The current state of Cuba confirms the impossibility of social progress without civic participation of citizens. The structural crisis in which we are immersed and the obstacles to overcome it, are closely related to the absence of popular participation as a dependent of history. A reality exacerbated by the fact that our country, in terms of freedoms, has receded to the point where it was in 1878. Therefore, changes in the economy are as unavoidable as changes in human rights to promote civic participation from civil society in the decisions of the nation.

The current state of Cuba confirms the impossibility of social progress without civic participation of citizens. The structural crisis in which we are immersed and the obstacles to overcome it, are closely related to the absence of popular participation as a dependent of history. A reality exacerbated by the fact that our country, in terms of freedoms, has receded to the point where it was in 1878. Therefore, changes in the economy are as unavoidable as changes in human rights to promote civic participation from civil society in the decisions of the nation.

The importance of the political — the scope of social reality referred to the problems of power — is that it provides a vehicle to move from the desired to the feasible and from the feasible to reality, an area that implies the State as much as society. The attempts towards progress that ignore this truth, as has happened so far, are illusory.

The relationship between what is happening right now in our country with the public reappearance of the ex-chief of the Cuban State — phenomenon which is unsustainable in the short-term for the ungovernability that it generates — has as a common denominator with previous eras of Cuba the absence of the Cuban as a historical subject. To demonstrate that continuity, I will take this opportunity to look at the first attempt in Cuba of a presidential re-election bid.

The 1901 Constitution, in Article 96, referring to the duration of the presidential term, said that the office will last four years, and no one may be president in three consecutive terms. Therefore the conflict over the re-election bid in 1906 is not in the illegality, but in something else.

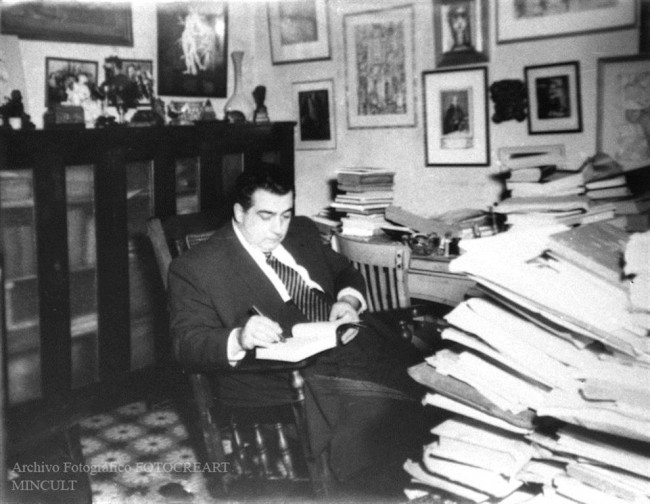

Tomás Estrada Palma (1835-1908), joined the Ten Years War from the beginning, where he received the rank of General. In the Government of the Republic in Arms he served as Secretary of War, of Foreign Affairs and President. In 1877 he was taken prisoner and released after the Zanjón Peace. He emigrated to the United States, where he founded a school for Latin Americans. In 1895 he was appointed minister plenipotentiary of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Cuba in the U.S. and was the center of the Revolutionary Council in New York. In 1901 he was elected President of the Republic of Cuba.

Estrada Palma concentrated in an important enterprise, the austerity in the management of public assets. However, while he considered that the people had no training for living in freedom, he did not endeavor to strengthen the spaces and institutions to achieve it. That decision, conscious or not, is a manifestation of Messianism, a pious hope in the ability of an earthly being to lead a people to salvation. In the absence of the general public, his administration was limited to a political elite devoid of civic culture. For example, the enactment of laws became very difficult because for approval it required the presence of two-thirds of the congressmen, whose attendance, since it was not mandatory, was exploited by political parties (Liberal and Moderate) to hinder the work of legislation in their struggle for dominance in Congress. In this situation, President Estrada Palma, who had refused to join any of the existing parties, decided to join the Moderate Party, to try, together with the work of the Executive Branch, to obtain a quorum and to enact laws and necessary measures.

