Somos+, José Presol, 7 October 2016 — On October 9 it will be forth-nine years since a man with dirty, matted hair, a lice-ridden beard, boots that were no more than shards of leather and a uniform in tatters emerged from the forest to demonstrate, as he had at other times when he was powerless, his cowardice.

In his delirium he believed he was the most important of world’s exploited peoples, a military genius without equal. He had ventured off to “liberate” new lands but in the end had been put in his place. Trembling, surrounded by dust and enemies, he was a vision of human misery. Desperate, he cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted:

“Don’t shoot! I am Che Guevara. I am worth more alive than dead!”

He surmised they preferred him alive and defeated rather than martyred. Others thought differently. But let’s step back in time a little.

He possessed several “qualities”: an obsession for writing diaries, like those of his motorcycle trip to Bolivia; a lifelong penchant for lying; a devotion to death, his own and others; an inability to finish any project; and cowardice.

Perhaps it was genetic. They say his mother was a progressive. A supporter of the Spanish Republic, she was anticlerical and feminist — though she came from a family of cattle barons whose ancestors arrived in the eighteenth century — and had once wanted to become a nun. After claiming her inheritance, she moved in with Ernesto Guevara Lynch. He welcomed her with open arms, presumably out of love but also because of her inheritance.

His father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch, was also an “aristocrat.” His great grandfather Patricio was the richest man in South America. Like his son and namesake, he went to university but did not complete his studies, though he called himself an engineer. While at university, he distinguished himself by attacking another student, which led to his expulsion. The victim was none other than the writer Jorge Luis Borges, who brought more glory to Argentina than all the Guevaras combined.

After going bankrupt, he used his inheritance to buy a mate farm, whose workers were little more than slaves. He went bankrupt again, and then yet again in a real estate deal. He held his son responsible for the child’s own asthma. And to top it all off, in 1915 he shot the world’s most famous tango singer, Carlos Gardel, then blamed it on his brother Roberto. He spent his final days in the company of his second wife, traveling between Cuba and Argentina, living off his Cuban acquaintances.

Our Ernesto “forgot” things. Even his birth certificate was a lie. It was altered to indicate he had been born prematurely in order avoid the shame of having been conceived out of wedlock.

He started off in medicine but there is no evidence he completed his studies. The University of Buenos Aires says it has no records of him fulfilling the requirements necessary to receive a degree.**

He travelled to America on his motorcycle in hopes finding a job but was arrested in Miami and deported. It seems he had forgotten about being a doctor even before his time as a guerrilla fighter in the Sierras. After he was captured in Bolivia, he wanted to treat a wounded man. When asked if he was a doctor, he said no.

He toured Latin America and ended up in Guatemala, in the middle of a coup d’état against President Jacobo Arbenz. Under the influence of his wife, Hilda Gadea, he began thinking about becoming a Marxist. His revolutionary biographies claim he organized resistance groups but there is no evidence to support this. What is evident is the unreality of his life at this time. In a letter to his Aunt Beatriz, he wrote, “I am entertaining myself here with shootings, bombings, speeches and other activities to relieve the monotony of everyday life.”

When Hilda was arrested, his cowardice resurfaced. He left her behind in prison and fled with his infant daughter to Mexico. Hilda later reunited with him and introduced him to Edelberto Torres, director of a publishing house: Editorial de Educación Pública. It was there that he met Ñico López, who introduced him to Fidel Castro.

The Communists were looking for leaders who could give anti-imperialist speeches while claiming not to be Marxists. Fidel Castro turned out to be one of them. Fidel always liked to have a cohort by his side. At the time, it was a Spaniard, Alberto Bayo. But Bayo could not accompany him to Cuba, so he settled on Che. His simple rationale for this decision was “He’s a doctor.”

We know all too well about his time in Cuba, starting with the execution of Eutemio Guerra in La Cabaña. And the deaths and illnesses of his comrades throughout the world. We are familiar with his initiatives when he was in charge of the Cuban economy; we need only look around. We also know about his lies about the “New Man.” And his cowardice. Once he realized he had become a nuisance, he preferred to leave, without bothering to pay his respects.

His departure marked the beginning of his travels, taking him to Spain and Czechoslovakia. He ultimately found what he was looking for in the Congo. But he ended up fleeing there too, crossing Lake Tanganyika.

In a new diary he laid the blame for his defeat on those “blacks” who did not understand his French, though clearly those “blacks” can communicate perfectly well in French with the rest of the world. Elsewhere he complained about the laziness and uselessness of blacks, Indians and homosexuals.

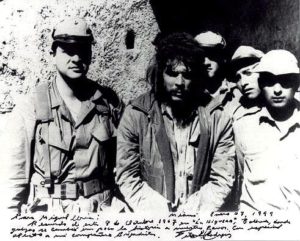

Upon his capture, he was taken to a small school to be interrogated. There he met a “Bolivian” captain named Ramos.

Guevara realized that something did not add up. He said to the captain, “Your accent sounds familiar but it is not Bolivian. Your questions aren’t military questions; they’re military intelligence questions. Who are you?”

Ramos told him his real name: Felix Rodríguez. He said he was Cuban and that he was part of the advance group that infiltrated the island to provide logistical support during the Bay of Pigs invasion. He later described how Che then lost what little composure he had, soiled himself and turned whiter than a sheet of paper.

A coded message was transmitted to La Paz, “Papa is tired,” indicating that Che had been captured and was wounded. The reply was “500-600,” which meant “positive identification” and “execution.” A little later headquarters received confirmation: “Regards to Papa.”

The rest is history, though not the way Fidel tells it. (Yet another lie in the life of Ernest Guevara.) We know all about it. What to do next? Turn him into a martyr and put his image on T-shirts to be worn by all the fools and bourgeoisie of the world.

Translator’s notes:

*Elementary school students in Cuba, at morning assemblies, raise their arms in unison and chant, “Pioneers for communism, we will be like Che.”

**In a blog post, Enrique Ros — author of the Spanish language book, Guevara; Myth and Reality — questions whether Che Guevara ever received a medical degree. He points out that Che could not have fulfilled the stringent academic requirements or the University of Buenos Aires School of Medicine because, during what should have been his final period of study, he was out of the country, “never to return.” When Ros asked the university for a copy of Che’s transcripts, he was told they could not be provided because they had been stolen.