![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 17 December 2023 – It is much easier for a boy to be friends with his grandfather than with his father. The older one understands you, he has time on his hands once again, he plays – dominoes, chess, cards – and he rereads the books he bought when he was a young man. An old man is just a boy, with ailments. A father shapes his son’s character through opposition, making war with him; a grandfather does it through being close to him, and by giving advice. The father is master of his time, he calculates it, knows how to use it well and how to dominate it. For the boy and his grandfather time does not exist. One is entering into life, the other is exiting. That’s why they play together.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 17 December 2023 – It is much easier for a boy to be friends with his grandfather than with his father. The older one understands you, he has time on his hands once again, he plays – dominoes, chess, cards – and he rereads the books he bought when he was a young man. An old man is just a boy, with ailments. A father shapes his son’s character through opposition, making war with him; a grandfather does it through being close to him, and by giving advice. The father is master of his time, he calculates it, knows how to use it well and how to dominate it. For the boy and his grandfather time does not exist. One is entering into life, the other is exiting. That’s why they play together.

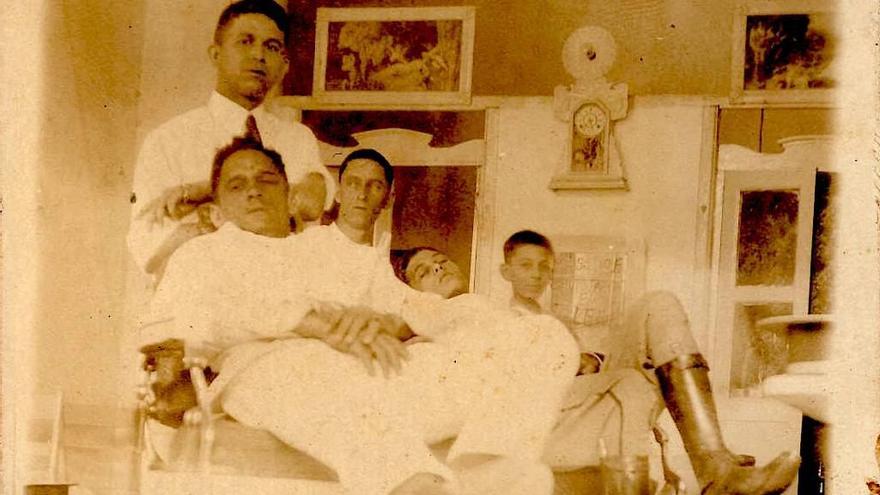

My maternal grandfather was a barber and a musician; my paternal one was a pharmacist. These humble professions are often present in the books that I have written, they are ’of the people’. I would have liked also to have had for a grandfather a scissor-sharpener, an aviator or a ship’s captain, or a mortuary photographer – there were plenty of those on the island – or an antiquarian. Nevertheless, life was generous enough in offering me three worlds: those of barbers, chemists and municipal bands.

In 1944, when my great grandfather got married, he had already been working as a barber for years. I know the reason why, in the newspaper which announced the wedding – I still have the cutting – the newspaper’s delivery man wrote the word “barbershop” next to his name in impeccable calligraphy and took the trouble of highlighting the announcement in blue ink. (The best news of the day, I have to say, because the rest of the paper is dedicated to describing developments in the Second World War, and to asking the youth of the town to report to the recruitment committee and march on Europe).

In 1944, when my great grandfather got married, he had already been working as a barber for years

As soon as his son could manage a comb and a pair of scissors, he too took up the trade. I look at him now, formal, concentrated, white shirt and beige trousers. The photo, I estimate, is from the mid-sixties and it wasn’t long before he himself was called up for military service. Seated, and covered in a sheet, there is a man having a razor haircut. The locks are falling into his lap. A Guajiran man behind him leaves his own chair to check on the younger man’s handiwork. No one speaks, perhaps because of the presence of the camera. There’s a certain tenderness in the way in which the photo is taken. Translucent and ochre, the image feels more like a memory than a print. I’ve always thought that the person behind the camera lens must be my grandfather, proud of his new recruit.

In my village there was a detailed inventory of barbers, pharmacists and everything else. “At first the barbers practised like dentists”, remembers a writer in 1943. In the “1800’s”, he adds, one black man called Juan Rojo had arrived with his razor blades and shaving cream, and later on a Spaniard called Bruno Claraco, and it wasn’t long before the appearance of “Delfín Miranda, who had no qualification, and Delfín Barrena, who did have one”.

I don’t know when my great grandfather arrived but I do remember his last barber shop, the one he left to his son. There was a Koken swivel-chair – which later, after the death of the old man, made me sad, seeing it in the hands of another barber. It was in a bright and white room with a big mirror fixed to a structure that was fitted with little drawers. I’ll never forget the buzz of his electric clippers as it ploughed its way through grey hair and curls, and fleeces and manes and emerging bald patches and mops. Head shaving has always had something of a cleansing ritual about it: one attends the barbershop like one goes to confession or visits the doctor. One pays dearly for being unfaithful: the barber will always be able to detect someone else’s handiwork and knows how to punish an infidelity by leaving a “cockroach”, or one sideburn longer than the other.

Where the barbershop was all party-like, all cigarette smoke and conversation, then the pharmacy was all severity, and mystery

A barbershop is full of stories. Whilst my grandfather was describing how to shave the head of a priest – you put a circular cap over the crown, mark the tonsure with the razor and shave round the bald patch – it wasn’t considered wrong to interrupt him in order to look out of the window if a woman who looked a bit like Sofia Loren or Kim Novak (and knew how to move like them) happened to be walking by. They were different times, less toilsome ones.

Where the barbershop was all party-like, all cigarette smoke and conversation, then the pharmacy was all severity, and mystery. In another photograph – there’s no limit to my archives – my paternal grandfather manipulates his test tubes and his pestle and mortar. At that time, pharmacies were a paradise of coded names, powders and resins that one always took to be poisons. The shelves were full of porcelain jars, with names marked in indigo blue ink: agrimonia, phecula patata, folium eucaliptus, angelica, dens leonis. Chemists, and my grandfather was no exception, kept recipes for numerous unguents in a book with black covers. A book which was inaccessible to me, like any grandfather’s things, right up until he died.

Both worlds – no need to mention the band: music needs no explanation – have so much connection to writing, which only now, far away from the ghosts of that village, do I actually realise. Barber or pharmacist, both have to cut, clear, mix, find the right measure, make poisons or conjure up balsams. In any event, the occupations of each of those old men are not forgotten.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.