![]() 14ymedio, Havana, February 8, 2024 — Thirteen years ago, Cuban biologist Ariel Portal, expelled from the state-owned Labiofam and a fervent defender of the healing properties of blue scorpion venom, emigrated to Ecuador and founded his own company, Lifescozul. With a private investment of three million dollars in the last seven years and a team of “renegade” Cuban scientists, the company insists – against scientific consensus – that the toxins of Rhopalurus junceus can cure cancer, and it dedicates its resources to procuring it.

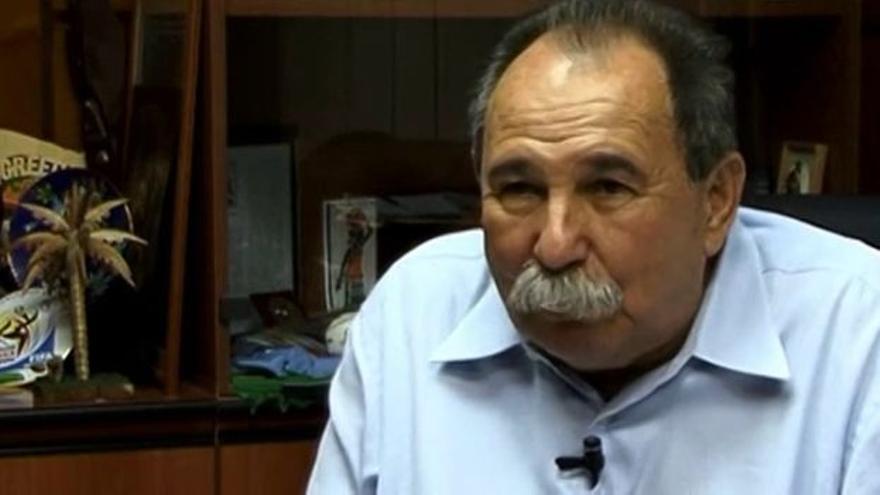

14ymedio, Havana, February 8, 2024 — Thirteen years ago, Cuban biologist Ariel Portal, expelled from the state-owned Labiofam and a fervent defender of the healing properties of blue scorpion venom, emigrated to Ecuador and founded his own company, Lifescozul. With a private investment of three million dollars in the last seven years and a team of “renegade” Cuban scientists, the company insists – against scientific consensus – that the toxins of Rhopalurus junceus can cure cancer, and it dedicates its resources to procuring it.

Concerned that he will be linked to the Cuban regime after reading this newspaper’s recent articles about Lifescozul, Portal answers several questions. The most disturbing: how does a group of researchers, who supposedly broke all ties with their country of origin, get the venom of a scorpion that is endemic to Cuba?

Through “at least” two independent producers who live on the Island, Portal replies. They are the ones who “capture and milk the scorpions,” and then “someone” from the company travels to Cuba to pick up the bottles with the substance. Once abroad, the bottles are sent to the Lifescozul laboratories in Mexico and Chile to check that the substance is not adulterated. “Each venom has its own unique footprint,” Portal clarifies.

According to the biologist, the collection process is carried out without help – or permits – from the Cuban State. In fact, independent scorpion hunters are one of the headaches of Labiofam, the State company, which also manufactures a homeopathic substance based on scorpion venom, Vidatox, whose effectiveness against cancer is denied by Portal.

Lifescozul began as a “service company,” says the scientist, but now considers itself a “pharmaceutical development” company, with allies such as Pharmometrica, a Mexican laboratory that, according to Portal, “analyzes each sample (of venom) and certifies it for our studies.”

The company is now asking its private investors for another 11 million dollars to enter a phase of clinical trials of its product, Escozul. For the company, Portal assures, having private capital “especially in the last five years” has been decisive.

The current structure of Lifescozul – which also works on another kind of products, such as nutritional supplements and vitamins – includes a scientific department, led by microbiologist Alexis Díaz, the “maximum authority” in the venom of the Cuban scorpion; a clinical trials department, headed by Dr. Mariela Guevara; and other marketing, medical care and follow-up teams.

They have a factory in Colombia, a research center in Mexico, and the financing of the project is managed in the United States. The headquarters is located in Ecuador, where Portal founded the “parent company” of Lifescozul in 2009.

Behind each of the people in charge of the company – all former Labiofam scientists – there is a story. Portal himself was dismissed from his position in the state pharmaceutical company in 2006, when he confronted its former director, José Antonio Fraga Castro, Fidel Castro’s nephew. Vidatox, the product manufactured by Labiofam – and one of Escozul’s competitors in the international market – was “a whim of Fraga Castro,” says Portal.

In 2000, scorpion venom as a cure for cancer was one of the obsessions of both the uncle and the nephew, says Portal. “Many patients went to Cuba to look for it because the BBC and CNN reported on its potential.” The pioneer of the studies was Dr. Misael Bordier, a biologist from Guantánamo, who “was never able to publish anything that supported the venom’s properties.”

