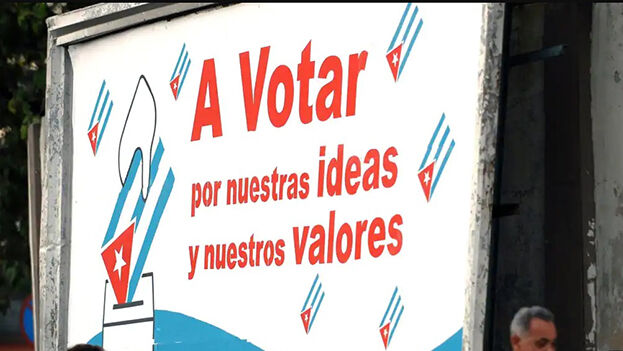

![]() 14ymedio, Ariel Hidalgo, Miami, 30 October 2022–The proposals by the internal opposition in Cuba, announced by the Council for a Democratic Transition as well as the newly created D Frente, to promote candidates to the municipal elections are not naïve as some critics have said. Rather, it could be said that those who believe so are more naïve. The proponents know perfectly well the barriers and risks they will face. Even if they were convinced of the impossibility that any of the candidates could reach any of the levels of that official institution, it is worth fighting for other reasons.

14ymedio, Ariel Hidalgo, Miami, 30 October 2022–The proposals by the internal opposition in Cuba, announced by the Council for a Democratic Transition as well as the newly created D Frente, to promote candidates to the municipal elections are not naïve as some critics have said. Rather, it could be said that those who believe so are more naïve. The proponents know perfectly well the barriers and risks they will face. Even if they were convinced of the impossibility that any of the candidates could reach any of the levels of that official institution, it is worth fighting for other reasons.

To understand this, it’s sufficient to review the experiences offered by the history of the dissident movement itself, such as that of the first Cuban who accepted this electoral challenge.

The first time an opposing candidate ran in an election in Cuba was 1989. Roberto Bahamonde Massot, an engineer and doctor of pedagogy, member of the Party for Human Rights in Cuba, which was one of the first dissident organizations, nominated himself as a candidate. However, his own group refused to support him, as they believed that it legitimized fraudulent elections.

Bahamonde was undaunted and decided to run in his personal capacity; he made several copies of his candidate program and distributed them in the neighborhood. On March 9th of that year, he arrived at the meeting for the candidates for delegate of District 2 in the area of La Fernanda, in San Miguel del Padrón. When it came time for nominations, he nominated himself, which caused a great stir in the asembly because he was someone who had been arrested four times by State Security and they refused his candidacy. But he did not give up and challenged the legality of the procedures. The commission agreed to repeat the meeting. He competed against the Minister of the Interior and lost with 31 votes in favor, 60 against and 59 abstentions, which was a great victory in the country of unanimity.

The fact that back then Bahamonde “lost” while obtaining over half as many votes as the officialist candidate, and that 59 people abstained despite the closed campaigning orchestrated by State Security against him, is very significant. It was clear that those who abstained did not want to vote for the officialist candidate, but did not have the courage to vote for the dissident. Were it not for that fear, Bahamonde would have flat out won with no fewer than 80 votes.

The question to ask now is: If that occurred in 1989, what would occur nowadays when almost no one is hopeful that this leadership and this model will improve the desperate conditions for the population that has launched into protests in the streets in almost every city in the country?

It does not mean they will win some seats now, because, for the same reasons, repression and fraud will be on levels greater than before. What matters is the political costs they will have to pay when they realize this, not only when facing the people, but also in international public opinion.

For those who think that these costs don’t matter to them, I want to remind you that faced with an economic situation so severe, they are in no condition to continue losing foreign aid, or deserters from among the skeletal base of popular support. Success depends, of course, on the one hand, on the opponents succeeding at reaching the population with their candidacy programs and those of the opposition in general. On the other hand, foreign lobbying is important so that any benefits the government negotiates with powerful institutions are conditioned upon allowing the presence of international impartial election observers.

The greatest support that exiles who fight for their country’s freedom can provide is not so much to exhort their compatriots on the archipelago to abstain from arguing that the elections would be fraudulent, nor to pressure governments to strictly deny any concessions to the Cuban government, but rather to exhort them to vote for opposition candidates and, better yet, aim for foreign governments to condition foreign aid on the acceptance of those observers. If the oppressors refuse, they not only lose that aid, but also what little credibility they still have.

The true battles will not really be at the polls, but rather, in the streets, in the population’s peaceful protests in defense of the rights of the people’s true candidates, all of which would further nourish the ranks of unsatisfied citizens. On the other hand, in the international arena, we’d gain allies while the oppressors get cornered further.

For my part, I’d view such a victory not only as a precursor to the final triumph of the libertarian ideals of so many Cuban fighters, but also the best way to honor the memory of that forerunner who, I know, died after being forgotten in exile.

Translated by: Silvia Suárez

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.