feeling of insecurity and precariousness in the face of an endless number of contingencies that may threaten the foundations of our lives.

Meanwhile, to the extent that the most basic needs are satisfied, there is, especially among young people, a shift in priorities. According to the concepts that Ronald Inglehart coined to understand the European youth revolt of 1968, as welfare increases societies move from “materialistic values”, characteristic of the hard struggle for subsistence, to “post-materialistic values”, where preferences tend to be directed towards “a good life” and personal self-realization. In this way the material conquests previously reached are devalued, or even despised, in order to orient themselves towards the search for a different society, defined as more human, collaborative, altruistic and egalitarian.

Therefore, it represents a confluence of situations and demands of a very varied nature, which in a given moment – the one we are living now, for example – combine to create what Ernesto Laclau has called, in his book on Populist Reason, an “equivalential chain” of discontents and negations, where the repudiation of a series of very dissimilar situations unites and makes a very broad and diverse spectrum of rejection and change wills equivalent. There is no common social project, but there is a common rejection, and it is precisely this that creates the conditions that, added to a “void of representation” on the part of the existing political elites, make a chaotic and open moment such as the one we are experiencing possible.

The emergence of this broad and multifaceted rejection of something diffuse that some call “the (neoliberal) model” or, to put it more concretely, a society of abuse, injustice and insecurity, is the paradoxical result of the progress gained when it coincides with the failure of its defenders to understand the new demands that arise from that progress and to propose, in a vigorous manner, the reforms necessary to structure a new social pact that is equal to the development achieved, especially in terms of inclusion, equity, the fight against abuses, equality of opportunities and solidarity.

As the current government testifies, it is not that some valuable efforts have not been made in that direction, but they have clearly been insufficient. The prolongation of a series of “social emergencies” – such as the generally miserable level of pensions, the high pharmaceutical costs or the brutal impact of “catastrophic diseases” — of blatant abuses — such as automatic TAG (automated toll) hikes or other motorway tolls — or violent price hikes for basic services — such as electricity or transport — have been fatal.

But then there are the more fundamental shortcomings, such as those affecting public health or education, and, more generally, the lack of a social safety net to ensure a minimum of dignity and a safeguard against unforeseen events, especially in view of the neglected demands of the new middle classes.

The dogmatic defense of the current tax rates, particularly for the wealthiest and most income earning sectors, has been a key impediment to progress in this direction. However, so has the anachronistic fixation on a social policy focused on the Chicago School, that is to say, that only points to the needs of the poorest.

Ignoring the need to build a modern welfare state, that is, without monopolies and that combines significant levels of redistribution and equality of opportunities with citizen empowerment and freedom of choice and enterprise in the areas of welfare guaranteed for all citizens (as in the case of countries such as Sweden), has been nefarious.

Today we are faced with such a crisis of legitimacy of the prevailing system that the doors are opened to raise, and even accept, all kinds of nonsense, such as chavista assemblyism, plebiscite democracy, public monopolies or fiscal indiscipline.

Today’s panic is spreading among many who did not know how to defend the model of development that has brought us so much progress, instead reforming it in due time and attending to social urgencies in a forceful way.

When the doors to evolution are closed, they can be opened to revolution and disorder. As Arturo Alessandri so often said, it is necessary to advance “without hesitation along the paths of evolution to avoid revolution and upheaval.” This should be the greatest lesson of these dark days.

Mauricio Rojas is a researcher at the Department of Economics and Business of the Universidad del Desarrollo, in Santiago de Chile, and a Senior Fellow of the Fundación para el Progreso.

Translated by: Rafael Osorio

__________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. You can help crowdfund a current project to develop an in depth multimedia report on dengue fever in Cuba; the goal is modest, only $2,000. Even small donations by a lot of people will add up fast. Thank you!