“Fraga Castro saw the potential, and since he was Fidel’s nephew, he literally took the project away from Bordier, who died in 2005.” Bordier had formed an analysis group including Portal and Alexis Díaz.

The year after Bordier’s death, his colleagues gave Fraga Castro two pieces of news. The good one: that the team had found “evidence” that “inside the poison there are components capable of inhibiting malignant cell growth.” The bad one: that it would take ten years to have a concrete result. At a minimum.

The director of Labiofam was angry, Portal recalls. “The country needs foreign currency now,” was his argument when accepting the proposal of Dr. Fabio Linares, a doctor specializing in homeopathy, who assured that a compound could be sold “as if it were the established final product of the blue scorpion poison.” This is how Vidatox was born.

However, Portal, Díaz and Bordier’s other disciples studied the formula. The conclusion of the analysis, says the biologist, was worrying. “We tested Vidatox on malignant cell lines, resulting in the fact that not only did it have no effect on cancer, but it also accelerates it, and to top it off there was no trace of venom inside the formulation, since it was extremely diluted.” The conclusion, however, has a contradictory aspect: if Vidatox does not contain a trace of the toxin, which of its components “accelerates” the disease?

When they presented the report to Fraga Castro, he was offended. “He accused us of many things. I accused him of being corrupt, and the argument got out of hand. I ended up expelled.” Portal says that, from there, everything was an odyssey for him. He worked cleaning offices at the Cuban Institute of Art and Film Industry until he was given authorization to leave the country. Then he emigrated to Ecuador.

In the case of Alexis Díaz, whom Labiofam refused to free until several years later, he also left Cuba in 2018, to carry out a postdoctorate in Chile. “Díaz was not expelled but was subject to control for a few years,” Portal explains. As for Guevara, who now resides in the Dominican Republic, he is the one who advises Lifescozul in relation to clinical trials.

In 2014, Lifescozul also had a contact in Havana, José Luis Monzón, who raised scorpions, as Portal revealed to Martí Noticias at the time. Monzón died a year after that interview, and now “his daughters continue his work in Jagüey Grande (Matanzas),” says the biologist, who does not offer more details about his work on the Island. However, a 14ymedio reporter discovered that the address provided by Portal to Martí Noticias did not exist. There is also the Bellavista building on 35th Street between 52 and 54, in the municipality of Playa, and no neighbor has heard of Monzón.

“Since 2018, we haven’t had any of our patients traveling to Cuba,” he insists. If anyone requests to go, Lifescozul puts him in contact with Monzón’s daughters in Matanzas. “Misael Bordier’s relatives extract the venom” in Guantánamo, but Portal does not clarify if they have links with the company there.

Portal admits that, as this newspaper pointed out, Lifescozul has indicated to patients that the Cuban Government offers treatments – very expensive – with scorpion venom. However, he says that he has not done so with the intention that they will be treated at the Cira García hospital in the La Pradera hospital for foreigners, founded by Fidel Castro in 1996. “In 13 years of existence we have never sent any patient to those centers. Explaining the costs (more than 1,200 dollars) is enough for them to give up going to Cuba.”

The prestigious cancer research center Memorial Sloan Kettering, founded in 1884 in the United States, has explained that there are no scientific arguments to prove that scorpion venom cures cancer, and the benefits attributed to Escozul or Vidatox “are mostly based on anecdotes, testimonies and experiments that may not have been executed correctly.”

Lifescozul promises to have the papers in order so that, before the end of 2024, they will be allowed to do a clinical trial

Portal does not agree. “We are about to file several patents with an impact on three types of cancer,” he alleges. “We also work on the identification of active ingredients that act on the mechanisms of pain in people with cancer and on inflammation. ” Lifescozul promises to have the papers in order so that, before the end of 2024, they will be allowed to do a clinical trial.

After two decades spent studying Rhopalurus junceus, Portal insists on its “enormous potential” and argues that he knows of more than a thousand cases where the improved product seems to have helped people. However, it is a reality that Escozul, Vidatox and their counterfeits circulate widely on the black market of several countries, and that several “healers” sell them – very expensively – with the promise of healing.

It was the case of Carlos Miguel Castro Ochoa, a “naturopathic doctor” from Mexico, who charged $1,000 for several bottles of Escozul to a patient who ended up dying. Portal emphasizes that his company had nothing to do with it and that, in fact, it collaborates with the authorities to identify illegal merchants who “sell water.”

They are also not involved, he says, with the Cuban health system, which he, Díaz and other scientists from Lifescozul left – not always on good terms. “I don’t work in Cuba and I don’t plan to. Personally, I don’t think they want me there either.”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.