![]() 14ymedio, Jacobo Machover, Paris, December 17, 2023 — Sad and terrible realization: Cuba leads the most virulent anti-Semitism in much of the world, outside Arab and Muslim countries. The most rancid insults to Israel and the Jewish people are pronounced without the slightest embarrassment by Mariela Castro, the daughter of Raúl Castro; Aleida Guevara, daughter of the Argentine guerrilla and murderer Ernesto Che Guevara; and the puppet president Miguel Díaz-Canel, hand-picked by Raúl Castro.

14ymedio, Jacobo Machover, Paris, December 17, 2023 — Sad and terrible realization: Cuba leads the most virulent anti-Semitism in much of the world, outside Arab and Muslim countries. The most rancid insults to Israel and the Jewish people are pronounced without the slightest embarrassment by Mariela Castro, the daughter of Raúl Castro; Aleida Guevara, daughter of the Argentine guerrilla and murderer Ernesto Che Guevara; and the puppet president Miguel Díaz-Canel, hand-picked by Raúl Castro.

Cuba doesn’t even try to hide the anti-Semitic feeling behind an “anti-Zionism” that condemned the State of Israel but not all the Jews. Proof of this is the statement of Aleida Guevara in a video broadcast in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, where she went to offer her services with her own program to a television channel close to the Islamist terrorist organization Hezbollah: “Today you [Israel] are becoming the worst of humanity. Is that what you want for the new generations? Is that what you want to be remembered for in the world as a people of Israel and a Jewish people?”

Note that “let it be remembered” means, delicately, that these people do not have the right to exist, without distinguishing between the Jewish State and the diaspora scattered around the world. Aleida follows in the footsteps of her father, a doctor who liked the taste of blood more than the vocation to heal his fellow human beings: “I am a pediatrician and I can act. There is no problem at all. But on top of that, I’m a pretty good shot. I have a good aim and am militarily trained, because I come from a military school. Therefore, I am at your disposal.” continue reading

She doesn’t even try to hide that anti-Semitic feeling behind an “anti-Zionism” that condemns the State of Israel but not all Jews

Guevara’s daughter, the imposing and unpresentable Aleida, therefore incites people, using her still mythologized surname, to armed “resistance” against Israel, without the slightest reference to the infamous massacre perpetrated on October 7 against young people who were celebrating and pacifists from Israel and all parts of the world. She doesn’t mention her buddy and close friend, Mariela Castro Espín, daughter of Raúl and niece of Fidel, a “deputy” in the National Assembly of People’s Power (yes, like her), who has a reputation for being more liberal than other leaders in Cuba for “defending” the homosexuals, once persecuted mercilessly by her uncle and father.

Aleida also advocates the use of weapons against “imperialism” (Zionist, of course): “The Intifada has symbolic value in the Palestinian resistance, but imperialism can no longer be confronted with stones, nor with words, nor by diplomatic channels.” As for Díaz-Canel, it should be noted that he personally attended a demonstration of Palestinian “medical students” in Cuba (who also follow an ideological and military formation, like all foreign “students” in Cuba).

The small Jewish community that remains on the Island (the vast majority went into exile in the years following the revolution) had the courage to protest against the words of Mariela Castro, remembering the victims of October 7 and the hostages who still remain in the hands of Hamas, Islamic Jihad and other Palestinian terrorist groups such as the FPLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine), allies of Castroism.

The small Jewish community that remains on the Island had the courage to protest against the words of Mariela Castro

The terms of its protest have nothing to do with the belligerent speeches of the government leadership: “We regret and feel the pain of every child, woman, man, every innocent person who dies in this war against terrorism, not only because of the war but also because of being forced into war zones as human shields of Hamas.” After decades of being reduced to silence and tacit approval of government policy, the Jewish community has finally reacted.

