I originally published the article that follows on the website Penúltimos Días last November 26th. Since there are several and conflicting opinions about the post, I will submit it to the regular readers of this blog for their consideration. I just want to make a preliminary clarification: what some may consider inadequate demands of the Spanish government, which, according to them I should also make of the Cuban government, I will remind that my words are based on words of the Consul of that country in relation to Cubans who have obtained Spanish citizenship, which includes me, and which gives me the right to review the decisions and actions of that government’s policies. On the other hand, readers have witnessed my habit of demanding the rights that are due me as a Cuban.

Here goes:

Ravings of a Cuban-Spaniard

A few days ago, I read a note published by the editors of Cubaencuentro, dated in Madrid on October 30th under the title “Spanish Consul in Havana asks Island Hispanic societies to welcome new Cuban-Spaniards”, which seemed a bit perplexing to me. Besides offering some interesting facts, the article deserves careful reading: often, the essence is in the details, especially when it is a diplomatic discourse, full of omissions and half-truths.

The issue of the Cubans who have crowded the headquarters of the Spanish Consulate in Havana in order to qualify for the nationality of their ancestors under the Law of Historical Memory is an eloquent sign of how depreciated the condition of native-born Cubans is. Suffice it to check the figures to get an approximate idea of the mobilization unleashed by hundreds of thousands of Spanish descendants who in the last three years have sought to restore the citizenship of their grandparents.

According to that note, admissions by the Consul General of Spain himself, Tomás Rodríguez Pantoja, at the end of 2011, 65,000 new Spanish citizenships have been granted, and 70,000 have been obtained to date, while 140,000 requests still remain. If we add to that the 28,000 Spanish nationals who were living in Cuba before the application of that law, you can easily conclude that the number of citizens of this country (i.e. neo-Spanish Caribbeans) that have emerged in a few years almost exceeds the total Spanish immigrants who arrived in Cuba in the first third of the last century. These figures do not include the tens of thousands of Cubans of Spanish descent who, for various reasons, have been unable to obtain the necessary documentation required for requesting Spanish citizenship -as, for example, the grandparents’ birth certificates- and, consequently, have not even submitted their applications to the Consulate.

In a meeting held with the leaders of Spanish associations in Cuba, the Spanish Consul stated that “one of the biggest challenges we have, and I ask you to take this with the deepest affection, is to integrate into our societies the vast number of new or old renovated Spaniards, Spanish-Cubans who, through the Law of Historical Memory, will recover their ancestors’ nationality” and he asked that the Spanish communities assume “the responsibility of integrating them into the spirit of Spain” since some of the nationalized [Spanish] Cubans “can’t even tell the difference between communities”. He had previously stated, in another instance, that these people “don’t yet have the Spanish sense (…), don’t feel for our country or are united onto our reality, though they are as Spanish as we are”.

As a recent Spanish-Cuban, I must admit that, to a certain extent, the Consul is right: around here, we don’t even have the vaguest idea of how “having a Spanish sense” might feel, at least not in the same way as the diplomat might regard it. We are, simply, and purely, Cubans, regardless of the number and variety of citizenships or passports that we might come to cherish if we could. It is no secret, even to the consul, that the overwhelming majority of those who have benefited from Spanish citizenship has done so in the hope of emigrating, and, by the way, a Spanish passport is not in as much high demand as an American visa.

And at this point I want to emphasize that I am the exception to the rule: I have no interest in escaping from Cuba, or settling in Spain (or any other country) and if I decided to take my grandfather’s citizenship, a Basque born in Busturia, is because I have the right, and if one day I have the possibility of visiting Spain, it would be better to do so as a citizen of that country, with a passport that would open the doors that my Cuban passport closes for me. I’m definitely an incurable addict when it comes to rights. I’m not interested in “asking for help” to be a parasite on the public purse sustained on the taxes of the Spanish, to which they contribute with their work and effort. I have neither a lazy nor a beggar’s soul.

Personally, I have no idea what the consul means by “a Spanish sense” I don’t think that a nationalist feeling is necessary to experience deep emotion in the presence of the Spanish history and culture. The great masters of the art of Spain, her artists and the numerous geniuses of her literature, especially her poetry, with Antonio Machado as my favorite, the force and uniqueness of her music and dance, the richness and variety of her traditions, the fascination of her rich history, full of light and shadow, which largely holds the key to the very course of the history of my country, Cuba, and also explains the idiosyncrasies of my own nation and identity, are sufficient elements to understand the singular empathy between Cubans and Spaniards.

Spain is closer to me, in addition, since a reverse migration began to take place: decades of dictatorship have contributed to the displacement of thousands of Cubans who have made Spain their adopted country. Many of them do not have Spanish citizenship, and a considerable portion hasn’t even obtained legal residence, but they do their best to survive from a disadvantaged position in the midst of a prolonged and severe economic crisis. I love Spain more since it has become home to so many of my countrymen, and since, for the past five years, I have received the support and affection of Spaniards who write to me and follow my digital blog, because, though this may not be important to Mr. Consul, I understand that the Spanish government might not have made a good investment when it gave me my citizenship: I am an unrepentant dissident, and I oppose any authority abridging my rights. As a Cuban, I oppose the Cuban government, and as a Spaniard, condescending speeches aside, I would love for the Consul, representative in Cuba of my other nation’s government, to clarify some of my doubts.

