Angel Santiesteban, 13 August 2012 — The painter, Alex Leyva (aka Kcho) has stated in a session of the Parliament of the Assembly of People’s Power, in which he serves as a “deputy,” that artists should work for the people voluntarily and for free without receiving any monetary compensation.”

Angel Santiesteban, 13 August 2012 — The painter, Alex Leyva (aka Kcho) has stated in a session of the Parliament of the Assembly of People’s Power, in which he serves as a “deputy,” that artists should work for the people voluntarily and for free without receiving any monetary compensation.”

At a meeting of intellectuals and artists he attended last February, he also declared that, in general, the state should impose a 100% tax rate on both working and non-working citizens since, according to him, “those of us who are Cuban all emanate from the work of Fidel Castro.”

In his particular case it should be understood that—during the years he was at school, which he quit at an early age—Kcho attended the Gerona School for Special Education, which provided schooling for children with learning difficulties. You might recall the documentary on his work in which subtitles had to be used so that what the artist said could be understood. Thanks to the work of speech therapists, we can now at least understand what he is trying to say.

How is it possible that an artist can ask his compatriots and colleagues to work for a system that exploits them. Of course, it is understandable given the way he explains it. Whenever the Marta Machado Artistic Brigade —named after his late mother, whose greatest achievement was giving birth to him, developing his innate talent and setting him on his way—calls a meeting to “help” the people, it serves as nothing more than as a means of self-promotion and a way to loot municipal and provincial coffers, whose funds he coldly and larcenously extracts.

A few years ago I was invited by the National Union of Cuban Artists and Writers (UNEAC) to visit a camp set up by Mr. Kcho in Candelaria, Pinar del Rio province to provide “artistic” aid to residents who were victims of a hurricane that had left them homeless, impoverished and virtually without food.

After visiting the site and listening to accounts from the camp’s neighbors, I learned that what was actually ravaging the place was the presence of voracious brigade members, who, in spite of the shortages being suffered by the population, were demanding fresh salads, fruits, desserts, wines and other refrigerated luxuries.

The most appalling thing to me was that these expenses were paid not from the artist’s own funds, but rather by the state, specifically on the orders of Fidel Castro. All the televised propaganda that reported on this project served no purpose other than to give a politically false impression.

But the greatest horror experienced there was that the most scandalous orgies were organized under the camp tents. Kcho and the painters who made up his retinue chose girls they found beautiful to serve as companions. They were selected from art schools or taken from their homes with promises to rescue them from the deprivation and hunger they were enduring.

This was done with the consent of their parents, and the support of the school and regional officials, who introduced the girls as a way to satisfy the sexual pathologies of Kcho and his cohorts. Those who went in as young ladies were something quite different when they came out. Many turned to uterine scraping in an effort to undo their pregnancies.

Of course, pigs roasting on a spit were a daily occurrence, at least on the days Kcho chose to be present, since he only occasionally made the sacrifice of sleeping under a tent. He justified his trips to Havana with the excuse that he had to go look for provisions, allowing him to flee the toil and misery left behind by the natural disaster, and to sleep peacefully in the air-conditioned house at “El Laguito,” given to him by his “comandante,” Fidel Castro.

It was worse at Isla de la Juventud (Island of Youth), where he plundered the culture budget to such an extent that there was no money left to pay artists. Year’s end was drawing near and they had not been paid for two months. Might this be what he means when Kcho talks about working for free — a way for him to enjoy luxuries and binges with his friends? With money from the culture ministry he bought televisions and refrigerators, which later, after his stint with the brigade appeared to have ended, were given to family members. The residents observed how his uncles and cousins came looking for these appliances. Is this not theft? And none of it was hidden. So ignorant is he that the did it openly in front of people who, in general, prefer to remain silent to avoid losing their jobs, which are their families’ the only source of income.

His depredation became so great that many of the island’s artists considered going on strike if they were not paid by the end of the year. To get the matter resolved, someone had to call “Ministry of Culture,” which issued a bank transfer to help the artists and calm heated emotions.

That same official, a fan of dominoes, once invited Kcho to play a game, and to this he responded no, because he couldn’t bear to lose. Of what free work, then, would he be talking if he doesn’t know how to lose. Of course, it’s not about him, he gets thousands of dollars for his work, for which we congratulate him, not for asking his compatriots to be slaves which goes against the essence of an artist. It’s absolutely certain that Kcho didn’t read Marti, because he doesn’t know that the Master wrote that Socialism is the highest stage of slavery.

In one of my published books, The Children Nobody Wanted, in fact, the designer chose a photo of an installation that Kcho made with several rafts and inner tubes, precisely because it expressed the pain of Cuban youth who feel forced to emigrate, and in which he was able to consummate the dreams of several generations who through their luck on the sea in hopes of a better future, and of the other great part of the same youth who never get there, so their lives and dreams are truncated, works whose titles speak for themselves: The Road to Nostalgia, The Infinite Column, In Order to Forget, In The Sea Nothing is Written, The Jungle, The Sons of William Tell, Delaying the Inevitable.

Until Kcho was lifted up by power, his work was a reflection of his generation, since then it has become many things, but sincerely and without rancor, we must recognize that his talent has evaporated, and that for several years it’s been a repeat of the same: the pot and the palm.

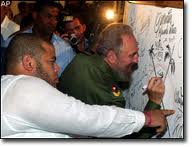

Indeed, back in Gerona, his birthplace, friends, neighbors and acquaintances were always ready for this mania many painters have for drawing on any available piece of paper, and sometimes on napkins Kcho would make some sketch for what would later be a painting.

So he gave his friends these sketches warning them they couldn’t sell them. Some, when they were financially pressed, managed to get a few bills from tourists, and when Kcho learned of it he lashed out against them and ended the friendship. In his little understanding it was as if he didn’t comprehend the neediness of those around him, nor that with their sale they managed to subsist in the daily misery, and that the best measure of a friend is when he can, with his art, provide food and comfort to those with whom he shares a friendship.

Summing up the case, in addition to knowing that the human being Alexis Leyva isn’t one of the great lights, the money he raises for his work, for which we applaud him, and the benefits he extracts from the government, which we criticize, and what he has achieved through his disjointed and unintelligible fanatic adoration of Fidel Castro, has made him the favorite son of the dictatorship, and has led to a level of disconnect with the Cuban reality, such that like a robot he only expresses fatal words, lapses before the history that will recall him and the opportunist he is.

Like many artists he’s only interested in living in the moment, and it is not his fault that he lacks the capacity to assimilate a little bit of the knowledge of history, and not knowing the future, when all the horrors he committed in defending Fidel Castro and his followers are exposed before his eyes, then we will hear that he didn’t know, that he could never have imagined, and, like now, we will have to simply look with pity on his bulk that gets fatter every day at the tables of the Palace, the Council of State. That is his pay: the giant shrimp, huge lobsters, and the arm of the dictator around his shoulders as he poses.

August 13 2012