Dimas Castellano, 7 July 2021 — The democratization of Cuba, a Western country laboring under a totalitarian government in the twenty-first century, is an urgent necessity. Cubans, who lack the space and freedom to participate as agents of that change, require international support. After 25 years of mutual relations, the European Union (EU) has shown the requisite conditions to satisfy that role as a partner.

The European Economic Community (EEC) was created in 1957 by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, and West Germany. With the signing of the Maastricht Treaty after more than three decades in development, it added political ties to its economic relations and went on to be named the European Community (EC). At the summit meeting of the heads of state or governments of the member countries, it then became the EU.

In 1996, the EU, whose members maintained bilateral relations with Cuba, assumed a Common Position with the objective of “fostering a transition to democracy and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, as well as a sustainable recovery and an improvement of living standards for the Cuban people.”

A retrospective view of 25 years of relations with Cuba bears this out.

In 2002, Cuba sought to be incorporated into the Cotonou Agreement, a cooperation agreement between the EU and countries of Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific, in which the parties are obligated to respect human rights and fundamental liberties.

In 2003, as the application was about to be approved, the imprisonment of 75 peaceful combatants and the execution by firing squad of three young people who attempted to flee Cuba, disrupted the negotiations. In response, the EU limited its governmental visits to Cuba, reduced its participation in cultural events and invited the opposition to participate in receptions for the national festivals of its member states. continue reading

In 2008, while the majority of the 75 prisoners remained in jail, and the effects of the crisis were exacerbated by the destruction caused by hurricanes Gustav and Ike, the government decided to restart relations with the EU, which had been disrupted since 2003.

The chancellor, Felipe Pérez Roque, declared that the government of Cuba would make “clear gestures of recognition” of European policies if the EU did not vote in favor of the resolution on Cuba by the UN Human Rights Commission and added that by doing so “Cuba would sign the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on the following day.” In other words, the signing of the covenant would not be predicated on a desire to improve the human rights situation in Cuba. Rather, it was political blackmail, which explains why the signature was never ratified. In the meantime, the chancellors of the EU countries revoked the 2003 sanctions and introduced a “renewed commitment” to the Common Position.

In 2010, Cuba denied entry to the Spanish MEP Luis Yáñez, and the political prisoner Orlando Zapata Tamayo died in a hunger strike. These incidents were condemned by the European Parliament. Deteriorating relations along with internal incidents led to a pledge to free all political prisoners involved in the case of the 75 activists.

In 2014, in response to the release of the political prisoners, the EU authorized the start of negotiations to establish the Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement with Cuba, signed in March 2016 in the presence of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini, and the Cuban chancellor Bruno Rodríguez.

From that moment to the first and second EU-Cuba Joint Council (in May 2018 and September 2019, respectively), there was no progress regarding human rights.

More recently, in June 2021, Cuba’s conduct received three forceful blows that indicate a possily decisive turn:

On the 10th of that month the European Parliament condemned the existence of political prisoners, the persecution and arbitrary detention of dissidents, and insisted that the Cuban authorities release all political prisoners and those who were arbitrarily detained for exercising the freedom of expression and assembly.

On the 20th, in its Annual Report on Human Rights and Democracy in the World, the EU recognized that in Cuba freedom of expression, association and assembly remain subject to important restrictions, and it affirmed that the government of Cuba is not inclined to support the recommendations of the EU member states.

On the 30th, the Lithuanian Parliament, the only country that had not ratified the Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement, upped the ante: It demanded “the unconditional release of political prisoners” and mentioned by name the persecutions of Tania Bruguera, Luis Manuel Otro Alcántara, Maykel Castillo, Denis Solís, Luis Robles and those held as a result of the protest on Obispo Street, among others, and thereupon declared that “it is not politically advisable to ratify the Agreement, effectively nullifying it.

These events have created an unforeseen scenario in Cuba-EU relations.

What lies behind these events was a dismantling of civil society after 1959, the suppression of the most basic civil and political rights, the elimination of private property on the means of production, and the monopoly of the party/state/government over politics, culture, education, and the media.

The current government of Cuba, essentially the same one that debuted in 1959, incurred responsibilities and interests it is prepared to defend. This explains the limited and contradictory nature of its reforms, and at the same time, it reflects its great weaknesses, disguised by impotent gestures and speeches. Within this complex scenario lies the importance of the EU as a partner toward democracy.

“The only thing that can save the Agreement is a public dialogue with civil society and the execution of the European Parliament’s resolution of last June 10th.”

One desirable and beneficial solution to achieve the agenda of the Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement would be to make at least five demands additional of Cuba:

Require concrete actions and not verbal agreements for help, as has occurred since the Common Position was adopted in 1996.

Freedom for all political prisoners, an end to arbitrary detentions, persecution and any other violations of rights and human dignity.

The addition of Cuba to the Covenant of Political and Civil Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights signed in 2008.

The coupling of Cuban law to the United Nations Charter as well as all international instruments of law.

The fomenting of spaces, mechanisms, exchanges, and cooperation with independent civil society in Cuba, establishing direct relations between associations of civil society of both parties without state control.

These minimal requirements, based on Cuba’s needs and on its relations with the EU for twenty-five years, should definitively constitute the lodestar for current and future relations for the good of Cuba, the Cuban people, and the EU.

Translated by Cristina Saavedra

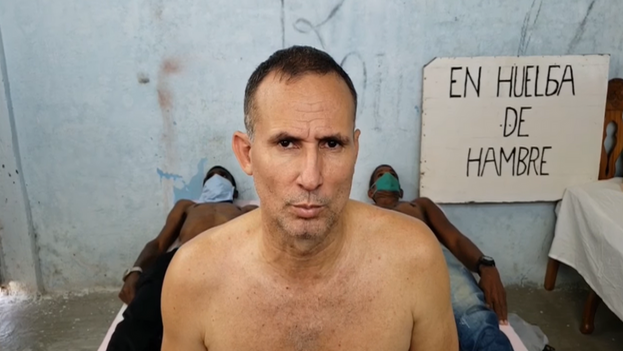

![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 13 May 2023 The Cuban regime remains unyielding with the family of the political prisoner José Daniel Ferrer, leader of the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU), who for the last two months has been denied visits from his wife Nelva Ismarays Ortega Tamayo. After a failed attempt to see him on May 11, Ortega called on the international community and people of goodwill to speak out against the violation of human rights on the island.

14ymedio, Havana, 13 May 2023 The Cuban regime remains unyielding with the family of the political prisoner José Daniel Ferrer, leader of the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU), who for the last two months has been denied visits from his wife Nelva Ismarays Ortega Tamayo. After a failed attempt to see him on May 11, Ortega called on the international community and people of goodwill to speak out against the violation of human rights on the island.