Having just got his hands on the hard disk in its protective case, he mentally reviews his fixed clients whom he will have to alert. It’s a kind of reflex conditioned by the rush to make money. But all that later. Now, the first thing is to pay the bus driver who carried this portable hard drive from Havana to the other end of the country, with a treasure consisting of many gigabytes of information.

Having just got his hands on the hard disk in its protective case, he mentally reviews his fixed clients whom he will have to alert. It’s a kind of reflex conditioned by the rush to make money. But all that later. Now, the first thing is to pay the bus driver who carried this portable hard drive from Havana to the other end of the country, with a treasure consisting of many gigabytes of information.

Three convertible pesos to the driver (75 Cuban pesos), as thanks for his reliability. On the other end of the Island, from the west, his business partner brings the device to the bus station every week and there he contacts the driver whose turn it will be the transport the goods this time. He gives him the contact details of who will collect the package, and as a precaution notes the license plate of the bus and the driver’s name. The same procedure is followed at the other end to send it back to the capital.

Now he slips the device into his backpack, and rides his bike through the deserted streets of the city.

What’s he looking for? Perhaps a secure telephone from where he can alert his customers, “The package arrived, will you take it now?” But before starting the transaction he has to be sure the merchandise is of perfect quality and complete. He pedals home, connects the hard disk, and verifies, yes, the 110 gigabytes are there, in a file with the date of the last week.

Then he does a superficial check — he doesn’t have time to watch everything — to make sure the quality of the video is good, or acceptable. No one wants to pay if they can’t see it well.

Finally, the contacts. He goes from house to house, connecting the hard disc, copying the designated folder, and pasting it in the space the client assigns for it. Never less than 100 gigabytes, never more than 120. That’s the average.

What is contained in that device, which occupies so much digital space and that is so tremendously in demand by society? Information of various kinds. One of the most acute scarcities for Cubans anchored on their floating Island of Silence.

The same news from America TV and Mega with TV shows in high demand among the Hispanic community in the United States. From football games broadcast live by ESPN, to the chapters of specialty Mexican soap operas on Univision. New films, documentaries from the Discovery Channel, musical concerts of some star — especially anything Latino — appearing on glamorous world stages.

In total, 110 gigabytes can capture a week of cable television, and for 4 convertible pesos it’s downloaded to the personal computer of a Cuban who otherwise would never have access to this multimedia diversity.

In some of the more affluent cities in Cuba, these weekly packets cost 10 convertible pesos. In others, especially in the east where less money flows, they vary between 4 and 6. It depends on the place and the provider.

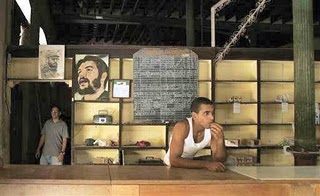

How do the local distributors get this mass of information and entertainment into specific hands? Through semi-suicidal risks, primarily in the capital, where they install a satellite dish on their roof and make offerings to the Orishas that none of the neighbors will decide to inform the police about this serious violation of law.

The antennas, like artifacts of war, are hidden with every kind of trick: a leafy grape-vine, a cement overhang, sometimes painting it so it blends in with a background of the same color. Ingenuity is never lacking in Cubans in their eternal effort to survive.

These parabolic kamikazes expose themselves to exorbitant fines and much more serious penalties (they can lose their homes or even end up in prison if they are repeat offenders). They record all the programs of popular interest on their computers. And sell the packages to street distributors throughout the country.

Thanks to such methods they can read the independent blogs in Cuba, the incendiary texts that appear on the web, daily publications like the Nuevo Herald or the BBC. A person privileged to have Internet access — legally through their work, or illegally installed in their house through the black market — downloads the articles and distributes them to his acquaintances free through the miracle of flash memory. Sometimes they charge for it. Otherwise they do it out of basic solidarity.

