![]() 14ymedio, Sebastián Arcos Cazabón, Miami, 5 December 2021 — Unlike the popular protests of last July 11 and 12, the march called by the Archipiélago platform for Monday, November 15 was announced weeks in advance. The most optimistic put their hopes for rapid change in the march, but they underestimated the repressive capacity of the regime. The most pessimistic criticized the transparency of the announcement, arguing that it gave the regime a chance to prepare, and believed themselves justified when the official repressive deployment kept potential demonstrators at home. To a greater or lesser extent, optimists and pessimists were dissatisfied with the outcome of the announcement.

14ymedio, Sebastián Arcos Cazabón, Miami, 5 December 2021 — Unlike the popular protests of last July 11 and 12, the march called by the Archipiélago platform for Monday, November 15 was announced weeks in advance. The most optimistic put their hopes for rapid change in the march, but they underestimated the repressive capacity of the regime. The most pessimistic criticized the transparency of the announcement, arguing that it gave the regime a chance to prepare, and believed themselves justified when the official repressive deployment kept potential demonstrators at home. To a greater or lesser extent, optimists and pessimists were dissatisfied with the outcome of the announcement.

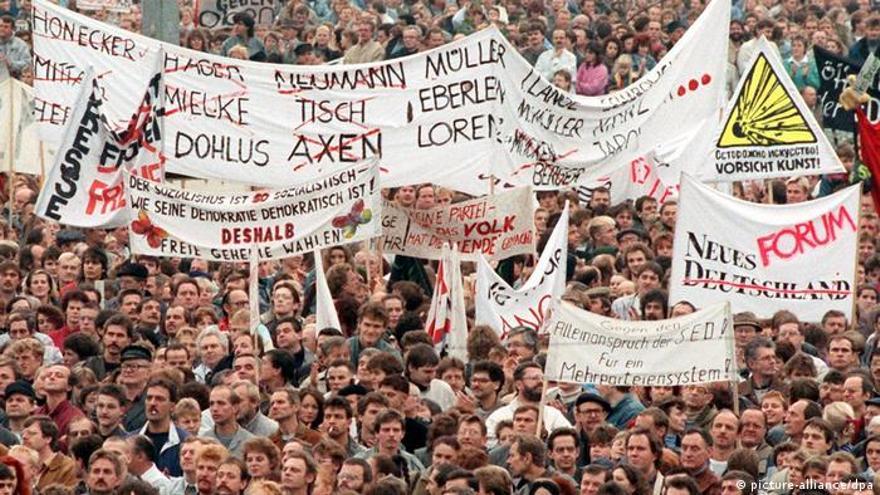

However one looks at it, disappointment with 15N [15th of November] should not be a reason to dismiss organized marches as tools for political change. After all, popular demonstrations played a key role in the fall of all the totalitarian regimes of Europe, and, surprisingly, few were spontaneous; most were planned in advance. To those who claim that Cuba’s circumstances today are different from those of Central Europe in 1989, I remind them that, beyond the peculiarities of each case, they all shared with Cuba the fundamental characteristics of the totalitarian model, with its strengths and weaknesses.

The case of the GDR, the former communist Germany, is sobering for Cuba because I believe the similarities between the two outweigh the differences. Like Cuba today, the GDR in 1989 was ruled by a hard-line Marxist regime with an extensive and brutal internal security apparatus, the notorious Stasi, mentor of the Cuban DSE [Departamento de Seguridad del Estado = the Department of State Security]. In contrast, dissidence in the GDR was mostly limited to Marxist-revisionist criticisms, and never became as openly anti-communist as did Cuba’s, nor did it reach similar levels of public activism, organization, or representativeness. So harsh was the GDR regime that its leader, Erich Honecker, refused to listen to Gorbachev’s calls for reform, and banned the circulation of Soviet publications. In the GDR of 1989, the regime was stronger and the opposition weaker than in Cuba today. continue reading

When Hungary removed the border fence with Austria in May 1989, tens of thousands of East Germans fled that way to West Germany, forcing Honecker to close the border with Hungary and Czechoslovakia, effectively turning the GDR into an island of intransigence in a sea of transitions. Unable to escape, some 1,500 people demonstrated publicly against the regime on Monday, September 4, in Leipzig, the GDR’s second most populous city. Despite the repression, public protests were repeated in Leipzig every Monday in September, attracting increasing numbers of participants. By Monday, October 2, demonstrators numbered more than 10,000.

Honecker threatened a Tiananmen-style massacre if the demonstrators dared to take to the streets again. On Monday, October 9, more than 70,000 people marched in the streets of Leipzig, and the Stasi did not dare to suppress them. The following Monday more than 120,000 demonstrators came out. Two days later Honecker was dismissed and replaced by his second-in-command. The following Monday, 300,000 demonstrators took to the streets of Leipzig. On November 4 the protest moved on to Berlin with more than 500,000 demonstrators. On November 7, the GDR Council of State resigned in plenum, and on November 9, the Berlin Wall fell.

It is likely that the example of what was happening in Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia served as a stimulus for the demonstrators and a brake on the repressive forces. But it is indisputable that, with the exception of the first example, the popular marches that forced the fall of the regime in the former GDR were planned and announced in advance. Unlike its counterparts in Poland and Hungary, the GDR regime had no reformist or revisionist factions, and was united in its reluctance to implement reforms, even economic ones. The Stasi was one of the most efficient repressive apparatuses in the Soviet bloc, and before the September marches they never hesitated to use the most brutal tactics. Despite all this, the courage and perseverance of the demonstrators achieved what seemed impossible.

The 15N convocation was just one of the first of its kind in Cuba — the Ladies in White [Damas de Blanco] and other like-minded groups tried years ago to popularize marches as a tool of public protest. Inevitably, others will have to follow — it took the Germans ten weeks of continuous marches — if Cubans are to rid themselves of Castroism in the short term and with a minimum of violence. Some may fail, and there will be an inevitable cost in repression, but the mere civic exercise of convocation is fundamental and necessary in a country where the state has cultivated absolute hegemony over society for more than half a century. Cubans are beginning to use their atrophied civic musculature, and this civic exercise will give them back the pride and self-esteem necessary to live in a democracy.

Translated by: Hombre de Paz

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.