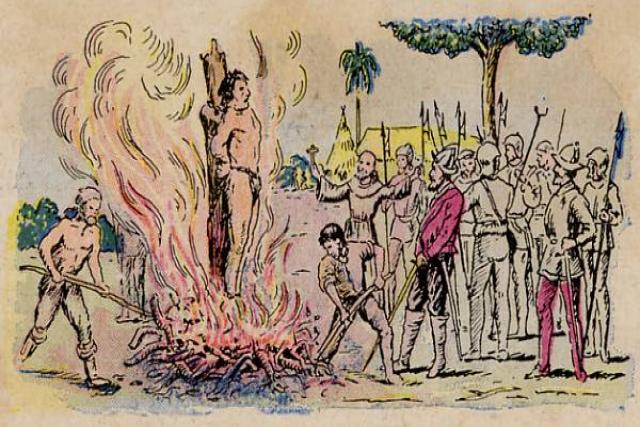

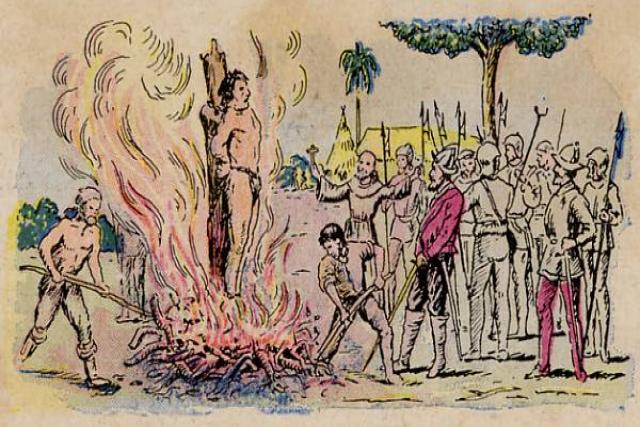

The torture of the opponent Hatuey

HAVANA, Cuba, April, http://www.cubanet.org- On Monday, April 8th, Cubanet published an article by colleague Jorge Olivera Castillo (Equilibrar la Balanza), which was as surprising as it was regrettable. A fellow traveler who has proven his courage and integrity in the fight against the dictatorship and shared spaces with numerous members of the independent Cuban blogosphere should be more serious and careful when expressing himself.

Perhaps Olivera may have had a bad experience and some day he will understand that lies and veiled criteria do not replace opinions and arguments, but neither do I think it fit to keep silent in the presence of what I consider at least unfair and inaccurate, so to speak. I’m a blogger and freelance journalist, so I feel alluded to in his article and make public my displeasure.

Optimism should not be confused with “triumphalism”, as my colleague Olivera refers to the expectation triggered by the blogging activity of over five years, and also unfortunate is his question about “what the impact could be (of blogging) within national boundaries, when the vast majority of Cubans do not have a computer or internet connection possibilities”.

That observation is doubly unfortunate because, first, although most Cubans don’t have free internet access and that hinders full dissemination of our work, I do not see that any other dissident faction has better possibilities to present their proposals quickly and effectively, and second, because a significant number of bloggers have been the voice of many Cubans, which has proven useful when reporting violations and mobilizing solidarity for all repressed, including political prisoners, and especially the prisoners of the Black Spring.

Olivera asks “how many Cubans would be able to become tweeters, when each transmission costs a little just over a dollar in a country where the average salary is around $20 a month”, and I would ask him how many he thinks would be willing to march through the streets following opposition leaders, demanding their rights or protesting the against the excesses of government. I would also ask him why all those opponents, whose mobile phones are regularly recharged by friends and supporters from outside Cuba, are not tweeters, and what prevents a freelance journalist from opening his own blog and a Twitter account, thus strengthening his voice and those of others to the extent they are willing to do it.

It is possible that the ignorance of the complexities of the blogger phenomenon continues to produce some fears as to the feeling that this is a privileged caste. Many are unaware that maintaining a blog from Cuba has been a source of expense, rather than income, for us. We don’t charge for posting our ideas in a blog, but we have to spend our own money on cards to connect from public spaces in the city so we can keep our personal sites updated.

Our efforts aroused the sympathy and support of many friends who began to give us cards, helped open up many doors, and there even appeared some who were trained to upload our posts when we could not do it. Interestingly, before the renowned blogger Yoani Sanchez won her first Ortega y Gasset award, nobody seemed perturbed that there were at least five active independent blogs in Cuba, or worried about how we managed to post regularly on our web platform. In fact, hardly anyone knew what a blog was around here, and still there are those who are completely unaware of the use of this tool and perhaps that’s the reason they prefer to discredit it rather than to learn how to utilize it.

