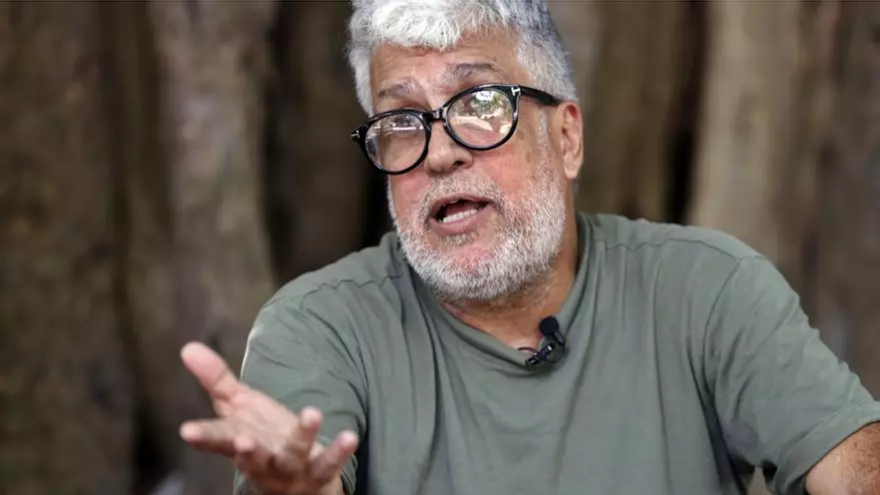

![]() EFE (via 14ymedio), Juan Carlos Espinosa, Havana, August 2, 2023 — The unauthorized broadcast of the documentary La Habana de Fito, by director Juan Pin Vilar (Havana, 1963), in a Cuban state television program this June it has raised a storm inside and outside Cuba and provoked a closing of ranks of filmmakers against the Ministry of Culture.

EFE (via 14ymedio), Juan Carlos Espinosa, Havana, August 2, 2023 — The unauthorized broadcast of the documentary La Habana de Fito, by director Juan Pin Vilar (Havana, 1963), in a Cuban state television program this June it has raised a storm inside and outside Cuba and provoked a closing of ranks of filmmakers against the Ministry of Culture.

The presentation of the most recent film by Pin Vilar – its filmmakers warn that it was not the definitive version – based on a series of interviews with the Argentine rocker Fito Páez, did not come out of nowhere.

In the program that published the documentary – in which the musician touched on sensitive issues such as the death penalty on the island – state television commentators criticized the artist’s words and insisted that he is “misinformed” about the country. Months before, the screening was canceled without prior notice in a Havana theater.

In an interview with EFE, Pin Vilar railed against the decisions made by the cultural authorities – “they have made a mess” – warning that this could even lead the country to lose a lot of money in the courts (the film still does not have permission from Sony) and regretted the censorship to which the sector is subjected.

According to Pin Vilar, Cuba’s Vice Minister of Culture, Fernando Rojas, “called him an hour before” to inform him of the broadcast of the program, despite the fact that the director had not given him permission in a previous phone call with the then director. of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC), Ramón Samada, now dismissed.

“I told him that he had to consult (…) my producer, who is in Buenos Aires, and the distributors (also in the Argentine capital) said no (…) (I) explained to them that this could interrupt the route [of the tape] at festivals (…) However, they, in their heads like little and abusive children, said: “We’re going to put it on anyway,” the filmmaker condemned.

This episode was the seed that led to the creation of an independent assembly of filmmakers, whose first manifesto was signed by hundreds of people – among them Fernando Pérez and Jorge Perugorría – and the tacit support of cultural figures historically linked to the Cuban Government, like Silvio Rodríguez.

The assembly has sought since then to dialogue with the Ministry and has pushed an agenda that aims to end censorship, give filmmakers greater creative freedom and establish a film law.

However, this did not stop a pro-government barrage against Páez – and Pin Vilar – for having been critical of the island’s leaders and, among other things, insisting in the media that the Cuban state cannot blame the US economic embargo for all its ills.

“What astonishes me is not the censorship, [but] what liars they are (…) They begin to create a narrative trying to mix me with the counterrevolution, saying that the ideas that I use in the documentary coincide with a campaign against Cuba,” he says in an ironic tone.

Pin Vilar would not take even one comma away from the critics of the author of iconic songs like El amor después del amor [Love after love] against the Government.

“I am one of the people, like Fito, who thinks that the blockade is a damage that really exists. There is a financial persecution against Cuba… but the fact that there are no tomatoes or that three idiots make that decision (to censor the documentary) It has nothing to do with the blockade,” he concludes.

Nor does he understand those who, from the pro-government circles, justify decisions like the one made with his tape, arguing that Cuba is at war with the US: “It is unacceptable for a young man with half a brain to think that we are at war.”

What happened with La Habana de Fito, as well as the reaction it has provoked from the government – in recent weeks a working group was created to meet the union’s demands – does not give Pin Vilar much hope of change.

“Revolutions are made so that there are freedoms. That is why they triumph (…) Why you do it. It doesn’t matter if it’s the French, the Mexican, the Cuban, anyone. So, to the extent that those revolutions are becoming conservative, they are drifting into dictatorial States, because there is nothing more dictatorial than the conservative,” he argues.

The filmmaker also lamented the brain drain in Cuba, among other things, motivated by actions like the one he suffered with his feature film.

“The most brilliant of my generation are gone, like the most brilliant of this one. Instead of making a critical cinema and a cinema that mentions reality, [they try to make] a contemplative, silly cinema that doesn’t get anywhere,” he says.

The director is not afraid of possible reprisals for saying what he says without mincing words. Though he does admit that he has “concern” and “uncertainty.”

What leaves him calmer and more satisfied is the avalanche of solidarity that has overwhelmed him in recent weeks, especially from young people he doesn’t even know.

“It does excite me because that tells me that the solution to the problems or that the change, as some call it, is possible and probable from Cuba. Not from agendas induced from anywhere in the world, but from Cuba,” he concludes.

__________________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.