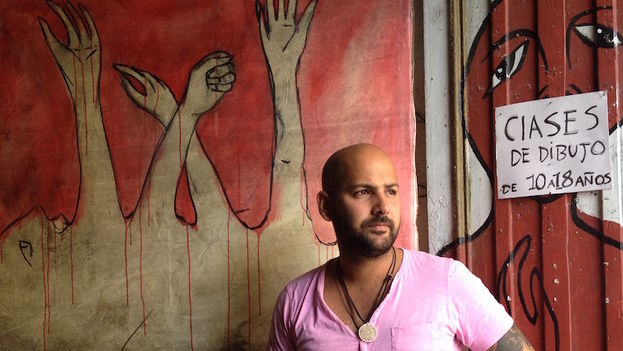

![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 3 March 2016 — They never accepted him at the San Alejandro Academy. Perhaps this is why, the work of the artist Yulier Rodríguez Pérez (1989) is not part of the narrow mold of what is learned in the classroom. He came from Florida, Camagüey, to settle in Havana in an aunt’s house with the obsession with being a painter. Along the way, he realized that he did not need a gallery, but to go out in the street and take this space to leave his work.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 3 March 2016 — They never accepted him at the San Alejandro Academy. Perhaps this is why, the work of the artist Yulier Rodríguez Pérez (1989) is not part of the narrow mold of what is learned in the classroom. He came from Florida, Camagüey, to settle in Havana in an aunt’s house with the obsession with being a painter. Along the way, he realized that he did not need a gallery, but to go out in the street and take this space to leave his work.

Luz Escobar. You are known as a painter, graffiti artist and sculptor; which of these artistic aspects do you most identify with?

Yulier Rodriguez Perez. I associate more with street art and don’t try to correct that version, because of the visibility my work on the street has given me. But it all starts in the studio, the workshop and the canvas. All these characters that form our reality through my perspective of the everyday come out on the easel. I live in the Industria y Trocadero district, so I live in shit and work on Prado Street, which is more shit. All the daily cinematography of these slums guides me in finding my own discourse.

Escobar. What are the motivations that most often lead you to the easel, the wall or the drawing paper?

Rodriguez. My pictures are like fables, a portrait of people’s experiences. Others are more personal, but almost always reflect neglected and discontent scenes. They are like souls, because at some point we stop being people and now we are souls in a purgatory called Cuba.

We live condemned by ourselves, because this is the result of our decisions and our inability to see beyond the fear and a thousand other things. The images are just that: our souls that reflect the internal pain, the impotence, the fear and the sadness.

Escobar. Choosing as an exhibition gallery facades and bus stops is not very common among Cuban artists. What made put your hand to this singular exhibition hall?

Rodriguez. I presented several projects in galleries and exhibitions, but I was always marginalized. In the best case they told me I would have to wait a few months. I offered a work now and it would be shown in a year, when at best I was no longer thinking about it. The work evolved and my intention as an artist had never been to have a retrospective of my art, but to share it with the public at the moment it was created.

A friend in the urban art scene in Germany came to Cuba and we started to do things. One day we went out to paint at night, everything was dark and I didn’t know anything about this world. It caught me, it was like an adrenaline rush and I was there with another graffiti artist who wasn’t very well trained artistically, his work was more about making letters, but he had experience as a street painter, he had lost his stage fright. That union helped me a lot and I started to do my work.

Escobar. During your years as a street artist did you ever fear reprisals for your work?

Rodriguez. At first I was worried because the pieces showed a reality that many people do not want to see and others don’t want to be seen. At the end I was losing my stage fright on the fly and I started helping my friend with the theoretical part of conceptual expression, finding a language. It was a mutual help. Then he left the country.

Escobar. What are the antecedents of graffiti art in Cuba?

Rodriguez. The lack of examples of street art is very strong. Who can I mention? Street Art, with Maldito Menendez, but the majority of them don’t live on the island. There is no urban Cuban art, right now there is no movement, there are isolated artists working and that’s good. I only know two who speak of the reality, El Sexto and me.