Another error is believing that the independent blogosphere is “the culmination of a process that spans more than three decades of sustained efforts on the part of hundreds of human rights activists, political opponents, independent journalists and librarians …”, not only because all social or political processes are heir to the accumulation of multiple previous experiences and circumstantial factors, but also because the blogger phenomenon does not represent a culmination in itself, but a conveyer of its own dynamism, barely a phase that will inevitably continue to transform itself into the evolution of civic struggle against the regime.

In fact, for a long time, several bloggers were previously in the process of developing intense dissident activity, either as independent journalists (as in the case of Yoani Sánchez, Reinaldo Escobar, Dimas Castellanos and this writer, among others), or as editors of the first digital magazine, edited and directed from Cuba, which -by the way- did not pay for the contributions of collaborators, since it absolutely lacked any funds or funding, which is why many independent journalists who today attack bloggers refused to collaborate in it then.

Therefore, it is not about that “bloggers reached dissidence”, but exactly the opposite: many dissidents -some hitherto unknown- became bloggers.

Of course, everything has a history, but not necessarily that which colleague Olivera indicates, but the key point is to understand who is considered sufficiently qualified or licensed to narrow historical margins and the inferences and influences of each phenomenon. In that vein, we should recognize the Indian Hatuey and Guamá as the parents of the current Cuban dissidence, for they were “first” in insubordination … We need a bit of contention, don’t you think?

Among the bloggers who now are now the focus of so much discredit -and not only from the authorities, apparently- there are some who had even belonged to opposition parties from before. It is not only about our “new generations” of dissidents. I take this opportunity to make a timely comment: there is no dissident pedigree that allots special merits to those who have been imprisoned or have “arrived before,” as the term is applied by the government, depending on whether or not someone came over on the yacht Granma, was in the Sierra Maestra or not, etc.

To my knowledge, no opponent has been imprisoned by choice but by the arbitrary and repressive sign of a government that we all fight against, that attributes itself the prerogative to select how, when and to whom to apply it, without anyone -before, now, or after- being able to consider himself a sort of supreme magister or chosen one because of it. I, for one, do not aspire to a “merit” that doesn’t even depend on my political performance, but on the sinister tricks of the Castros. The goal is to reach democracy, not the dungeons.

The alarmism that Olivera oozes in the mentioned article seems to derive more from a mixture of animosity and frustration than from some genuine concern, when referring to a supposed “over-dimensioning” for the use of the Internet as an anti-dictatorial tool, or when -at the opposite end, under-valuing such activism- he slips in the phrase “the main question takes route in intramural influence, and that probability is far from realization through the use of the web”.

With all due respect, it turns out to be more hilarious than offensive, but we need to be realistic: the existence of blogs does not block anyone’s dissident path, and we bloggers have never considered that the simple use of the Internet constitutes a kind of secret weapon capable of influencing, by itself, the collective consciousness within Cuba.

However, I would dare say that, since it is capable of creating solidarity networks, up-to-date underground information, and establishing bridges among the different forms and “political and civil entities”, such as Olivera terms them, the blogosphere has demonstrated ample capacity and efficacy. No wonder there have even been special programs dedicated to blogging activity and tweets broadcast on Cuban radio stations abroad reaching a large listening population on the Island. Perhaps the journalist should have researched beforehand with the dozens of tweeters in Cuba whose best weapon for protesting and personal defense has been precisely a cellular phone with a Twitter account.

I firmly believe that if Olivera had heard “rumors that could be the seed of unfortunate ruptures in near future”, he should have stopped them. Rumors only thrive on the receptive ears of those who are willing to pass them on. That may be why no one comes to “rumor” anything with me. I would not allow anyone to speak ill of the efforts of my fellow travelers, whether journalists, figures of the opposition parties, librarians, bloggers or tweeters. Anyway, the “reasons” for a scam are never as “obvious”, as the colleague claims. The tangles are simply not rational, but emotional, and in all cases, counterproductive.

We could expand into a debate that, far from harmful, would be useful for banishing such an attitude, but it might be better to summon the “preoccupied” to a face-to-face discussion, without “rumors”. Suffice it to remind the colleague and those who have not heard it yet, that, to date, since its inception, the blogosphere has not only consolidated, but in its midst are people who are generous enough to share their knowledge and to multiply it in a community that increases the voice of numerous sectors of Cubans of all beliefs and leanings, thus shaping many who are now able to spread a whole spectrum of opinion and information that otherwise could not be accomplished in such a short time.

Personally, I would never dream of putting the work of any dissident group, or of that of any rebellious brother, on a “scale”. The efforts of all Cubans, on any shore and position, to achieve Cuba’s democracy seems invaluable to me. It would be truly more productive for us not to worry so much about the visibility or the awards any of our colleagues receive. Let’s celebrate their well-earned victories together, and above all, let’s take care to balance the underlying emotions.

Translated by Norma Whiting

19 April 2013