In the 1960s, close to 30,000 young men were detained in forced-labor camps. The mistreatments that took place in these camps, known as Military Units to Aid Production UMAP, in the name of “social hygiene,” testify to the homophobic component of the Cuban Revolution.

Abel Sierra Madero, From Letras Libras, January 2016 — Between 1965 and 1968, the Cuban government established, in the central region of the country, dozens of forced-labor camps known as Military Units to Aid Production (UMAP), where about 30,000 men were sent under the pretext of the Obligatory Military Service Law (SMO). The hybrid structure of work camps cum military units served to camouflage the true objectives of the recruitment effort and to distance the UMAPs from the legacy of forced labor. Thus the military-style organization and discipline to which the detainees were subjected could be justified. November 2015 marked 50 years since the regime implemented this experiment.

Historians have generally avoided research into state social-control policies based on forced labor, concentration and isolation of thousands of Cuban citizens at rural locations set up during the 1960s. Likewise, they have rejected the usage of such terminology, as if it did not apply to the case of Cuban socialism, or its use was not “politically incorrect.” By the same token, testimonies and narratives produced by former UMAP detainees have almost always been held suspect. A fascination with beards and uniforms on the part of the mainstream press in Europe and the US, along with powerful images constructed by revolutionary propaganda, have up to now overshadowed the testimonies of Cuban exiles regarding their terrible experiences in these camps.

These accounts became part of an anti-communist narrative to which, supposedly, the exiles had to conform in order to survive outside Cuba. At least, that was what Ambrosio Fornet, one of the most recognized intellectuals on the Island, thought in 1984 while giving an interview to Gay Community News. Although he recognized that the UMAPs were a sort of “academy to produce macho-men,” Fornet criticized the perspectives on the repression offered by exiled Cuban writers and artists in the documentary film, Improper Conduct (1984), by Néstor Almendros and Orlando Jiménez Leal. According to Fornet, the majority of the witnesses who appeared in the film lied about UMAP; the writers were saying “what they should say because they’re making a living off of anti-communism.” He added, “The idea of a repressive police state that persecutes individuals is totally absurd and stupid.”

UMAP cannot be understood as an isolated institution, but rather as part of a project of “social engineering” geared toward social and political control. That is, a technology that involved the judicial, military, educational, medical and psychiatric apparatuses. For the establishment of these camps, complex methodologies were employed to identify specific subjects and purge them from mass institutions and organizations, up to and including their recruitment and internment.

Masculinization and Militarization

There were several criteria that the authorities took into account to recruit and intern thousands of subjects in the forced-labor camps. One of them was homosexuality, and it is estimated that around 800 homosexuals were shut away in the camps. Nevertheless, there were other, political, reasons.

In the mid-1960s, Cuba was involved in a transnational process of constructing socialism along with the Soviet Union, the Eastern socialist bloc, and China. These regimes invested many symbolic resources in the creation of national stereotypes that were almost always associated with complex processes of masculinization. In this sense, the concept of the “New Man” was one of the most powerful ideals within these systems, although it had also been used by German Nazism and Italian Fascism.

In the Cuban case, this concept was associated with a broader ideological strain of social homogenization in which fashion, urban sociability practices, religious creeds and work-related behavior were key elements to bring in line with the official normative vision. Thus it is not strange that—besides homosexuals—delinquents, religious believers, intellectuals or simply young men of bourgeois background, were also sent to UMAP.

Although the establishment of the forced-labor camps was accomplished towards the end of 1965, these camps were created under the pretext of Law 1129 of 26 November 1963, which established Obligatory Military Service (SMO) for a period of three years, for men between the ages of 16 and 45. The law exempted those who were the only source of economic support for their parents, spouse and children. At least in theory, the law allowed for a deferral of the recruitment of young men who were finishing their final year of secondary school, pre-university, or university studies.

Nonetheless, the authorities applied those sections with discretion, employing political criteria regarding UMAP. Some young men who constituted the only support for their families were recruited without regard for the consequences for those domestic economies. Many students of diverse educational levels who were at the point of graduating became eligible for recruitment to the SMO when they were expelled as part of a “purification” process. This process, which began around 1965—a few months before the first call to UMAP—had the character of a “purge,” a social crusade, headed by the Union of Young Communists (UJC) against those who were not perceived as “revolutionaries.”