The difference between El Sexto and me and that he takes an essentially political posture and has declared war against Fidel Castro. That is his posture and I respect it. He does totally political work, he is an activist, while I dialog with the public through art and a more elaborate style with a certain lyricism. My work isn’t linked to anyone, I defend my opinion, I like art and I self-finance everything I need to do this work.

If right now El Sexto and I quit it’s hard to find others who, in a serious and constant way, see this as an artistic expression. Once we tried a collective painting in El Cerro, but people from the government appeared with their story of counterrevolution and cut off everything.

Escobar. It’s hard to believe you’ve done all these paintings on the walls of Havana and you didn’t have any problems with the police. Have you been arrested or fined?

Rodriguez. I’ve never had problems, but once in a while they send out the police. Working in the street is very sensitive, but I believe it had to open up. The Cuban cinema, for example, is showing the reality in a more raw way and they have had to let them because it can’t go against reality. When I came out with these visual chronicles it was the best, because I had already had a small opening, bit by bit. Now things can no longer be hidden like before.

Escobar. Have you ever slept in a cell because of your art?

Rodriguez. For me that is a mystery, because they have sent out three police patrols and nothing happens. They came predisposed and, when they got out of the car, and looked at the piece and listened to my explanation, they called on the radio and said, “the boy isn’t doing cartoons, it has nothing to do with politics.”

So far they have let me go. The only time there was friction with the police was at the Villa Panamerica [sports complex]. At the stop I did a graffiti of people standing on the wall in various awkward situations, like shouting. That day the order came from above. A woman from the (Communist) Party had passed by on a “camel” [a kind of urban bus] and called the police to tell them that I was doing “something counterrevolutionary.” At the police station they sorted it all out, it wasn’t even 20 minutes, the same guard told me to get a permit. I explained that was exactly why I had gone to the streets, because the permissions are very slow and if you waited for them you would never paint.

Escobar. What are the most frequent places where you have painted?

Rodriguez. I do not invade any place, rather I look for destroyed walls and places. I try to give them some aesthetic value and thus promote a future urban art movement.

Escobar. It is common for graffiti to get covered with dabs of paint or pro-government slogans. Has this happened in the case of your work?

Rodriguez. Most of my graffiti has survived, some of mine has been painted over by the government, but others have been painted over by others. I have a stronger enemy than the government, which is religion. It has already happened several times that Jehovah’s Witnesses or Christian extremists see in my work diabolical figures and they erase them.

Escobar. So far, have you only been displayed in the streets or in a workshop, or have you also managed to hang some artwork in a gallery?

Rodriguez. I participated in some group exhibitions, including one here at the Central Park Hotel, and a personal one in Light and Crafts. This year I want to organize a show with the rubble of collapsed buildings, bringing them to the workshop and painting them. I see the rubble as a historical document that holds the memory of those buildings where people lived and suffered in a space of time and they are pieces of our identity.

Escobar. The José Martí Community Workshop, where you do part of your work belongs to the Prado People’s Council. How does it work?

Rodriguez. I’m in charge of this project that interacts a lot with the community. We do drawing workshops for children and our doors are always open for any activity. What I do is I will not allow this to become trinkets for tourists. We try to maintain works that take off from sincerity and seriousness. Many people left because they were not prepared to work on those terms, three or four of us remain. We have been improving the space with a great deal of our own effort, because it was in very poor condition.

Escobar. What artists have most influenced the way you carry out your work?

Rodriguez. I agree with Banksy in the way of seeing street art. For me, street art is a dialogue with the public and my work is that.

Escobar. Is there any work that you remember with particular enthusiasm?

Rodriguez. During the Book Fair, I did a public intervention that is on my Facebook, where I crossed swimming from one side of the bay to the other to paint a huge face with no mouth, no ears, no nose, only eyes. I did it so it can be seen from the far side. Then I swam back to the Malecon.