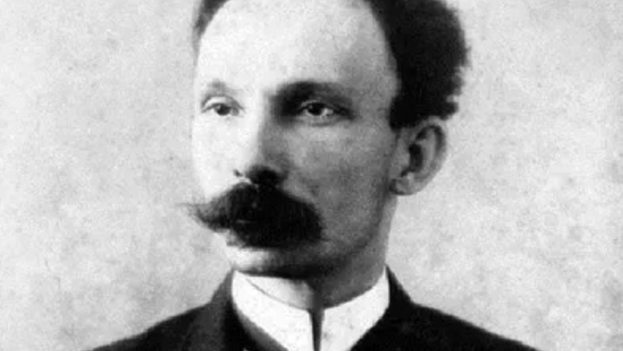

![]() 14ymedio, Ariel Hidalgo, Miami, 30 January 2022 — 19th-century English philosopher Herbert Spencer warned what the consequences of this kind of supposedly socialist project might be. In his book The Future Slavery, he described this conceivable future society as “despotism of an organized and centralized bureaucracy.” And indeed, a notable Cuban analyzed this book in an article of the same name. This Cuban’s name was José Martí.

14ymedio, Ariel Hidalgo, Miami, 30 January 2022 — 19th-century English philosopher Herbert Spencer warned what the consequences of this kind of supposedly socialist project might be. In his book The Future Slavery, he described this conceivable future society as “despotism of an organized and centralized bureaucracy.” And indeed, a notable Cuban analyzed this book in an article of the same name. This Cuban’s name was José Martí.

To understand it properly, it is necessary to read – or reread – the critical analysis of his article. This way we realize that both Spencer and Martí are referring to a specific type of “socialism,” if it can be called that, later known as “real socialism,” based on the State as owner and administrator of the majority of production assets.

In his 1884 article, written several decades before these regimes began to be established, Martí warns about an economic-social system where officials would acquire disproportionate power over workers: “All the power that the caste of civil servants, bound by the need to maintain themselves in a privileged and lucrative occupation, would be gradually lost to the people.” In that system, he says, the worker “would then have to work to the extent, for the duration, and performing tasks that the State wishes to assign to him.”

This path led to a new form of social injustice, a new mode of exploitation of human beings by other humans. “From being a servant to himself, man would become a servant of the State. From being a slave to the capitalists, as it is now called, he would become a slave to bureaucrats.” And he concluded: “Autocratic functionaries will abuse the tired and hard-working masses. Serfdom will be unfortunate and generalized.”

Martí did not stop lashing out at those who, in the name of workers, tried to exalt themselves and lord it over them. Ten years later, in 1894, in a letter to his friend Fermín Valdés Domínguez, he spoke to him about “the dangers of the socialist idea.” What were these dangers? He warned him, above all, about “the arrogance and hidden rage of the ambitious, who in order to rise up in the world, start out pretending, feigning to have shoulders to stand on, as frantic defenders of the helpless.”

The other criticism is based on interpretations that could arise from “foreign and confused” theories. He was probably referring to the later misrepresentations given to the role of the Revolutionary State in the process of socialization of wealth: Should that State limit itself to fulfilling its role as an instrument of empowerment of the workers?

As we already know, the imposed interpretation, both in Russia and in the other countries that followed the same path, was different: to maintain control over that wealth indefinitely as the supposed representative of those workers, and consequently it led to that model that Martí feared and that he called “autocratic functionalism.”

Martí clarified to Valdés Domínguez that his criticism did not mean abandoning the ideal of social justice, because “an aspiration must be judged by what is noble: and not by this or that wart that human passion puts on it.” And then he concluded with his desire to carry out a future struggle of ideas in the Republic to avoid these dangers and finally be able to achieve what he called sublime justice: “explaining will be our job, and smooth and deep, as you will know how to do it… And always with justice, you and me, because the errors of its form do not authorize souls of respectable birth to desert its defense.”

The Active Calm

Martí rejected the path of violence and, in particular, the Marxist theory of class struggle, which is why, although he justified Marx’s indignation at “the bestializing of some men for the benefit of others,” he preached a “soft remedy to the damage.” For him, a process of development of civic consciousness was essential to achieve a just social order, convinced that social justice can be achieved through non-violent means: “Just rights, intelligently requested, will have to overcome without the need for violence.”

In another text he speaks of the “final triumph of active calm.” For this reason, he adds a criticism to his praises of Marx. According to him, Marx “was in a hurry and somewhat in the shadows, not seeing that children who have not had a natural and difficult gestation are not born viable, neither of a country in history nor of a woman at home.

Martí, heavily influenced by American transcendentalists, in particular Emerson and Thoreau, was convinced of the need to develop civic consciousness, and reiterated it in various ways, such as when he stated that what was important was not “the sum of weapons in hand but the sum of stars on the forehead.”

He spoke of an awareness that is not a “class consciousness,” as Marx preached in order to dissent and seize the means of production, but a much deeper radical transformation in human consciousness.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.