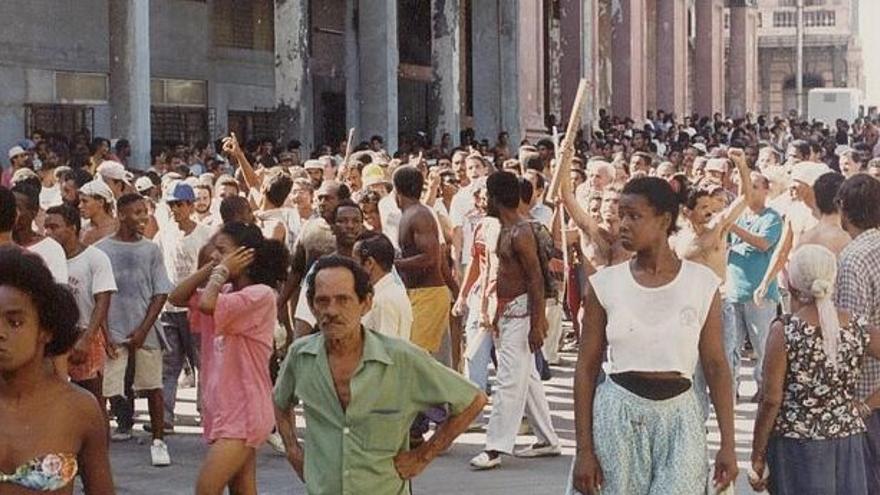

![]() 14ymedio, Yoani Sánchez, Havana, 5 August 2022 — Shirtless and with protruding ribs, this is how the protesters on 5 August 1994 took the Havana coastline during the Maleconazo. The few photos that have been released of that day show faces with sharp cheekbones and a desperate look. From that uprising, continuing to July 11 of last year, Cubans learned several civic lessons and adopted new methods of protest, but the regime, also, has surpassed itself in repression.

14ymedio, Yoani Sánchez, Havana, 5 August 2022 — Shirtless and with protruding ribs, this is how the protesters on 5 August 1994 took the Havana coastline during the Maleconazo. The few photos that have been released of that day show faces with sharp cheekbones and a desperate look. From that uprising, continuing to July 11 of last year, Cubans learned several civic lessons and adopted new methods of protest, but the regime, also, has surpassed itself in repression.

While those who gathered 28 years ago rushed to Havana’s main avenue, desperate to board any ship that would take them off the Island, those of the summer of 2021 were looking not to escape, but to stand up to a system that has condemned them to material misery and the lack of freedoms. The scant cohesion in that earlier outburst, in the middle of the Special Period, has little in common with the compact groups, setting the pace with slogans of freedom and heading towards key points in the cities that were seen on 11 July 2021, the protests now called ’11J’.

In the earlier action, the Malecón wall functioned as a mousetrap between the protesters and the shock troops, dressed in civilian clothes, launched by Castroism against those ragged and hungry people; but a year ago the “organism” of popular protest was already sufficiently evolved to spread through central squares, in front of the institutions of power and travel through streets where new voices were added.

In the Maleconazo, the ruling party tried to avoid at all costs the images of uniformed men repressing, hence the cunning idea of using construction workers and plainclothes police to arrest the protesters, crack their heads with bars, or terrify them with stones. However, the magnitude of 11J was responded to with special troops who were seen deploying countless anti-riot devices that the regime had been buying for years.

The extension of both events also differentiates them to a great degree. In the almost three decades that separate one demonstration and another, the indignation overflowed from an area in the Cuban capital to more than forty points on the island. It was no longer a local event, but a national tremor. Civic genes had mutated enough to know that massiveness and simultaneity were vital. New technologies contributed considerably to the capacity to call out protestors and to document it live and in real time. The Havana residents of the Maleconazo did not even know the depth of their action until years later, with the dissemination of images and testimonies.

But the repressive balance grew. The 11J protests have left at least one dead, more than a thousand violently arrested and hundreds sentenced to prison terms that, in some cases, reach three decades. The DNA of the dictatorship was also transformed. During this time it was organizing in a calculated and cold way to crush its own people if they happened to take to the streets. It invested millions in the equipment of terror, perfected its political police, bought sophisticated gadgets to monitor communications, and further trained its judges and prosecutors to complete the job of muzzling the popular voice.

On 5 August 1994, when the protest had already dissolved and the Malecón was a “safe zone” for the political catwalk, only then did Fidel Castro, dressed in his olive green uniform, arrive to listen to the cheers of the counter-demonstrators who he himself had sent there. Cuban president Miguel Díaz-Canel starred in an even more ridiculous scene when a bottle was thrown at him from a rooftop in San Antonio de los Baños that Sunday a year ago when he tried to mimic the previous march of Castro and his henchmen. Fearing a greater rejection, the engineer ran to hide in the Government Palace, from where he pronounced what will forever be his worst and most famous phrase: “The combat order is given.”

But beyond the differences and notable changes between some protesters and others, there are common lines that unite ’11J’ and its father, the Maleconazo. The exhaustion of the people, the inability of the political-economic model to provide a dignified life, the overcoming of personal fear for the common good, and the desire for democratic change on the Island, these are the identity chromosomes of both moments. The creature that is gestating with both experiences will be more sophisticated and powerful. Let us hope it will also be the final one.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.