When, three years ago, Octavio, 52, asked a relative in Miami for a loan of $ 8,000 for the purpose of opening a ’paladar’ (private restaurant) in the Havana neighborhood of La Vibora, he was sure that his business would prosper. Not so. In this false Cuban winter, he still owes $8,000 to his relative. And even worse, he had to close the restaurant due to unprofitability.

When, three years ago, Octavio, 52, asked a relative in Miami for a loan of $ 8,000 for the purpose of opening a ’paladar’ (private restaurant) in the Havana neighborhood of La Vibora, he was sure that his business would prosper. Not so. In this false Cuban winter, he still owes $8,000 to his relative. And even worse, he had to close the restaurant due to unprofitability.

“In addition to having just a few customers, purchasing fresh, quality food was an ordeal. For these businesses to work you have to have good contacts in the black market. Buying food and supplies legally doesn’t work, you can’t progress. Not to mention that there is no wholesale market and the taxes are very high,” he says.

To fail at a private venture is disappointing. Of course in real capitalism there are winners and losers. But the Cuba of Fidel Castro was always considered an anti-capitalist sanctuary and enemy of the free market.

When in 1993 the Castro government authorized the opening of farmers markets and handicraft workshops, it was under a strict fiscal control and the jealous supervision of a battalion of state inspectors who, because of the rules and prohibitions imposed on self-employment, found it very easy to catch the owner in violation of the laws drawn.

Over time, the private work languished, suffocated by a raft of measures that prevented it from thriving. In October 2010 General Raul Castro reopened the private sector and relaxed the rules.

It was logical. The olive-green autocracy wanted clear out the public accounts and payrolls inflated with unproductive workers and employees who were quite heavy a burden. The regime’s plan was to layoff a million and a half workers in three years. To fend for themselves, setting up timbiriches — tiny businesses — selling croquettes or refilling cigarette lighters.

So quietly, without the sound of revolutionary marches, erasing the official discourse of “Fatherland or Death We Shall Overcome” and sticking out its tongue at Marxist rhetoric, the Castro government morphed from a socialist system (at least as we read in the Constitution) a formidable apparatus of state capitalism, corporations run by anonymous military men in white guayabera.

For a ton of Cubans, accustomed to 54 years on chanting slogans and cheering, waiting for orders from above and receiving meager subsidies, it was traumatic to be told from the podium that they should change their mentality.

Of the more than 450,000 private workers licensed to practice on their own, many had been doing it for a while clandestinely. Upon opening the door of a disguised capitalism, those who were caught naked were precisely those who worked for the state. They were people adapted to earning a ridiculous salary every month, working very little, and experts in stealing or adulterating finances for their own benefit.

In the absence of courses in small business management, investment and marketing, the self-employed have had to learn the laws of capitalism through failures. The most profitable businesses right now are renting rooms, private taxis, photographing quinceañeras, weddings and birthdays. But except for hired drivers, who due to the chaotic urban transport operation generate profits, for every one who succeeds, three fail.

More than 60,000 have returned licenses. Still and all, most consider it preferable to work on their own, giving up the miserable state salary. Then people take risks and make commitments to open their own path. Along the way they have learned to swim upstream.

This is the case with Jesus, a successful photographer who has a good gig taking photos at parties, especially girls’ fifteenth birthdays. “My experience tells me that, aside from the professional quality of your work, you have to know how to sell yourself,” he said in his studio, built in a garage. He pays 10 CUC a month to advertise in the phone book. And he paid 50 CUCs to a sign painter to make a striking lit up sign at the entrance to his house.

Or Gerado, who works renting rooms and advertises on the internet. They are lessons not learned by Octavio, the former owner of the paladar in La Vibora.

In this island version of capitalism in the worst African style, future proprietors have to know that good connections with sellers in the clandestine market are fundamental to not failing. Others try to fall in love with money. It’s customary that, for every customer introduced to a paladar or who rents a room, the owner gives a 5 CUC finder’s fee, and some free food and a couple of beers if it’s a private restaurant.

With such rigid laws that prevent getting rich, one of the ways to move forward with a business is through financial chicanery, hiding income, buying products under the table, using unfair methods of competition, even betraying your competition to the tax police.

That Octavio failed is not a surprise. “In this scene honesty has little value. You have to fight like a dog. Otherwise you won’t succeed. He is a good example.

Although it still hasn’t made it into the history books, Cuba has gone from wild utopian socialism to capitalism. In silence.

Ivan Garcia

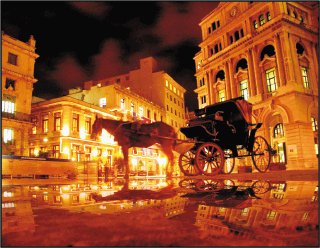

Photo: Taken from Swiss Photographer capturing the contrasts of Cuba, a report published in 2009 in Nación.com of Costa Rica.

23 January 2013