“It’s been the most difficult decision of my life because I love my career,” says Kirenia, an outstanding student not only in her course but also throughout the University of Medical Sciences of Ciego de Ávila. Her parents supported her from the first moment and encouraged her to leave before obtaining her degree. “I have several classmates who are doing the same thing.”

Kirenia doesn’t know if she will one day be able to graduate as a doctor in Spain, but she will not do so in Cuba. “My grandfather and grandmother are retired doctors and have to work, because their pensions are not enough,” she tells 14ymedio. “Washing dishes in a café in Madrid I can probably live better than them.” continue reading

The winner of many school contests in her teenage days, Kirenia now no longer has a “head for books and studies” because she only thinks about the moment when the plane takes off and she can look from the window at how the lights of the Island move away.

“Since I made the decision, I can’t even sleep. I have the feeling that something is going to happen that is going to stop me from leaving, but my family tells me that I have to calm down and that everything is going to be fine.” Kirenia already announced at the Faculty her decision to leave her career but attributed her departure to a pregnancy and the need to spend more time with her husband and future baby.

However, the truth is that she can’t imagine “working more than twelve hours a day in a hospital where there are no medicines, the toilets are so dirty that many doctors spend their entire day without even urinating, and they earn a little more than 4,000 pesos that don’t serve for much.”

Together with other colleagues they have created a WhatsApp group where they exchange any scholarship opportunity to leave Cuba. “There are more than twenty, most of them are third, fourth and fifth year medical students. If they are given a scholarship, they are willing to leave medical school” and join the almost 200,000 Cubans who have arrived in the United States since last October, or, unspecified, those who have left for other countries.

The Faculty of Medicine has been one of the jewels in the educational crown in Cuba for the last 60 years. The mass graduation of health workers is part of the official policy and is displayed as one of the great achievements of the revolutionary process, in addition to providing doctors to medical missions abroad, one of the main sources for hard currency on the Island.

In six decades, between 1959 and 2019, Cuba graduated 376,608 people in different branches of the Medical Sciences, of which 171,362 were doctors. The number of those who have left their profession to exercise other economically more rewarding professions and those who have emigrated is handled with secrecy, but in hospitals there is often a shortage of qualified staff and specialists.

Artemisa province is a dramatic case: more than 20 medical students from the same year abandoned their studies, all together. “It’s not just to take advantage of Nicaragua’s no-visa policy,” Inés, the friend of one of these deserters, explains to this newspaper. “It’s also because the rumor that they will be ’regulated’ [that is denied permission to leave the country] once they earn the degree is getting stronger, and they are afraid,” she adds in reference to the ban on leaving the country that the Government applies to students who finish strategic careers, such as Medicine.

On the other hand, in the provincial hospital, “several health workers have requested exit permits and, once granted, have emigrated permanently,” says the same source. “Some ask to be discharged; others leave without doing so because they [the authorities] can delay it, and others have taken advantage of gaps in the system; for example, that they’re in their last year of specialty and have not been ’regulated’.”

In the case of Yander, age 24, the reasons for requesting dismissal from the Victoria de Girón Faculty of Medical Sciences, in Havana, were different. He entered the first year of the program a few months before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. All students were, in one way or another, sent to support hospitals in the face of the large avalanche of people infected with the virus.

“I had hardly any experience and I had to face situations that I don’t want to live through again,” he tells 14ymedio. “The main problem for me was not the fear of getting sick; I got infected twice. I also didn’t make this decision from seeing so many people die without being able to do much to help them, because even oxygen was scarce.”

Yander got tired of the health authorities using students and recent graduates “as if they were furniture… Nobody was asking us anything. They moved us back and forth to support here and there, but the conditions in which we worked were terrible. There was a week that I could only eat bread with something and a juice that I don’t even know what it was because it only tasted like water with sugar.”

