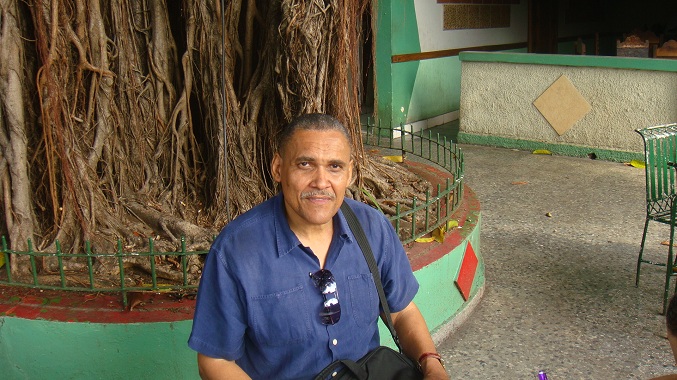

For someone from Havana, the best thing is to walk the streets in spring. These March days, Jorge Olivera Castillo, 52, poet and journalist, is delighted by the green of the trees, the salty aroma, and the gentle sun.

On any weekday morning, he traces his own journey. Aimlessly wandering through a maze of alleyways crammed with the facades of propped up tenements: in these sites reside in the subjects of his stories and poems. He likes to walk the streets of Central Havana, and places not on the tourist postcards.

It was in another spring, that of 2003, when the State wanted to break a handful of peaceful men and women, making arbitrary use of its absolute power. And sentences were handed out to Cubans, like Jorge Olivera, who disagreed and disagree with a regime that confuses a nation with a farm, and democracy with loyalty to a commander.

Olivera was one of 75 prisoners of the Black Spring. Ten years later, without drama, he recalls those days. “About two o’clock in the afternoon of March 18, 2003 I was arrested. I had returned from the hospital, to be seen for a gastrointestinal problem, when a troop of about twenty violent soldiers appeared. At that time I was director of Havana Press, an independent press agency. They conducted a thorough search of every piece of paper I had. They seized books of literature and my stories and articles. An old Remington typewriter. Family photos, letters from friends, electric bills and even my phone bill. A clean sweep. Everything was confiscated by state decree.”

When a government says that a man who writes must be prosecuted, something is wrong with this society. The weapons of free journalists like Jorge Olivera, Ricardo Gonzalez, Raul Rivero and other reporters sentenced to 24 years in prison, were the words, typewriters and landline telephones through which once a week they read the news and their texts about the other Cuba the regime tries to ignore.

In April 2003, a Summary Court sentenced him to 18 years’ imprisonment. “The trial was a circus. Without legal guarantees. The defense attorneys were more afraid than we were. The definitive evidence showing that I was a public threat were my scattered internet writings and recordings of my participation in programs of Radio Martí,” says Jorge.

He slept 36 nights in Villa Marista, headquarters of the secret police, a former religious school transformed into custody for opponents. Located in the Sevillano neighborhood, in the 10 October municipality, Villa Marists is a left over from the Cold War. A Caribbean imitation of Moscow’s Lubyanka Prison from the Communist period. In March 1991, He was there thirteen days, accused of ’enemy propaganda’. When you enter the two-story building, with walls painted bright green, a watch officer sitting behind glass receives you.

They use techniques of intimidation and psychological torture. You’re not a human being. You become an object. A property of special services. Before a gray dress uniform they undress and humiliate you in front of several officers. They force you to do squats and open your anus. As in Abub Ghraib or imprisonment in Guantanamo Naval Base. But in Cuba it has been applied much earlier.

“They were terrible days. In the cells minimum of four people were boarded. The beds were a zinc plate fixed to the wall with a chain. The medicines are placed on a ledge outside the cell. You are called by a number. I was not Jorge, but the prisoner 666. You sleep with two light bulbs that never go off. At any time of day or night you can be called for lengthy interrogations. They lead you through long and gloomy passageways of packed cells where you do not see any other detainee. It’s like being in the mouth of the wolf,” says Olivera.

