I do not think there is a single Cuban who has not seen his face at some point, on the big screen or small, or in a theater. He is one of the most recognizable actors on the national scene.

No doubt this is influenced by the not inconsiderable number of his films: 80 works, including feature and short films, foreign films and Cuban-foreign co-productions. An astronomical figure for an artist of this always limited island.

From movies such as Clandestine, or Lovely Lies; through Guantanamera directed by the most brilliant Cuban filmmaker in history, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea; and ending recently with The Skinny Prize by Juan Carlos Cremata, Luis Alberto Garcia is key to an effort to assess the cultural output of the Cuban nation.

Among other reasons, because he is an actor with a strong intellectual stature — shared by few — who has earned the respect of the public and his colleagues, and because he has involved himself in projects which, for another person, would be an unthinkable recklessness.

Nicanor O’Donnell’s character in the series of short films directed by Eduardo del Llano, has affected Cuban society enormously, as an avidly-consumed underground product. The shorts, despite their illegal circulation, have had repercussions in all areas, including of course the Internet.

Thus, for the inveterate eavesdropper that I am, a contact with “the true Nicanor,” a funny man who plays the character, was almost mandatory.

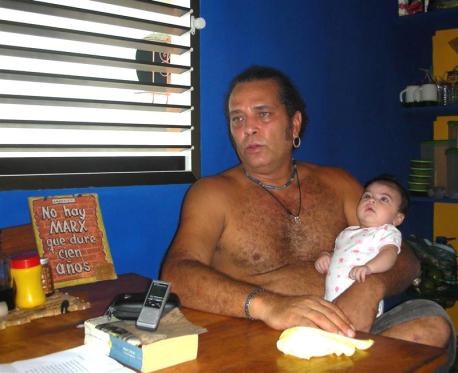

Below is a brief excerpt of the dialogue we had in his apartment in Havana, just four days ago, while Luis Alberto fed, tried to put to sleep, and washed, his little baby of two months old (who is named, by the way, Vida (Life).

The need to be a most loving father did not stop him from giving me a great interview, full of ironies, smart thinking and a lot of honesty, which I assume will be a special text in my journalist’s book.

Luis Alberto, in an interview with Edmundo Garcia for Night Moves, you said you would not be recognized in the Cuban series, nor on national television. Who wouldn’t recognize you in the country where you live. And what do you think you of this fact?

Look, the error has always been in the philosophy of a kind of “besieged fortress” that they have wanted to instill in us over the 50 years they’ve been in charge.

There is very strong thinking, extended in all areas, that says that airing the dirty laundry, and hanging it out in the sun, undermines the process. They’ve always seen it this way. From his “Words to the Intellectuals,” Fidel’s discourse hangs on this question.

Starting in 1961 when Fidel said “Inside the Revolution everything, against the Revolution, nothing,” it has sparked thousands of questions: Who decides what art work is against the Revolution or which is in support of it? Who decides which product is beneficial to a social process, and which is not?

It has always seemed a little absurd to me, then life showed how damaging this thinking has been. It’s all very well to say it in a speech, it’s even a great phrase, if you will, but to put it into practice is a problem, because then, when a boy in Ciego de Avila writes a play, should we take it to Fidel and say, “Comandante, read this work so that you can decide if it is within or outside the Revolution”? That is nonsense.

And as this is impossible, it then creates another major problem: after Fidel’s words, come the “interpretations of the words of Fidel,” and each person who has occupied a key position in the culture of this country, has thought differently in that respect, depending on their prejudices and cultural level.

So then, what is easiest? Instead of dealing with it work by work, author by author, they said, “We’re not going to put any of the defects of the country, or the mistakes of the Revolution, or the problems of our society, in any work of art, because that is giving weapons our enemies. And since we are a blockaded country, giving weapons to our enemies means that a work that shows the bad, the ugly, in this country, is a book that automatically sides with the enemy.”

That is complete rubbish, to ask the art that not reflect its surroundings. The artist has no choice but to talk about what he sees around him, of how bad or how good is their reality. Do not ask the impossible.

So then, I said to Edmund, what happens to me as an actor is that the reflection of the reality I live is so far from what I see in the series or on TV programs that I don’t recognize myself, I find nothing in common with myself.

So then, I said to Edmund, what happens to me as an actor is that the reflection of the reality I live is so far from what I see in the series or on TV programs that I don’t recognize myself, I find nothing in common with myself.