“The situation of doctors is something that you have to experience to see.” The young man decided to end his career as a doctor on the day that “a companion was upset because his mother with cancer was dying, and we didn’t even have a painkiller to give her. The man assaulted me and a nurse with a chair.” That night, when he returned home, Yander hung up his white coat for good.

He now has a business selling birds in Cerro. “What I learned at the Faculty I use a lot in the care of these animals, and I also sell hamsters, turtles and rabbits, in addition to the food they need.” The days when business goes badly, Yander still earns what a doctor achieves in a week. “I don’t miss it at all; rather I feel that I was saved from disaster.”

Economic problems also tipped the balance for Nelson Sánchez Ramos’ daughter. “We decided that the best thing for our daughter is to abandon her studies,” this man wrote on his Facebook account. “The disparity between what a professional earns who must study six years to save lives and what the frontmen of the regime receive, makes you reflect on your future and the future of this country.”

Sánchez’s wife, a graduate of Medicine, ” was forced to stop practicing the profession because it’s very difficult for her to get used to living on a salary” that doesn’t even guarantee a regular breakfast. “My girl lost motivation for her studies and now she has to make a huge effort as many university students in this country do, to graduate from a profession that they may abandon in the future to be able to fulfill their dreams, or for something as basic as guaranteeing an adequate diet for her and her children.”

Wage contrasts are obvious between what a doctor earns and what the members of the Ministry of the Interior earn. “Cubans interested in training as prison officials will receive 6,690 pesos of monthly salary, after a course of five and a half months, while a newly graduated doctor earns 4,610 pesos; a resident studying his specialty receives 5,060; and in the case of doctors with finished specialties, the salary ranges between 5,560 and 5,810,” concludes Sánchez.

Others abandon their studies to use all their energies to leave the country. “My son left Medicine in his fifth year and sold everything he had to pay for the ticket to Nicaragua. He has already been in the United States for three months and works in a brigade of builders. His friends at the Faculty see him as a hero,” says Frank Vilaú, father of a 26-year-old boy. “Now he is earning enough to help his girlfriend, who also left medical school, to get out of Cuba.”

But the exodus is not only happening in university education and, specifically, in the faculties of Medicine but also at all educational levels. René, a 45-year-old father from Havana and about to leave for the United States with his children through the family reunification program, visited the youngest’s high school to communicate to the teacher that the child would no longer continue attending classes because of the imminent departure.

“The teacher almost burst into tears and told me: ’No one is going to be left here. I have several students who are in the same situation, and other teachers have also told me that the same thing is happening in their classrooms.’”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.

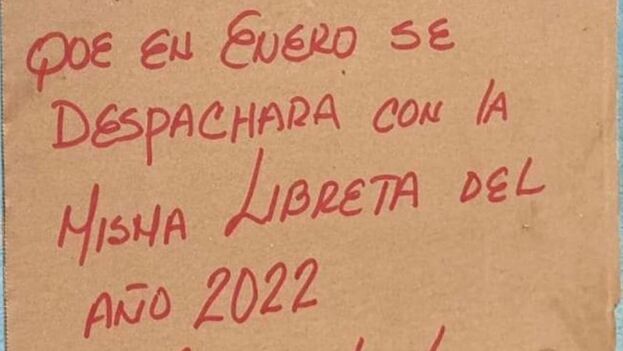

![]() 14ymedio, Natalia López Moya and Juan Diego Rodríguez, Havana, 29 December 2022 — “Customers please be aware that in January we will be using the same ration book as 2022. So please look after it!” Messages like this one, written hurriedly on a scrap of cardboard and stuck carelessly onto the shop door, have been appearing in numerous stores in Cuba over the past week.

14ymedio, Natalia López Moya and Juan Diego Rodríguez, Havana, 29 December 2022 — “Customers please be aware that in January we will be using the same ration book as 2022. So please look after it!” Messages like this one, written hurriedly on a scrap of cardboard and stuck carelessly onto the shop door, have been appearing in numerous stores in Cuba over the past week.