I would be interested to know, let’s say, how the Consulate is going to help those Cubans who are recovering the nationality of their ancestors “have a sense for the country (Spain)” or “join” the Spanish state of affairs. Let’s say, for instance, that the Spanish diplomatic seat in Havana could start by introducing practices that recognize the rights of Cuban-Spanish as the same ones of Spanish-born citizens, since, so far, treatment given to the former and the latter is markedly different, as evidenced by the detail that native-born Spanish need only present their passports or their Spanish identity cards to gain access to the embassy, while Cuban-Spanish are required to use their Cuban identity card to do so, though they have Spanish passports. Are we second-class citizens without pedigree, amateur Spanish?

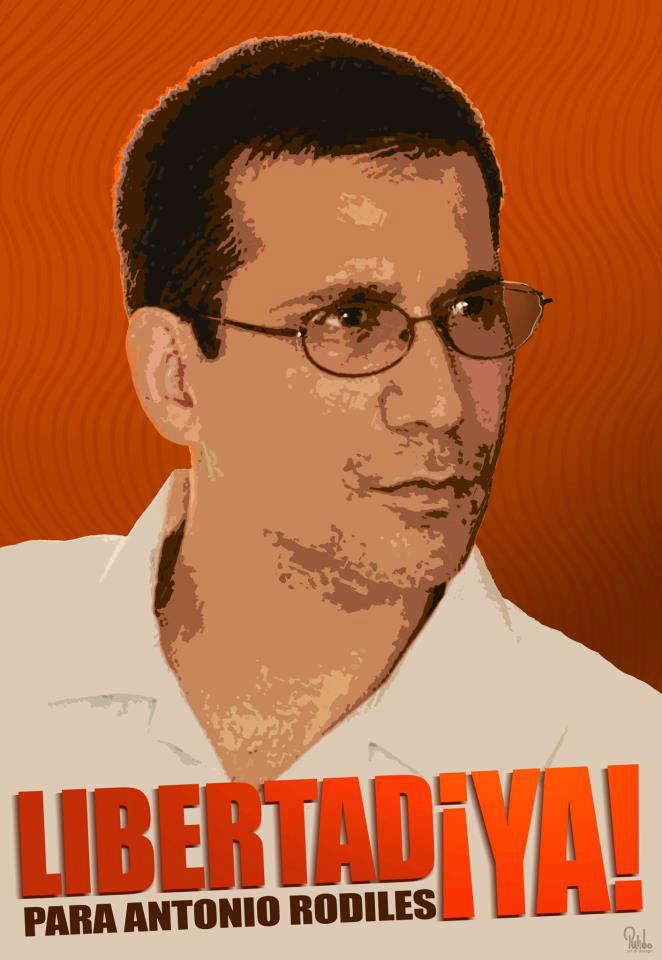

The passport is another fundamental point. It is almost as cumbersome to obtain a Spanish passport as to get a Cuban one. In my case, I was given notice of having been granted my citizenship in October, 2011, and over one year later, I have yet to procure a passport, and I don’t know why. A lot of Cubans who got their citizenship after I did already have theirs. For lack of answers, I have applied several times, without success. I am registered in the Havana consulate, but I am an “undocumented Spaniard”, without knowing what bureaucratic ineptitude (if only that were the case!) prevents me from accessing the document that identifies me as a citizen of Spain. Could it be that the Spanish passport is as selective as its Cuban counterpart and certain people have no right to it?

I know of no new Spanish-Cuban who has been invited to the Columbus Day celebrations held each October 12th, and haven’t heard any news that the consulate has given any attention to this sector of its “nationals”. For example, despite the known limitations of Cubans to access the Internet, all consular procedures require prior appointments to be requested by e-mail, however, the consulate has not seen fit to enable a location with access to the web, even for the use of Cubans who have already obtained their documentation as Spanish citizens. The service is likewise not offered in cultural Spanish associations. Wouldn’t this be an effective way for the Madrid government to demonstrate its good will and a way for the new Spanish citizens to be better informed about their adopted nation? Aren’t the new computer and informational technologies the most expeditious means to the free cultural exchange in the so-called global village?

Nor do I know of Spanish-Cubans who are freely contracted and considered as such by Spanish companies that have invested capital in Cuba. What prevents them to be hired as overseas Spaniards and enjoy the same benefits and labor rights? Similar exclusions extend to those who have decided to become independent from the official employer –the Cuban government- after obtaining their Spanish citizenship. I know of Cuban cases that, while they were contracted through an official Cuban employment purse, they could practice their profession in Spain without the need to be re-qualified in that country, however, when they tried to get employed as Spanish citizens doing the same work, now they demand Spanish education credentials. Could it be that there is an agreement with the Cuban government to limit the rights of Spanish abroad? How can the “Spanish feeling” be consolidated this way? How would the consul explain such discrimination and how does he suppose these neo-Spaniards will be able to “penetrate” the economy of their companies when in principle they are marginalized?

I don’t think Mr. Consul is very clear in that integration cannot be sustained only on “trade and cultural activities.” That is, tambourines, castanets and bagpipes seem all well and good, but as “rights”, they are insufficient. Spain’s government could do much more for the Spaniards on this Island and also for its own nation if it conceived effective policies that stimulated them [Cuban-Spanish] to remain in Cuba while benefitting the Spanish economy. In fact, that is just what men like my Basque grandfather and hundreds of thousands of Spaniards did. Like him, they arrived on this Island hopeful to work, prosper, and help their relatives in the distant homeland. We are not talking about offering handouts, but drawing mutually beneficial strategies. If only Spanish policy makers in Cuba today were so determined, creative and authentic as those immigrants, who long ago left their beaches to make landfall on ours!

Translated by Norma Whiting

November 30 2012