Jose Lezama Lima (1910-1976) is not gone. This is the feeling you get when you visit the museum of the master of Cuban prose in Trocadero street, in central Havana.

You don’t need to be supernatural to sense the weary, asthmatic breathing of the fat Lezama while you pass through the halls of this house, residence of one of the greatest authors of this green island.

The Cuban intellectual was born on December 19, 1910. And like nearly all the geniuses, he was misunderstood in his time. His father, Jose Lezama Rodda, of Basque heritage, founded, and eventually lost, a sugar business in Cuba.

Rosa Lima Rosado, his mother, formed part of a family of independent thought. At the end of the 19th century, she felt obligated to leave the island. she knew and collaborated with the national hero of Cuba, Jose Marti, in his exile in Florida.

Lezama Lima had two sisters, Rosa and Eloisa, who both died early in their lives. From when he was a boy, like every good Habanero, he played baseball and caused trouble with his friends from the neighborhood. He was an infielder, and had pretty good hands.

But one day when he was an adolescent, his friends went to find him for game, and Lezama told them “I’m not coming out today, I’m going to stay in and read.” He had started reading Plato’s Symposium. He was fifteen years old, and since he was eight he was a voracious reader of Salgari and Dumas, Cervantes and his Quixote.

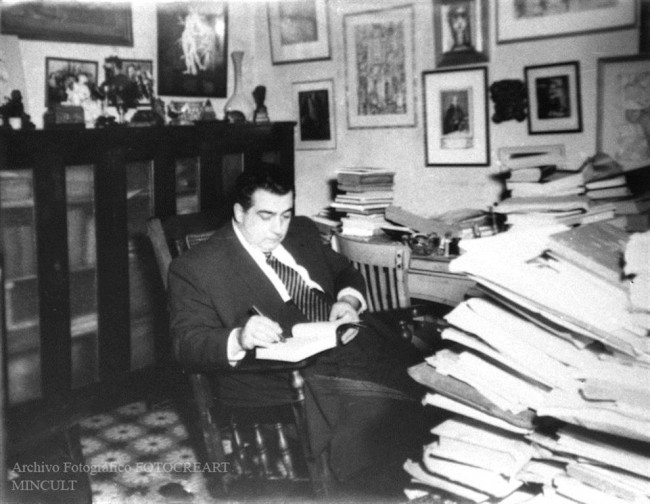

He became a lawyer, and began to work in a simple post of the secretary of the Superior Counsel of Social Defense, in the jail of the Castillo del Príncipe, the main jail in Havana. And from this date forward, he was a great man of letters.

In 1937, his collection of poetry The Death of Narciso, was published, which was written in 1931. In his day, another giant, Cintio Vitier, affirmed: “All the poetry of Mariano Brull, Emililo Ballagas, Eugenio Florti, like witches riding brooms, flew out the window when I read ‘Danae wrote about the golden time by the Nile,’ the first verse of the Death of Narciso. Cuban poetry changed overnight.”

Later, he began to circulate in cultural reviews of high esteem, edited in Cuba in the decade of 1940-1950. It was in Origins, perhaps, where Lezama Lima made his impression as a writer.

In 1959, el comandante Fidel Castro arrived, along with his hurricane of radical reforms. So much machismo and testosterone; the caudillo style and an Olympian disdain for the free thinkers, caused more than a problem for the massive Jose Lezama.

Despite being married since 1964 to Maria Luisa Bautista, a noted literature professor, the fat Lezama was a closet gay. We already know how the Castro government treated homosexuals in this time.

They were turbulent times. Whoever had different sexual orientations was sent to prison or to a type of concentration camp called UMAPs (Military Units in Support of Production). And even though Lezama never received a punishment that severe, he suffered. The greatest scandal arrived in 1966.

The name of the scandal was the supreme novel of Cuban literature: Paradiso. It had a limited edition. It put in check the iron censorship of the state, that always held literature suspect, bourgeoisie, and counterrevolutionary. The sexual adventures of Jose Cemi disquieted the Criollo hierarchy, who saw in the gays, and sodomy, a latent danger to the concept of the New Man, dreamed up by Che.

In spite of everything, the Maestro never wanted to abandon his country. In Cuba he found his muse. His house on Trocadero was his heart, he came to say. And there he shut himself in amongst his writings. Tightly.

Difficult years. The economic shortages affected the population. And Lezama, an incurable luxurophile, suffered from royal hunger. He made up for it, and then some, whenever a friend invited him to dinner. It was said that at receptions in Western embassies, on certain nights of ferocious appetite, Lezama devoured an army of croquettes and canapes.

He died in 1976, his fame faded due to censorship and official acknowledgment of a low profile. They then turned him into an exquisite cadaver. A common thing for Fidel Castro’s government with critical intellectual figures or those with little loyalty to the regime. Once they’re buried, of course.

The big guy who would have been one hundred this year died in house No. 162 on Trocadero Street. His thick anatomy permeates the house turned into a museum. If you feel, as you tour the grounds, the coughing and asthmatic wheezing of the Master, don’t be frightened. It is Lezama who would like to greet you.

December 16, 2010