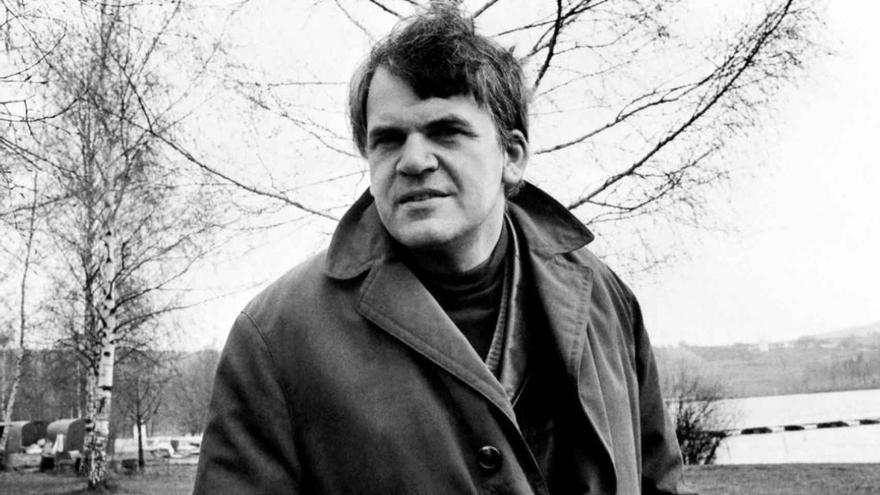

![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 16 June 2023 – Books. I have just read that, over the last few years, Milan Kundera has lost his memory. It’s dramatic that the only real tool that the novelist can count on is so volatile, it overflows and wears out, the years take it from us. I read Kundera for the first time aged 18 or 19. I remember the book itself perfectly – and it makes me sad to think that one day I will forget it – ripped apart, withered, a book whose pages I let fall out at one time by accident.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 16 June 2023 – Books. I have just read that, over the last few years, Milan Kundera has lost his memory. It’s dramatic that the only real tool that the novelist can count on is so volatile, it overflows and wears out, the years take it from us. I read Kundera for the first time aged 18 or 19. I remember the book itself perfectly – and it makes me sad to think that one day I will forget it – ripped apart, withered, a book whose pages I let fall out at one time by accident.

It was, of course, the story of the confused love between Tomás and Teresa, Franz and Sabina, and the mysterious crossings over of those lives – it was not their remoteness that made me feel less familiar with them.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being – very easy to read but very difficult to understand, according to its author – it was the first novel I bought after leaving my country. I wrapped it in newspaper, disguised the cover, so that when I returned no one would take from me this book that was finally mine. When I finally left my house, my city and my things for the last time, it remained behind. I’m not thinking of going back to get it. Ten years have passed since I last opened that book – as a youth, of whom only a ghost remains – when I came across a sentence: “The eternal return is the heaviest burden”.

Escape. After all the love affairs, the books swapped and lost, the conversations in which nothing much is said, the university evenings, the coffee and the pedantic clouds of smoke, what is left to the reader, of Kundera? It’s the feeling that the books have made an older person of them, they have offered them the memory of a man who aspired to have no biography and whose life itself was, in the end, the story of a century.

To read him in a communist country, where his books enjoyed the ’privilege’ of censorship, was to count upon having a manual for survival in this ochre, gelatinous world that produced communism. And nevertheless, the great lesson that I learnt from Kundera was to escape. To run away from all the leaflets and compromised literature, the parties and ideologies, to reject those who expect a simplistic narrative in black and white or in black and red, a pro or anti-government novel, a story through which the publishers can exploit you as exotic, combative, militant, a martyr of freedom. And even further: not to enter into anyone’s club where they have conveniently already received an audience and applause, on one side or another, or found people to whom they could sell the petty drama of the exile or of the conformist.

Dissident. I imagine that Kundera hated the word dissident more than any other. The perverse implications of this term – separate, unorthodox, Cain-like – sound like the uttered revenge of someone who remained, an insult from the ’right-minded’. No one wants to be defined as kind of tumour or a leper that was obliged to leave the country. No one wants their books to be marked out for their bitterness or neglect. Dissident no: I’m a novelist, said Kundera too many times. Opposition to communism isn’t dissidence, but individualism and autonomy. The price is solitude. Nothing more tempting.

Complexity. When a writer abandons the shell imposed on him by his environment – the regime, history, the goodbyes, other writers – only the fabric of memory remains. In this dark room, in the coldness of Paris or some other city, out walking with a woman or smoking alone in a cafe, the words come back to you again. “I want my literature to be united with life and for this reason I defend it from every possible attack”. That is the only true liberty, the only true homeland that a novelist can aspire to. All the rest are fictions that are much less useful than any you could invent, and that no one would read.

Music. To open oneself up to the infinite possibilities of a novel and live for months or years inside the world you’re creating – it can’t be compared with any other job. I find an example in the interview that Joaquín Soler Serrano conducted with Kundera in 1980. He remembers his musician father – the writer himself made a living by playing the piano in restaurants – and offers this lesson: have respect for ’form’ that can only be learnt from music: the changes of rhythm, counterpoint and motifs, the subtlety of composing a book to arrive at the echo, the only echo that remains when memory is gone.

Laughter and forgetting. “Optimism is the opium of the people” writes the protagonist of The Joke, in a postcard to his communist girlfriend. At one time I met a young Czech girl and asked her to pronounce the original title, Žert. It sounded – I wouldn’t know how to pronounce it today – like a gob of spit, a rebellious guffaw, which encapsulated not only that novel itself but also the whole of Kundera’s work and his attitude to austere authority. I demanded she repeat the sound over and over many times. She didn’t get, what for me was the revelation of that word, so elastic and remote, perhaps because to understand one’s own language one also needs to abandon it. I don’t know what happened to the girl, who went back to Prague shorty after.

Finale. You learn how to live and how to write from Kundera. You learn an ethic and a certain kind of healthy cynicism, a mistrust of power and its messengers – success, money, party membership card – and the vertigo of entering into one’s own solitude. The fact that, at 91 he has donated his books and papers to the city of Brno, his native town, was also a harmonic gesture. Or at least a way of saving his memory – the heaviest burden – before death came looking for him.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.