![]() 14ymedio, Lilianne Ruiz, Havana, 6 November 2015 – He arrived in Berlin without a single euro in his pocket and with a pound of beans in his suitcase. Ariel Urquiola remembers his arrival in Germany to do post-doctoral work at Humboldt University’s Leibniz Institute. His departure from Cuba, like that of so many young specialists, was motivated by the desire to do serious science.

14ymedio, Lilianne Ruiz, Havana, 6 November 2015 – He arrived in Berlin without a single euro in his pocket and with a pound of beans in his suitcase. Ariel Urquiola remembers his arrival in Germany to do post-doctoral work at Humboldt University’s Leibniz Institute. His departure from Cuba, like that of so many young specialists, was motivated by the desire to do serious science.

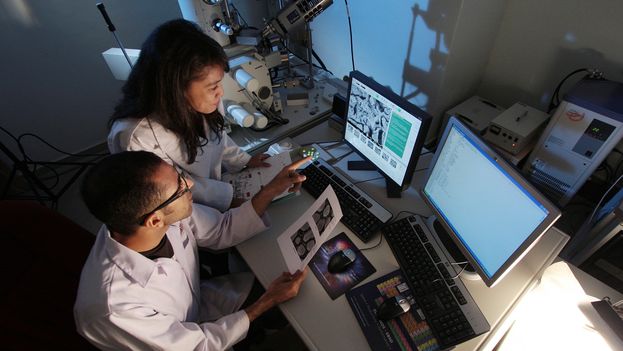

After graduating and earning a doctorate in cellular and molecular biology, Urquiola felt he had reached his peak inside the island. He was looking for a laboratory where he could examine zoological specimens but the lack of available technology didn’t allow him to study in his own country.

“Here I could work with at most one species, and in year have limited results,” he related during a visit to Cuba. “In contrast, in Germany, in just a month and a half I was able to process 503 samples,” that had arrived in Berlin from Cuba through institutional channels, he related with satisfaction.

His work consists of analyzing samples of the zoology of the Sierra de los Organos mogotes in Cuba’s Pinar del Rio province, research that he continued at the Leibniz Institute. The eyes of the young scientist shone when he explained that the results of his study might conclude that the population of the area by wild species “is much more ancient that is thought.” Like many other Cuban university graduates who have emigrated, he feels that abroad his work has potential.

In comparison to doctorates earned within the country, options abroad have a much more professional profile, according to the majority of those surveyed. A young Cuban biochemist who earned her PhD at the Catholic University of Chile points out “the quality and importance of scientific journals where research results are published.”

Cuban university students can choose from among more than 300 scholarships offered to PhDs by foreign governments. Many decide not to return to the island after having benefitted from one of them

Dr. Ileana Sorolla, director of the Center for International Migration Studies at the University of Havana, said in the journal Alma Mater: “Cuban employment centers need to readjust (…) to try to recover talent, so that returning to the country is an alternative. And not just because of an ethical, moral, political and ideological commitment, but also for business advantages.”

According to the official, looking at migration patterns of Cubans today, “some 23.9% are people with a university education,” and “around 86% of professionals who emigrate do it before they are 40.”

The subsidy that accompanies these scholarships abroad is also a motivation to apply for them. In the case of the German Academic Exchange Service, the researcher receives a monthly allowance of 1,000 euros to cover living costs, plus assistance for travel expenses, health insurance and a lump sum for study and research, among other secondary benefits.

Although the cost of living is much higher in these countries, conditions are incomparably better for these high-achieving university graduates, used to living in Cuba under the same roof as their parents and grandparents, unable to even afford dinner at a restaurant.

Just outside the Canadian embassy in Havana, several young people were waiting on Monday to start the consular procedures. A couple was reviewing all the documents they would present at an interview for the expeditious entry program to qualified professionals who want to settle in that northern country. Each year, 25,000 places are awarded worldwide.

Candidates must pass tests of English or French, deposit an amount of $ 5,000 in Canadian funds in a bank account in Canada, and confirm that their profession is included in the National Classification of Occupations. The applicant’s and spouse’s ages and levels of education are also considered for granting residence visas. This path is widely used by graduates of scientific specialties in Cuban universities.

The one in greatest demand is the program to settle in Quebec, which does not require a bank account in Canada, but applicants must give proof of sufficient funds to cover travel and subsistence. On the consulate website all the details are explained, but given the poor internet connectivity on the island, the information spreads by word of mouth.

Planning to settle in Quebec is Maikel Ruiz, holder of a degree in mathematics from the University of Havana, who considers that the financial benefits are not as important as the passion for scientific discovery. “When a professional is accustomed to living with an income below 40 convertible pesos a month, getting above the poverty threshold allows you to dedicate yourself completely to what interests you most.” It is not about “the mere fact of making money, eating or dressing better” he says.

Ruiz is the only graduate of his year who remains in Cuba, and currently teaches private math classes to high school students to pay for the legalization of his university degree*, an airplane ticket and the emigration paperwork that will bring him to “the land of snow and opportunities,” as he calls it. The visa alone costs 445 convertible pesos (CUC).

If someone wants to do probability mathematics at the theoretical level, they will consider going as a scholarship recipient to Paris or Toulouse,” explains Ruiz. “If they are interested in Geometry, they will think about the United States or Germany,” he points out, although he also believes that “to get this training in a dynamic system it’s better to go to Brazil or France, and those interested in number theory, they will do well in Hungary.” As he speaks it’s like watching him stick colored pins into an imaginary map, but none of them are stuck in Cuba.

For Cuban mathematicians, as for other scientists, the world out there seems an infinite universe of opportunities. “Mathematics needs to be engaged in with new technologies,” reflects Ruiz, sure that as a specialist in his field he will have many work opportunities.

Dr. Urquiola is one of those few professionals who undertook the path of emigration and who now returns frequently. He carried out several projects in Pinar del Rio, including the development of an agroforestry farm in Viñales where he created a nursery to preserve Cuban timber species. “I am working hard with local authorities so that they will allow me to find ways of doing this work,” he says, with that air of tenacity that is achieved when one is “coming and going.”

*Translator’s note: Emigrating Cubans must pay fees that can run into the hundreds of dollars to the Cuban government to get certified copies of their degrees or professional experience.