The sweat of the three women who put me into a police car still sticks to my skin and in my nostrils. Huge, hulking, ruthless, they took me into a windowless room where the broken fan only blew air towards them. One looked at me with particular scorn. Maybe my face reminded her of someone in her past: an adversary in school, a despotic mother, a lost lover. I don’t know. What I do remember is that, on the evening of October 5, her look wanted to destroy me. She was the one who ferreted around under my skirt with great delight, while two other uniformed policewomen grabbed me for the “search.” Rather than seeking out some hidden object, the purpose of this search was to make me feel violated, defenseless, raped.

Every six hours they changed my guards. On the midnight shift they were noticeably less strict, but I locked myself in my silence and never responded to their questions. I evaded myself. I chose to tell myself, “They’ve taken everything, even the clip that holds my hair, but — ridiculous searchers — they have not been able to take from me my inner world.” Thus I decide to take refuge, during the long hours of my illegal confinement, in the only thing I had: my memories. The room wanted to appear neat and clean, but everything had its share of filth or breakage. The granite floor tiles were covered with a good dose of accumulated grime. I stared at the figures made by the little pebbles cast in each tile and the gobs of dirt. After a while faces jumped out of this constellation. Characters flourished in the rough floor of my cell in the police station in Bayamo.

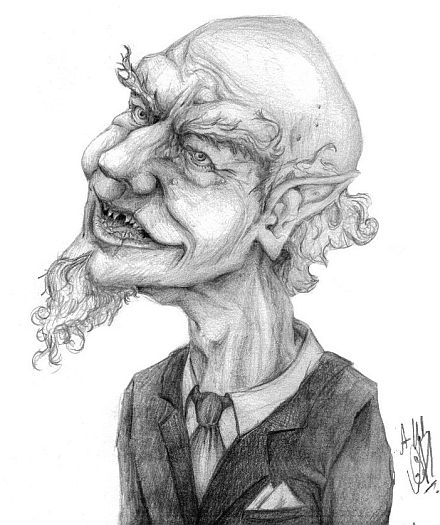

Springing from there was the lanky countenance of Don Quixote, while in that corner I could see the simple profile of Eduardo Abela’s “Bobo” — that wise fool who mocked the Machado dictatorship. Some oblique eyes, shaped by mortar and gravel, looked incredibly like the protagonist in the film Avatar. I laughed and my perennial watchers began to believe that my refusal of food and water was literally frying my brain. I espied, in the irregular granite, the Hunchback of Notre Dame and the slender figure of Gandalf, staff and all. But standing out among all these forms that emerged from the rough paving there was one — the most intense — that seemed to cavort and laugh before my eyes. Perhaps it was the effect of thirst and hunger, the truth is I don’t know. A long-bearded dwarf with a cynical look, slyly mocking.

It was Rumplestiltskin, the star of a children’s story where the queen is forced to guess his complicated name and if she does not she must give the despotic elf her most precious possession: her own son. What was this character doing in the midst of my temporary imprisonment? Why did I see him over so many other visual references I have accumulated in my life? I immediately intuited the answer. “You are Rumplestiltskin,” I said out loud and the gorgons watching me looked worried. “You are Rumplestiltskin,” I repeated, “and I know your name. You are like dictatorships, and once we start calling them by their name, it begins to destroy them.”

6 October 2012