Since Thanksgiving was celebrated last Thursday, marking the beginning of the Christmas season, I offer these reminiscences.

Since Thanksgiving was celebrated last Thursday, marking the beginning of the Christmas season, I offer these reminiscences.

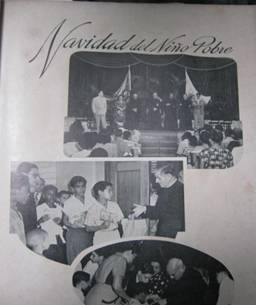

Every year during the month of November funds were collected by every student through the sale of raffle tickets. The proceeds were used to assure Christmas for a Poor Child, which is what the campaign was called. Its only objective was to hand out boxes of food before Christmas Eve and toys on Day of the Three Kings to poor children and their families who lived near the school, which was located in the neighborhood of La Víbora. The meaning of poor referred more specifically to those in need, since there was no discrimination against anyone nor any prior investigation to determine who was or was not poor. Whoever considered himself to be so, or who so desired, simply had to show up to collect a box and a toy. In those years the prevailing ethical concept was that no family which did not consider itself to be needy would show up to collect anything, nor would it allow its children to do so, since this would have been understood to be both immoral and degrading. This guaranteed that acts of charity were organized, calm and fair, leaving everyone pleased and grateful for the gifts they received.

For students like ourselves the sale of raffle tickets was an arduous task, since we had to sell them to our family members, friends and neighbors — the ones most affected. After the aunts, uncles and godparents, there were the shopkeepers, the butcher and all the other tradesmen with whom our parents did business. They almost always obliged. There was competition among the different grades to see who could raise the most money. The figures were displayed in thermometer graphs, which were drawn on one side of the blackboard and where the progress of the collection efforts was updated weekly. There was a classroom set aside to hold the various grades’ thermometers and the amount they had collected was recorded on the blackboard in colored chalk.

In the euphoria of the competition we sold more and more raffle tickets, requesting new booklets once we had liquidated the old ones in the hopes of making the thermometers explode at the top, which was considered a triumph. The price of each ticket was twenty centavos and normally the total take was between three and five thousand pesos. This money was put to good use buying food and toys at favorable prices, which allowed many people’s needs to be satisfied. This practice was routine in most religious schools and brought additional happiness to the Christmas holidays in those places where the custom was established.

In the euphoria of the competition we sold more and more raffle tickets, requesting new booklets once we had liquidated the old ones in the hopes of making the thermometers explode at the top, which was considered a triumph. The price of each ticket was twenty centavos and normally the total take was between three and five thousand pesos. This money was put to good use buying food and toys at favorable prices, which allowed many people’s needs to be satisfied. This practice was routine in most religious schools and brought additional happiness to the Christmas holidays in those places where the custom was established.

Everyone took on this task, not as a burden, but as a just and necessary cause. It took place in an atmosphere of happiness, which gradually grew as we, along with the city and the country, were taken over by the Christmas spirit. I do not remember that anyone who received presents — the truly needy — felt either offended or looked down upon as a person for having to accept them. I did know of cases where people accepted them one year, but the following year did not — an indication that they no longer needed help because their economic situations had improved. Cubans were honest and felt a sense of solidarity with others.

In La Víbora, which was not a poor neighborhood, families living there were proud of the Christmas activities which the religious schools sponsored. In those very different times these activities were another reason for happiness, along with the well-known but now forgotten custom of the Christmas bonus — as much as a month’s salary — which was given to employees at their places of work, making the celebrations of the season more feasible.

In spite of its name Christmas for a Poor Child was really a humanitarian effort to make the holiday happier, more joyous and more comprehensive every year. We all felt good, those of us who gave as much as those who received.

Archive photos.

Author’s note: In my previous post, dated 11/22/12, I cited ITT when I should have written Electric Bonds & Share. I apologize for the error. [Translator’s note: The error has been corrected in both Spanish and English versions of the post.]

November 25 2012