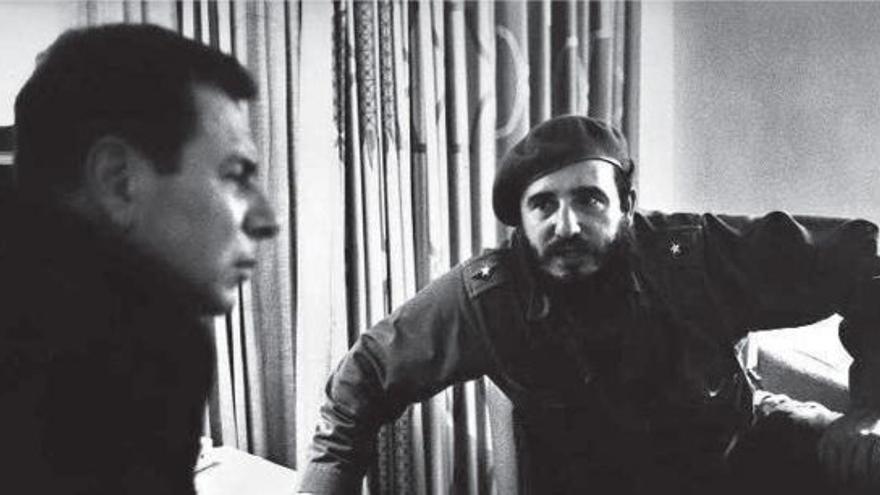

The Castro-communist regime’s support for the attempts to make Israel disappear from the map is not new, and not just with words. In 1973, the Castro brothers sent troops to Syria, the country of Hafez Al-Asad, father of the current butcher-dictator of his own people, to fight Israel at the time of the Yom Kippur war, as well as military instructors to the Palestinian camps of southern Lebanon, while thousands of fighters (often presented as “students”) were trained on the Island. And in international forums, Cuba was (and continues to be) in the front row to condemn Zionism as “racism,” at the head of all anti-imperialist countries.

However, Fidel Castro, almost at the end of his life, criticized the then Iranian president Mahmud Ahmadinejad for wanting to eradicate Israel from the face of the earth, believing that the Jewish people were the ones who had suffered the most in the history of the world, while his half-brother Raúl Castro officiated at a synagogue in Havana, lighting a candle during the celebration of Hanukkah … intimate contradictions of the great dictators…

One of his disciples, the Venezuelan commander Hugo Chávez, followed the example of his Cuban mentors, vomiting his sinister diatribe in 2010, following an Israeli attack on “humanitarian” ships that were heading towards the territory of Gaza, controlled since 2005 by Hamas: “I take the opportunity to condemn again from the bottom of my soul and my viscera the State of Israel. Damn you, State of Israel. Damn you. Terrorists and murderers. And long live the Palestinian people. Heroic people, good people.”

It should be noted that all those who support the Hamas terrorists are mostly the same as those who support Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine

The late Chávez did not know how to control himself, opposing the “good” Palestinians against the “bad” of Israel. As did Maduro, the Colombian Petro, the Chilean Boric, the Bolivian Arce, the Nicaraguan Ortega, the Brazilian Lula, the Mexican López Obrador, the Argentines Fernández and Fernández de Kirchner, already replaced by Javie Milei, whose position on the conflict is radically different from that of his predecessors, in proclaimed support of Israel.

It should be noted that all those who support the Hamas terrorists are mostly the same as those who support Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine, led by its admirable Jewish president Volodimir Zelensky, who is on the side of Israel and its people, a democracy like Ukraine, despite the current government of Benyamin Netanyahu, held hostage by some of his ministers, the ultra-orthodox religious, and his guilty ineffectiveness in defending his citizens on that atrocious day of October 7. Netanyahu’s power is now, however, limited by the members of the “War Cabinet,” in which his centrist opponent, General Benny Gantz, is prominently featured.

Who knows what can arise from the horror, this time caused by the killing of Jews and also by the Israel Defense Forces’ offensive that causes infinite civilian deaths? Some attempt at peace? It was the case after the Yom Kippur war thanks to the agreement with Egypt, then led by Anwar Sadat, assassinated by the Muslim Brotherhood; of the Gulf War of 1991, which gave rise to the Madrid conference on the Middle East; the first step towards the Oslo Accords of 1993, signed by Yitzhak Rabin, Shimón Peres and Yasser Arafat, under the impulse of Bill Clinton; or after the transfer of the American Embassy to Jerusalem, by the Abraham Accords with several Arab countries, driven by Donald Trump and his son-in-law Jared Kushner.

It only remains, in this black period for the history of humanity and for the conscience of free men and women, to take up the words of Rabin, killed by an Israeli extremist in 1995, as a cry of hope: “Enough blood!”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.