![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 25 October 2023 — All the data is on the internet: how many Cuban soldiers died in Granada, how many surrendered, the weapons of the 82nd US division, the fight between Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher over the invasion, the importance of the airport… but not everything has been told.

14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 25 October 2023 — All the data is on the internet: how many Cuban soldiers died in Granada, how many surrendered, the weapons of the 82nd US division, the fight between Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher over the invasion, the importance of the airport… but not everything has been told.

At noon in the last week of October 1983, while we were watching the Cuban National Television News, shortly after having lunch in the dining room of the ICRT (Cuban Institute of Radio and Television) microbrigade that was building the Yugoslav model building where I still live, we heard the terrible news that the last Cubans fighting on that small island had immolated themselves wrapped in the flag with its single star.

The news was particularly terrible for us, because among those soldier-masons were two of our companions, Fidelito and El Gordo, who had “stepped forward” to participate in the mission to build an airport in Granada.

At that hour the work was halted and we divided into two groups to visit the relatives of our fallen colleagues, above all to tell them, to swear to them, that their apartments, once the building was finished, were guaranteed, that we would see to it that they were handed over to them.

The news was particularly terrible for us, because among those soldier-masons there were two of our companions, Fidelito and El Gordo

A few days later it was learned that the news was not true, that perhaps our companions had not died and that we only had to wait for the contingent to return to count them among the living. And so it was.

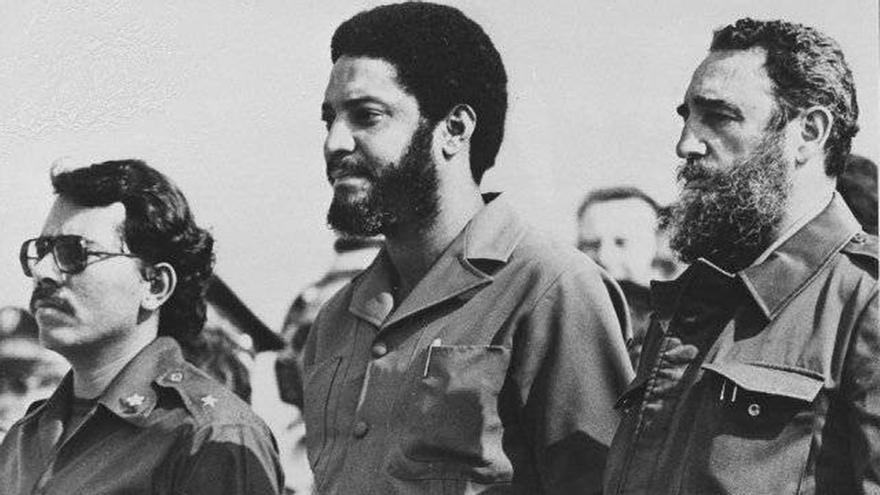

My friend Pirole, a photographer for the magazine Cuba Internacional, installed a camera with a tripod in his house in front of the television that broadcast the reception of those who returned. “That, that’s Fidelito,” I told him, and we managed to immortalize him while Fidel Castro shook his hand on the airport tarmac, just below the steps of the plane that returned him safe and sound. The photo was my gift to the surviving hero.

A week later El Gordo (whom I was unable to immortalize) and Fidelito gave a “private press conference” to their supportive colleagues from the microbrigade.

Fidelito, who had not yet fathered that pair of twins whom he named Fidel and Raúl, told us how he and Colonel Tortoló entered the embassy of the Soviet Union in Granada. I quote from memory: “They didn’t want to let us in because we were armed and a tense situation arose in which neither the bolos [Russians] nor Tortoló gave in, until an agreement was reached to enter through the kitchen door where there was a closet where we had to deposit our weapons, with the commitment to recover them when we were able to leave.”

El Gordo, so witty, told us that, when they raised the combat alarm to occupy the positions they had planned ahead of time, the heroic Cuban combatants had the perception that they would never return to that camp. They were absolutely right, because those facilities were razed. And for that reason, before leaving the site they took to their military artillery site whatever ’little thing’ that each one could save and transport.

They didn’t want to let us in because we were armed and a tense situation arose in which neither the ’bolos’ [Russians] nor Tortoló gave in, until an agreement was reached to enter through the kitchen door

They had received the order not to fire unless they were attacked, and again I quote from memory: “From our cannons we observed how the Marines grouped themselves in combat formations, we heard the noise of their weapons and we saw them advance towards us without firing, until we had them in front of us saying in Puerto Rican Spanish ’Hands up.’”

“Then you told him aquí no se rinde nadie [here no one surrenders]*,” the secretary of the Communist Party in the microbrigade told El Gordo. “No, it didn’t occur to me, what happened was that they stopped us and searched us. I had my hands up and a Marine bigger and fatter than me, checking that I wasn’t carrying another weapon, touched my back pocket. With great care and without ceasing to point his rifle at me, he took out of that pocket the only ’little thing’ I’d been able to save: girl’s underwear for my daughter in Cuba. In Puerto Rican English and without pointing at me he said: ’Excuse me, sir.’ I didn’t know whether to feel grateful or humiliated.”

Forty years have passed. Fidelito lives today in Miami with his twins and El Gordo decided to take advantage of his five-year visa to wait with his entire family for parole on the other side. That Granada airport no longer constitutes a threat to anyone and those apartments that we swore to safeguard now have new owners. None of this appears on the internet, until now, but I, who am still in Havana, keep it in my memory.

*Translator’s note: ‘Aqui, no se rinde nadie’ — Here, no one surrenders — is an iconic phrase of the Cuban Revolution commonly attributed to Juan Almeida Bosque.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.