In a communication published in Mella magazine on 31 May 1965, the UJC admonished high school students to expel “counterrevolutionary and homosexual elements” from their groups in the final year of study, so as to impede their university admissions. Also mentioned are those who display “deviances,” or “some kind of petit-bourgeois softness and apathy towards the revolutionary activities being performed by the student body.” They should be sent to the SMO so that they may “gain the right” to be admitted to university. “You know who they are, you have had to fight them many times […] apply the strength of worker and peasant power, the strength of the masses, the right of the masses against their enemies […] Away with the homosexuals and counterrevolutionaries from our schools!” Thus concluded the communication.

A few days later, Alma Mater magazine—the official organ of the Federation of University Students (FEU)—went along with this policy, assuring readers that the purification was the result of the historical moment, and a “necessity for the future development of the Revolution.” The assertion was that the purges of counterrevolutionaries and homosexuals should not be understood as two isolated processes, but rather as one, because “so noxious are the influence and activity of both of them to the formation of the professional revolutionary of the future.”

Once the purges were finalized, those young men were left exposed and at the mercy of the State. Their entry into UMAP was a matter of time. No sooner were the purifications concluded, via the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR)—one of the most effective surveillance institutions created for social and political control in Cuba—than censuses were conducted to identify those youths who were not working nor going to school. This information was provided to the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Revolutionary Armed Forces (MINFAR), the entities charged with recruitment for the UMAPs.

By 1964, Fidel Castro was boasting of the impact the SMO was having on Cuban youth, and emphasizing the failure of institutions such as the family and school in the education of young people. “All right, then, what they could not teach them at home,” he would declare, “what they could not teach them in school, what they could not teach them at the institute, they learned in the army, they learned in a military unit.” For his part, his brother Raúl Castro Ruz, at that time minister of the FAR, gave assurances in a speech delivered on 17 April 1965, that the objectives of the Revolution could only be achieved with a “youth of tempered character,” possessing a “firm character” that was “forged in sacrifice,” far from “softnesses.” A youth that would be inspired “not by dancers of the Twist and Rock and Roll, nor by a display of pseudo-intellectualism,” a youth that would stay away from “all that would weaken the character of men.”

The economic utilization of the body

By way of these processes of militarization and masculinization, the intent was not only to correct gestures and postures, but to reorient and reintegrate those forces and bodies to an economic apparatus. The rhetoric of war, employed repeatedly by the leaders of the Revolution, was incorporated into the ideological and economic discourse in the form of military-type campaigns, and the workers were seen as heroes and soldiers—not just to insert them into a political rituality, but to utilize them as a workforce without having to compensate them financially. In a 1969 article, economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago analyed the types of non-paid work during the 1960s in Cuba, and among those models mentioned UMAP. According to Mesa-Lago, the government achieved savings of around $300-million Cuban pesos through non-paid labor between 1962 and 1967.

Around the 1960s, the Cuban economy was dependent on sugar, but the mechanization of cane-cutting was not widespread, therefore the success of the harvests depended on manual cutting. During this period, the sugar harvests began to form part of a great ideological leap that Fidel Castro had planned for 1970. The Maximum Leader was trying to take the Island to a higher degree in the construction of socialism by way of a harvest of ten-million tons of sugar. To achieve the desired effect, Castro needed to mobilize and deploy a major workforce to the areas where large sugar plantations were located. Camagüey province, with considerable expanses of land and scarce labor, was strategically selected for the establishment of the UMAPs in the final months of 1965.

Thus, the camps were inserted into the planned socialist economy, as had occurred in the Soviet Union with the gulag (General Directorate of Labor Camps). Vladimir V. Tchernavin, who managed to escape from a Soviet gulag, describes how, at the start of 1930, that institution became a great forced-labor enterprise, appearing to be a correctional entity, which allowed for the establishment of development plans in places where such an endeavor would have been very difficult without the available forced labor. According to Tchernavin, the gulag provided a structure and functions similar to those of a state enterprise, it was organized like military units, and the detainees received a miserable wage for their work.

A similar thing occurred with UMAP. The inmates of these camps, as well as others recruited by the SMO, received a salary of seven pesos per month, and they were compelled to participate in what is known as “socialist emulation,” a type of competition to incentivize production in which the “vanguards” did not receive financial compensation, but rather diplomas or recognition during political and mass events.