What is the sense, then, that every day in this country they tell us, when we’re children, that we shouldn’t lie, we have to tell the truth, and then when we become adults they say to us, “Yes, the truth but not the whole truth.” Or that terrible phrase, “Not all truths are for all ears.”

It is a culture of obscurantism, of having to hide the ball from people, which is intolerable.

I, for one, am still wondering what happened those who died at the “Mazorra” Psychiatric Hospital last year. The newspaper in my country said it would open an investigation to determine the causes and punish the guilty… where is that investigation?

I’m still wondering what happened to the police who beat the Industriales team in the Sancti Spiritus stadium, which was recorded by several cell phones and traveled across all the computers in this country.

Someone told me the other day: “They were prosecuted.” Fine, but I have every right in the world, as a citizen of this country, to be told that they were sanctioned, and how, so that will not happen again.

Because the images of that beating in the Sancti Spiritus stadium are not different in any way from those I saw when I was making Clandestine: Batista’s police clubbing the boys of the “26th of July Movement” in the Cerro stadium. There were the same billy clubs, the same slaps in the face, dragging people along the ground. And I need, or better yet as a citizen I demand, that someone give me an explanation.

Another, more all-encompassing example: the decision to show the video that proved the alleged errors of this country’s high officials, Felipe Pérez Roque and Carlos Lage, was made in high places, I guess. But that decision was to show the video only to Communist Party members.

My question is very simple, were they really traitors, or were they traitors only to the members of the Party? Or was it to a whole people who trusted in their efforts to improve the lives of ordinary people?

So, is it that not all truths are for all ears, and that not all the realities can be shown in this country? That’s a terrible thing. It’s like living in a house where you’ve been taught to think with your own head, but when you grow up you discover that there are rooms in this house you aren’t allowed to enter, that they’re shut, lock stock and barrel. Inevitably, if you’re an intelligent person, and if you really thirst for knowledge, sooner or later you’re going to open those doors. With or without permission.

What is needed is the political will and honesty to change our ills, to address them without hypocrisy. It requires political will to say, “Gentlemen, hiding this shit has nothing to do with us. You have to throw the shit against the fan. The dirty laundry needs to be washed, and put out in the sun. Because you decide to hide it in this basket today, and in another one tomorrow, but the clock is ticking and one day we’re going to be overwhelmed with the baskets of dirty clothes.

This is very much related, Luis Alberto, with the answer you gave another journalist in Gibara, when he asked you to summarize in one sentence what you mean in the short film Brainstorm. You told him, “Cubans deserve a better press.”

Of course.

And what that means is simply: I don’t want to learn from foreign stations, from foreign news agencies, from a television program in another country, about what happens where I live. Because even though we Cubans don’t have internet or cable television, these materials always come to us, and we learn days later about things that went on around us.

And what that means is simply: I don’t want to learn from foreign stations, from foreign news agencies, from a television program in another country, about what happens where I live. Because even though we Cubans don’t have internet or cable television, these materials always come to us, and we learn days later about things that went on around us.

I don’t want the news media of this country to keep publishing things six days after they happen, because whatever it is has become a big deal internationally so then they have to explain to people somehow what happened.

I want the press to tell me about the country where I live. To keep me informed. But not to hide mistakes from me, nor give me adulterated figures.

Look mister, if Zapata was on a hunger strike and died, it’s not pleasant to have to break the news to people. Certainly not. Life is full of disagreeable things. But people here, inside, have the right to know what happened, and no one should steal that right from them.

Many time, for example, we see on the news, “A response to something a woman blogger said on some site,” and you go out in the street and a lot of times people don’t know who this person is. Then they don’t understand the official response, nor can they measure or evaluate for themselves what the blogger said.

And it’s sad that Yoani Sanchez is known by the entire world, and someone who lives across the street from here doesn’t know who she is. It’s humiliating for Cubans, nothing more nothing less.

Please… We have to take the bull by the horns. This will oxygenate the lungs of this society. This transparency, this truth, will be vital to start building a better country.

For me, at least, I need transparency and truth. And when I feel like they are hiding the ball from me, it irritates me and then I go looking for the truth the press of my country doesn’t want to offer me.

I’m sure that this happens to everyone who flatly refuses to behave like sheep. No offense to anyone.

November 8, 2010