With regards to the theme of re-election, Estrada Palma created the War Cabinet to guarantee victory and get a majority in the Senate and the House; he pushed it to use all governmental force, including the use of violence and fraud against the Liberal Party, which responded with the abstention, and consistent with our culture of intransigence and machete, took up arms. A process that caused heavy damage and loss of life before and during the conflict, among them the killing of Colonel Enrique Villuendas in Cienfuegos and General Quintin Banderas in Havana, whom I shall address in my next article.

The rebels, in a manifesto dated September 1, 1906, proposed, inter alia, the cessation of hostilities, the restoration of peace, freedom for those detained or prosecuted for activities related to elections and declaring vacant the positions of president and vice president of the republic, provincial governor and provincial council, covered in the last election period. Estrada Palma for his part required them to lay down their weapons first and then talk. The intransigence of the parties and accordingly the failure of the mediation of a group of veterans, among whom were the generals Bartolome Maso, Mario García Menocal and Cebreco Augustine, who rose to confirm the office of president and cancel the rest of the elected offices.

The intransigence led to the outcome. Between 8 and 12 September, Estrada Palma suspended the guarantee, requested the sending of warships and intervention; a request that the U.S. president himself considered inappropriate. According to Hortensia Pichardo, Theodore Roosevelt exhausted all available means to avoid that step. Among these the media quoted his letter to Gonzalo de Quesada, 14 September 1906 and his telegram to Estrada Palma, on the 25th of the same month. In the first, Roosevelt reveals, among other arguments, that:

“Our intervention in Cuban affairs will be realized only if it is shown that Cuba has fallen into the habit of insurrection and lacks the necessary control over herself to realize peaceful self-government, and so that its rival factions have plunged into anarchy.”

In a letter to his friend Teodoro Pérez Tamayo, dated October 10, 1906, Estrada Palma argues that the settlement through the pact with the rebels was the worst thing that could have been thought of, as the secondary problems that would arise later — so many and so difficult to solve — weakening, of not losing, the moral force of legitimate power and no authority other than the settlement of disputes, which I repeat would be so many and so difficult, these problems, which would lead to the country being kept for many months amid constant agitation, as pernicious as the effects of the war itself. So, he says, he decided to irrevocably resign the Presidency, to completely abandon public life and look within his family for a safe haven from many disappointments. His ultimate sacrifice, in his words, to make it impossible that the Government should fall into criminal hands. A decision that led him to notify the Government of Washington:

… “of he true situation in the country, and the lack of measures by my Government to provide protection to property, considering that the time had come for the United States made use of the right conferred by the Platt Amendment. So it did” …

For these reasons, on September 28, together with the Vice President and the secretaries, he submitted his resignation to Congress and the country came under a provisional government headed by the Secretary of War the United States, William H. Taft, which constituted the second American intervention in Cuba.

The lack of civic culture, the absence of the citizenry in the decisions regarding the destiny of the nation, the tendency to violent solutions and Messianism, demonstrated itself in the work of the Cuban political elite. A portrait put forth magisterially by Carlos Loveira in his republic of “General and Doctors. ”

According to Hortensia Pichardo, the first Cuban republic had been killed by its own children. I would say that at the hands of a handful of its children, because the vast majority, as in other political events, was absent from those decisions. The teaching of this episode in our history, and of others we attempt, indicates that the preparation for political participation is a long and difficult, but much safer than we have traveled so far, where the majority of Cubans have very little to do with what is happening.

Translated by uncledavid

August 2 2010

In late November, a kind reader wrote to me suggesting I prepare a list of all dissident groups and political parties on the Island. Since the proposal has appeared publicly in the comments on more than one occasion, I propose –in turn- to answer publicly and take the opportunity to share some impressions, given that other Cuban friends inside and outside the country have shown interest in the subject.

In late November, a kind reader wrote to me suggesting I prepare a list of all dissident groups and political parties on the Island. Since the proposal has appeared publicly in the comments on more than one occasion, I propose –in turn- to answer publicly and take the opportunity to share some impressions, given that other Cuban friends inside and outside the country have shown interest in the subject.