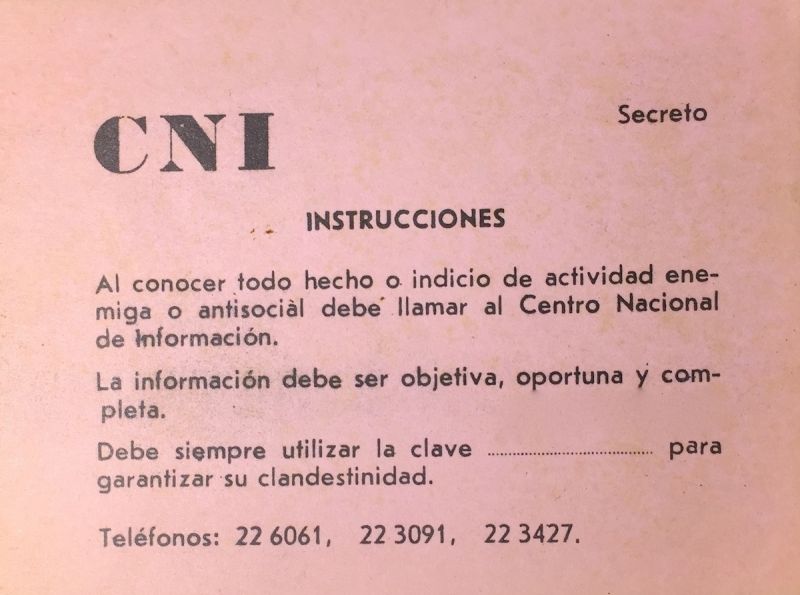

![Cover of Sin Tregua! [Without Truce], informational bulletin of the UMAPs political arm, No. 6, 1967. “Social hygiene is what this is called”](https://translatingcuba.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/umap-6-6.jpg)

It could be said that at the start of 1959, moral panic was the ideological framework on which the campaign for national regeneration was based, which called the entire nation to liquidate the “vices” of the past and consolidate revolutionary power. But very soon, this religious sort of schema was complemented with speeches about hygiene and the notion of “social sickness.”

On 15 April 1965, some months before the first recruitment drive for the UMAPs, the writer Samuel Feijóo, in El Mundo newspaper, published “Revolution and Vices,” an account of the tensions that caused the merging of the religious, political and hygienic discourses. Among the vices that still needed to be eradicated, the writer pointed to alcoholism, and “rampant and provocative homosexuality.” He assured readers that the matter was “not about persecuting homosexuals, but rather about destroying their positions, their procedures, their influence. Social hygiene is what this is called.”

In this manner, the discourses on hygiene and those that came out of the field of psychology were adapted to justify the UMAPs. The camps became a quarantine area, a laboratory that provided not only for the isolation of inmates, but also for the opportunity to study them. In May of 1966, a few months after the UMAPs had been established, María Elena Solé put together a team of psychologists and physicians that made up a secret operation organized by the political arm of MINFAR, to design and work on rehabilitation and reeducation programs for homosexuals in UMAP.

According to Solé’s testimony to me in March 2012, the team’s work consisted in “evaluating these persons from a psychological perspective.” But the evaluation and classification was not based exclusively on aspects related to the generic-sexual configuration of the individuals, but rather incorporated also an ideological criterion.

The team of psychologists drew upon the notion of “afocancia,” a cubanism not recognized by the dictionary, which has been employed to negatively describe those persons who stand out publicly because of certain physical or moral characteristics. Thus, a Template A (for “afocante”) was designed, to distribute homosexuals across four scales: A1, A2, A3 and A4. Type-1 “afocantes” were considered to be those “who did not make a public show of their problem, and were revolutionaries—in the sense that they did not wish to leave the country—comported themselves in a normal fashion, and were more or less integrated into society.” Conversely, “one who let his feathers fly and who, besides, was not integrated into the Revolution nor had any interest in it,” and had expressed a desire to leave the country, was considered a Type-4 “afocante.” As María Elena Solé explained, “there were revolutionaries in this group, but if someone made a display of his problem, we would not classify him as A-1, but as A-4.”