Some dictators often have a macabre sense of humor. After extensive tortures, Stalin used trials and self-incriminations as a spectacle. Sometimes there was no show. They put your back to a wall and gave you one shot to the temple. If they wanted to prolong the agony and break as a human being, they sent you to a Gulag.

In Cuba, the agents of the State Security have modeled these methods. Except the shot to the temple. One of those strokes of ridicule that the repressive apparatus of the Castro likes, Olivera keeps fresh in his memory. The condemned of the Black Spring were spread out among the island’s prisons in comfortable air-conditioned coaches, the same ones used for tourists.

“The height of cynicism. We traveled that day watching movies and they gave us good food. We were treated like royalty as we deposited in prisons hundreds of miles from our homes. I was detained in Guantanamo Provincial Combined, six hundred miles from where my wife and my children live,” he recalls.

The worst experience Jorge Olivera lived through was the prison. “The food was a mess. Officers beating common prisoners in common. Inmates self-mutilate. Or commit suicide. Poetry saved me from madness.” It was in prison where Olivera began writing poems. In 2004, due to a string of illnesses, he was granted a parole.

Technically he is still not a free man. If the government decides, the Black Spring prisoners remaining in the island can go back behind bars. Of the 27 independent journalists imprisoned in March 2003, Jorge Olivera is the only one left in Cuba. Abroad he has published four books of poetry and two of short stories.

Right now he gives shapes to his latest poems. “Systole and Diastole”is the working title. He writes for Cubanet and Digital Spring, a weekly where for six years the best independent journalists have performed.

Along with fellow journalist Víctor Manuel Domínguez, he leads a writers club. He is an honorable member of the Pen Club of the Czech Republic and the United States. If people could receive a grade for the human condition, I wouldn’t hesitate to shake his hand to give a ten to Jorge Olivera. His priorities remain information, describing the reality of his neighbors in Central Havana, the crisis of values, prostitution and official corruption.

The author of “Surviving in the Mouth of the Wolf” rejects the ’amnesia’ of newly minted dissidents. “You can not forget history. The rebellious generation that dominates the new technologies is welcome. But they should be honest and admit that before them, we were there. Looking at news on hot news and under constant police harassment. We did not have Twitter or Facebook, we wrote with pens on the back of recycled paper. But we never stopped reporting on the precarious life and lack of a future for the people in Cuba. That can not be relegated or forgotten. The history of dissent is very long. And before us, were those who were sentenced to death in La Cabaña. If we forget these stages, mutilate or distort an important part of the peaceful struggle against the Castro regime,” says Jorge Olivera.

His dream is to do radio, be healthy and live in a democracy. He hopes the day is not too far off when he can reunite with Raul Rivero and Tania Quintero, two fellow exiles. Not in Switzerland or Spain, but walking the streets of Havana in the spring.

Iván García

31 March 2013

Fifty years ago, on May 10, 1960, the Matamoros Trio, headed by Siro Rodriguez, Rafael Cueto, and Miguel Matamoros, performed in public for the last time. They bid their farewells on the program called Partagas Thursdays, one of the most popular Cuban TV shows at the time.

Fifty years ago, on May 10, 1960, the Matamoros Trio, headed by Siro Rodriguez, Rafael Cueto, and Miguel Matamoros, performed in public for the last time. They bid their farewells on the program called Partagas Thursdays, one of the most popular Cuban TV shows at the time.

When I first went to his home, what struck me most was an old glass cabinet. Inside, sorted by date, were national newspapers from at least ten years before.

When I first went to his home, what struck me most was an old glass cabinet. Inside, sorted by date, were national newspapers from at least ten years before.

Carrying out any sort of political analysis or political prediction in Cuba is almost like an Indiana Jones adventure. The media does anything it can to misinform. They barely extract any bit of information from those in power. There is no way of getting any official statistics or facts.

Carrying out any sort of political analysis or political prediction in Cuba is almost like an Indiana Jones adventure. The media does anything it can to misinform. They barely extract any bit of information from those in power. There is no way of getting any official statistics or facts.