In a recent conversation during an evening visit to a friend of my generation (let’s call him Michael) I had a revelation that surprised me: “I’ve never been able to overcome the oppression that stirs in me on Sundays.” I inquired about the reason for the strange rejection for a holiday that’s usually shared with the family at home, and he explained. Every Sunday, from the time I was 11 until I was 17, he was forced to return to his intern camp, a kind of boarding school in the countryside. Sunday was thus engraved in his memory as the day that, inexorably, reluctantly, one moved away from home and his parents, grandparents and younger siblings, with a hanger in one hand, where an impeccably laundered uniform hung, having been washed by your mother, with a plastic garment bag over it to protect it from dust. In the other hand, the schoolbag –when you opened it, already at the camp’s ugly dorm- the familiar smell of a steak sandwich would escape, which motherly care had placed there to ease your hunger and comfort you in your separation, at least on that Sunday night.

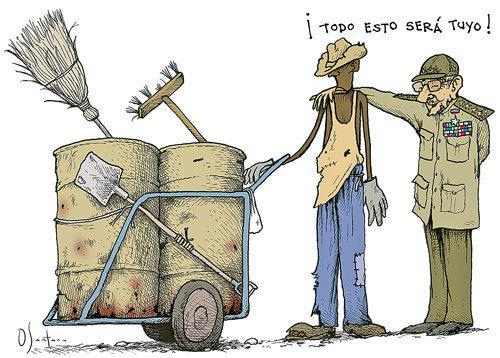

In a recent conversation during an evening visit to a friend of my generation (let’s call him Michael) I had a revelation that surprised me: “I’ve never been able to overcome the oppression that stirs in me on Sundays.” I inquired about the reason for the strange rejection for a holiday that’s usually shared with the family at home, and he explained. Every Sunday, from the time I was 11 until I was 17, he was forced to return to his intern camp, a kind of boarding school in the countryside. Sunday was thus engraved in his memory as the day that, inexorably, reluctantly, one moved away from home and his parents, grandparents and younger siblings, with a hanger in one hand, where an impeccably laundered uniform hung, having been washed by your mother, with a plastic garment bag over it to protect it from dust. In the other hand, the schoolbag –when you opened it, already at the camp’s ugly dorm- the familiar smell of a steak sandwich would escape, which motherly care had placed there to ease your hunger and comfort you in your separation, at least on that Sunday night.“I can’t help those sad memories when I see the students now, going, hangers and uniforms in hand, toward the pick-up stops. Every time I think about all the time they stole from me, in the compulsory removal from the family, the sacrifice that was made because they told us that if we studied hard we would have better lives, and that where you could really study was at the camp schools, with a perfect educational system, I feel an unbearable impotence. “

I was never an inmate in these boarding schools because I was born several years before my friend and was able to attend urban schools through middle and high school, tried to imagine a child’s feelings at the onset of his adolescence, separated from his elders just when he needed them the most. In my case, I had to attend the Escuelas de Campo**, but at least my stays were relatively brief, though the conditions were those of a forced labor camp, promiscuity in the dirty sleeping quarters and even dirtier latrines. Michael stayed long stretches at the academic internships of the revolution for six whole terms. My friend tells me that he spent those weeks dreaming about Saturday’s arrival –classes were held from Monday through Saturday back then- when the “pass” at noon would commence and he would soon be in his bed, in his room, finally enjoying the privacy of a clean bathroom, his mom’s seasonings and of his family’s love and protection.

I allow my friend’s mind to reminisce: “I was one of those innocent kids, still playing with toys. My uncle had brought me an electric train from the German Democratic Republic which I was never able to enjoy sufficiently because I was away at the boarding school. I spent the week among those delinquents of all backgrounds, pretending to be fearless and repeating profanities and bragging with vulgarities never uttered at home. It was a way to survive the internship because we were all a mixture of those from decent and functional families next to the ones on the edge, offspring of violent homes, of alcoholic or criminal parents. If you put it in perspective, the camp schools were jungles where the weakest perished, victims of bullying and hassling by the abusers. If you became a softie, you would be slapped around, in the best of cases. In the dorms, a prison attitude reigned, with gangs and social castes clearly established. Dorms and bathrooms were the more dangerous places, because there was less policing and control from the teaching staff.

What always saved me was this tough armor God gave me, because you had to think twice before messing with me, but, in truth I was always a quiet kid who avoided problems. I had been brought up in a harmonious family environment and was very polite. Those six years were traumatic for me. However, I never commented on it at home, because I did not want my parents to worry. While at the internship camps, I pretended to be another fearless kid. At home, I pretended to be happy at the camps. When you spend your adolescence that way, there comes a time when you don’t know deceit from truth in your life. You create a kind of armor and distance yourself from your family because you learn to survive without them and, since they are not around you at the worst moments, you make do without their help and advice. When I finally finished the internship stage and returned to bosom of the family, I had changed. It’s as if something dear from your past had broken beyond repair. That’s what I sense in me when I remember those days: a sense of uprooting, of loss, of doom.”

Miguel speaks fluently. He is a qualified and intelligent man. I have transcribed here an approximate reconstruction of his conversation, which I did not record (conversation between friends is never recorded, of course), but he can attest to the accuracy of my portrayal of his personal experiences and memories. I know many adults who received these “scholarships” in their teens, but few recognize as sincerely as he does the deep tracks that experience left in their lives. It usually happens to those who suffer from rape or assault, women abused by their husbands, or other humiliating events, whose damage victims rarely openly acknowledge, as if, somehow, they were guilty, as if talking about it constituted a sign of weakness or made them involuntary accomplices of their tormentors for bringing out memories that they would prefer to keep buried. There are even some interns who tell the story of their experience as a cheery and happy time, as the best thing that could have happened to them. Those individuals are not even aware of what they lost. Personally, I think you have to live in a very hostile or repressive home to prefer an internship; I can’t but sympathize with those who found the separation from their family their better option.

To end the topic, Miguel smiled, part accomplice, part mischief. The nature of Cubans drives them to joke even about things that cause pain: another way of coping we have learned. “You know what? I assure that there were two Pedro Pan Operations: the interim plan that separated 14,000 children from their parents to send them to the US and the one that has been separating hundreds of thousands of families for decades to send them to government camp schools. I can’t tell which one is worse, but I’m inclined to think that the one here is.”

I think I agree with him.

Translator’s notes:

*”Operation Pedro Pan” was a program by which thousands of Cuban children were sent to the United States in the early years of the Revolution, without their families, as a way to get them out of Cuba. Many of the children had extended family in the United States, and/or were reunited with their families when their parents later made it to the United States.

**Escuelas en el Campo — Schools in the Countryside — was a shorter program where students went for a small part of each year, to similar boarding schools where they studied and worked in agriculture.

Translator: Norma Whiting

May 28 2012