But one thing I am sure of: I do not believe these renovated pirates of the Caribbean, Creole pirates who make a living smuggling gigabytes and copyrights, are aware of how much their commercial efforts form a part of a Cuban democratization that must begin with one basic element, access to information.

Behind its censurable illegality — looking at if from the viewpoint of international standards of respect for intellectual property — lies a blunt reality that is not too hard to elucidate: there is no worse enemy to the Cuban regime in its more than half a century of existence than technology. There has been no enemy more mortal, subversive and uncontrollable than the Internet.

This is an army — of flash memories, of computers armed with bits and pieces, of DVD players which until very recently were also illegal — that has destroyed a deep isolation suffered by a country disconnected from the planet. And it is a proven fact that against this army the totalitarian regimes of today do not know how to, and cannot, fight.

Thanks to piracy, Cubans today know that beyond the water that encircles them lies another distinct world the TV informs them of. Thanks to contraband music, newly-released movies, audiovisuals with other ways of looking at reality, they have discovered, bit by bit, timidly, the real reasons why they are not allowed to travel.

It would not surprise me if — like the Beatles were banned from the national scene in the past — today the Spanish series Travelers’ Streets, with its globe-trotting journalists and a fanatic clandestine audience in my country, would be declared material non grata by any establishment in Revolutionary lands.

To my friends, the pirates of my Island country, let me say that unfortunately I am not yet an author of any work whose rights are worthy of being violated. But I aspire to be one. If, sometime, a single word of mine, the smallest bit that comes from my keyboard, is worthy of being downloaded from the Internet, plundered by publishers or legal commitments, or in some way is distributed by the brothers of my muted land, don’t ask my public approval, because I would not be able to give it.

But cynically I say to you: Know that internally I support you, with the same conviction and vehemence with which I turned over, in the past, four convertible pesos for a small breath of freedom. Because the real crime is not piracy. The real crime is disinformation.

January 15 2011

Having just got his hands on the hard disk in its protective case, he mentally reviews his fixed clients whom he will have to alert. It’s a kind of reflex conditioned by the rush to make money. But all that later. Now, the first thing is to pay the bus driver who carried this portable hard drive from Havana to the other end of the country, with a treasure consisting of many gigabytes of information.

Having just got his hands on the hard disk in its protective case, he mentally reviews his fixed clients whom he will have to alert. It’s a kind of reflex conditioned by the rush to make money. But all that later. Now, the first thing is to pay the bus driver who carried this portable hard drive from Havana to the other end of the country, with a treasure consisting of many gigabytes of information.

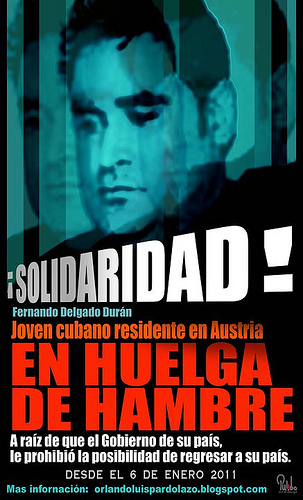

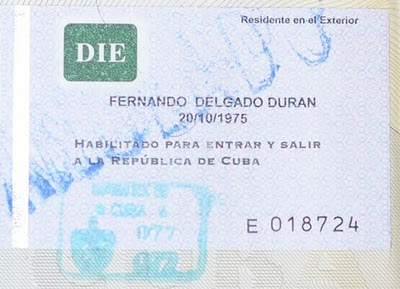

The year 2011 has begun and Cuba continues to be prey to a dilemma; a government of more than half a century, led by the same old men, who have given themselves another opportunity to correct their mistakes before leaving this world. So the president of the State Council, Raul Castro, expressed in his most recent speech.

The year 2011 has begun and Cuba continues to be prey to a dilemma; a government of more than half a century, led by the same old men, who have given themselves another opportunity to correct their mistakes before leaving this world. So the president of the State Council, Raul Castro, expressed in his most recent speech.