Some of the former UMAP inmates assure me that the team of psychologists conducted various experiments and tests of a behaviorist and reflexologist nature, which included the application of electroshock. However, Dr. Solé asserts that the tests that were done were solely designed to “measure intelligence.” In contrast, Héctor Santiago — a theater person connected to one of the most controversial cultural projects of the 1960s in Cuba, Ediciones El Puente, and who was sent to a UMAP — assured me that the team’s examinations were, at least in their totality, of another character. According to Santiago, the psychologists and psychiatrists utilized behaviorist techniques in the UMAPs such as shocks produced by electrodes, and insulin-produced comas. These experiments consisted in the application of alternating-current shocks “while showing us photographs of nude men, so that we would subconsciously reject them, turning us by-force into heterosexuals.”

This description concurs with various articles that detailed this procedure and that circulated in specialized Cuban journals of psychology and psychiatry during the 1960s. This therapy, which had been developed in Prague by K. Freund, consisted in creating conditioned reflexes. In Cuba it was Dr. Edmundo Gutiérrez Agramonte who incorporated this practice.

Felipe Guerra Matos, the official in charge of the dismantling UMAP, remarked to me during an interview in June 2015, that the idea of placing teams of psychologists in the UMAPs had been his, and that up to 30,000 subjects were confined in them, including approximately 850 homosexuals. At one point in the conversation, Guerra Matos stated, “We committed grave errors, imposing punishments on the little faggots, a lot of things were done there […] They were made to stare into the sun, to count ants […] ‘Go ahead, stare into the sun, you’ll see.’ Any abomination that occurred to some harebrained guard. I am at fault, because I signed off on recruitments.”

The punishments in the UMAPs could range from verbal insults to physical mistreatment and torture. Several of my interviewees assured me that one of the methods of punishment employed by some guards consisted in burying the detainee in a hole in the ground and leaving him with his head exposed for several hours. Some were dunked in a tank of water until they lost consciousness; others were tied to a stake or a fence and left for the night, exposed to the elements, so that they would be food for mosquitos. According to Héctor Santiago, this method of punishment was called “the stake.” The torment and mortification of the body had a purpose of intimidation and formed part of a narrative in which the punishments were given names such as the “trapeze,” the “brick,” the “rope,” the “hole,” among others.

On the other hand, many of the camps were surrounded by barbed-wire fences, used repeatedly in jails and concentration camps. According to the singer-songwriter Pablo Milanés, who was sent to UMAP in 1966, these fences were composed of 14 wire strands, arranged so that they reached up to six meters in height. A brief song is dedicated to this wire fence and the enclosure, entitled, “Fourteen Strands and One Day.” Milanés explained to me that the song was not recorded in those years, but rather later, in the studios of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry, in the 1970s.

Fourteen strands and one day separate me from my beloved,

Fourteen strands and one day separate me from my mother,

And now I know whom I will love

When the strands and the day

I am able to leave.

Epilogue

The history of this sad experiment has remained buried on the Island. Up to today, the Cuban government has constantly denied the character of the UMAPs, and has sought to erase from the collective imagination anything related to this subject. At the same time, the international Left has preferred to view UMAP as an error inherent to revolutionary movements. This ideological exercise has been influenced by the manner in which the figure of Fidel Castro became one of the most powerful representations of the Revolution. Therefore, once the critiques and international campaigns calling for the dismantling of the camps began, it became indispensable to disassociate the Maximum Leader from these processes, so that UMAP could be justified as an exception that should not be identified with the Revolution. This is how, for example, Ernesto Cardenal did it. In his book, En Cuba (1972), the Nicaraguan poet and theologian told of how he was visited by two young men who were interested in complementing his official view of the Island. One of them had been a “jailer” for UMAP, and assured Cardenal that it was Fidel Castro who eliminated those “concentration camps,” invoking at times the law of an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. The picturesque account that Cardenal narrates in his book constitutes the only source that makes this type of reference. In 2010, during an interview granted to the Mexican newspaper La Jornada, Fidel Castro himself finally “assumed” his responsibility in the establishment of those work camps.

UMAP was officially dissolved via Law 058 of October 1968. Although these camps disappeared as an institution, other, more sophisticated devices and institutions replaced them, keeping intact the spirit and motivations that created them. The decade of the 1970s was still to come.

Translated by Alicia Barraqué Ellison