By Ernesto Santana

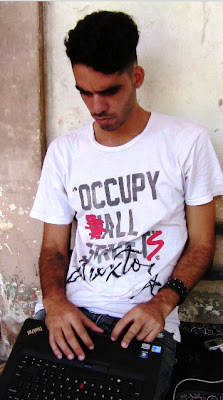

In his five years as a graffiti artist Danilo Maldonado, El Sexto (The Sixth), has gone through violent and arbitrary arrests, the seizure of his personal property, threats and other abuses, but has continued to stamp his works throughout Havana.

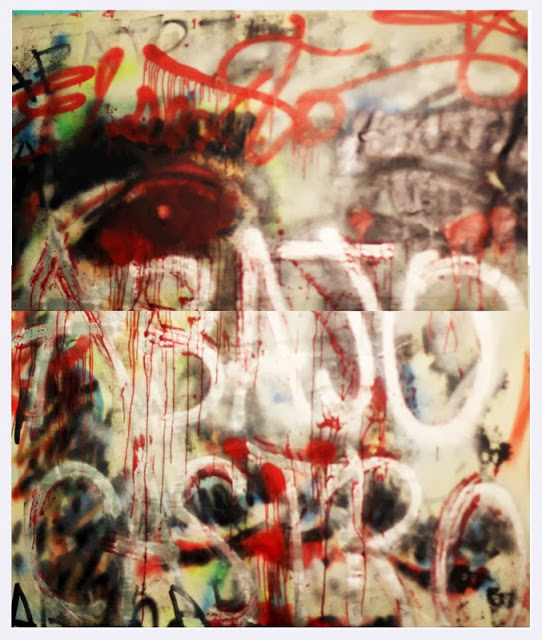

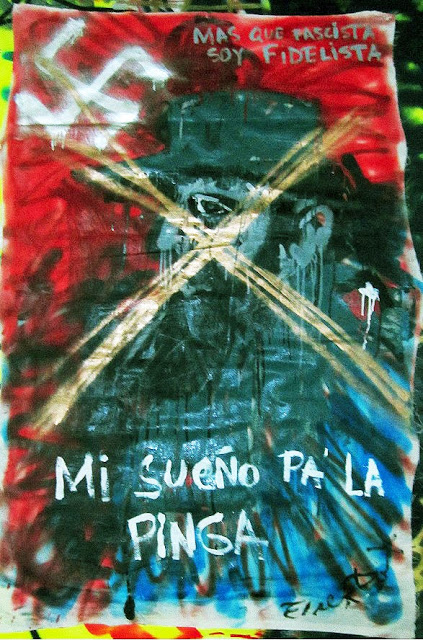

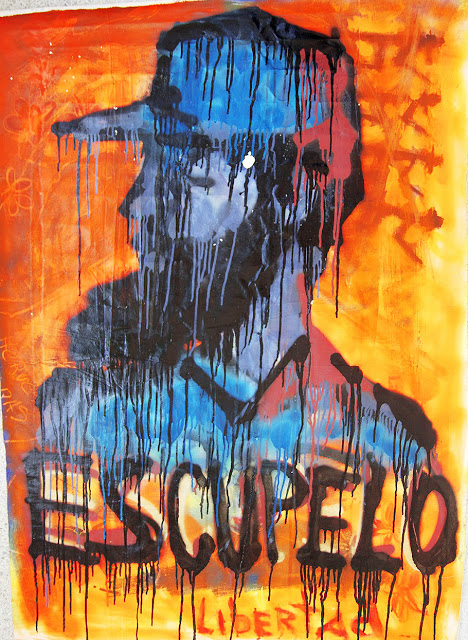

State Security has kidnapped him and even taken him to visit Alexis Leyva, Kcho, an “example of artist” according to them. In vain, El Sexto, is backsliding and the direct and confrontational tone of his art grows ever stronger. If at one time he used great ironies such as “Return my five euros,” he now puts “Down With Castro” on a bloody background or paints a swastika over the face of Fidel Castro.

“I’m like a dog with a bone,” says Danilo in conversation with this reporter, “even though every time they erase my graffiti faster.” When they increased the pressure on him, he decided to combine the marginal arts of tattoo and graffiti and began to draw on his own skin what he wanted to denounce; and in addition, as an example of his persistence, he wrote his signature over the police pink paint-outs over his previous graffiti.

But they have to catch him in the act to stop him. Simply carrying a spray can in his pocket, as happened on Friday May 17, when he went with some friends to buy some beer at the corner of Twenty and G about nine in the evening. A policeman asked for documentation and took him to the station at Zapata and C, where he had to wait until the next day to meet with the chief of the station.

“When I finally talked to him,” Danilo said, “he asked me, ‘So you’re the one who does all that out there?’ I gave him a disc with my work, so he would know what I was doing. ” The reaction was take odor samples (they tried to get him to give them urine samples, but he declined, although they disrespected him with extreme rudeness) and they took him in two patrol cars to make a search of his home.

“They started to take canvases, sprays, a laptop, a camera, memory cards, discs and unused canvases, and put everything in nylon bags that said ‘Forensics’,” El Sexto said. Then they took him back to the police station and at midnight that same Saturday, the 18th, they returned to take him to the office of the chief, now absent. “There was a woman who behaved with very little respect. All my belongings were on a table, any old way, all mixed up,” says Danilo.

The officer informed him that three of his paintings would be confiscated, as well as templates for stencils, his artistic projects, thirty-seven enamel spray cans and even four cans of oil paint and even his resume, arguing that they were objects related to “a crime under investigation.” Then they handed him a record of what had been seized and released him.

The officer informed him that three of his paintings would be confiscated, as well as templates for stencils, his artistic projects, thirty-seven enamel spray cans and even four cans of oil paint and even his resume, arguing that they were objects related to “a crime under investigation.” Then they handed him a record of what had been seized and released him.

Not Unemployed: Artist

Two days later, El Sexto started a legal process with an attorney to get them to return what they had seized him, because when they searched his home and confiscated objects, he was not given a copy of what confiscated, as dictated by the procedures. “Why did they return some works and not others?” the graffiti artist asked. “Why did they keep the spray paint that I bought at State stores? They did what they felt like, violating many things,” he said.

He had been branded unemployed and he had replied: “I am an artist, although I am not your artist. I’m not here to worship any god. I have the right to criticize and say what I want.” And it was more clear when he told the police: “You’re not talking about some revolution, but a phalanx who loves the F of Fidel. It is illegal for me to paint the walls, but not to write “Long live Fidel” or “In line with Fidel” without asking anyone. Why do I have to check with you to say something?”

Determined not to be passed over, he will continue to demand the return of his works. “I did not kill anyone, I am an honest person, I live in my work and my wife is pregnant,” he pointed out to the officer. “In fact, my greatest endorsement is what you do, punishing me, which confirms that I’m doing my job. How ironic.”

When the informed his attorney that a file had been opened on his client, the counsel asked what he was accused of, and the only response, according to what Danilo said, “they told him they couldn’t tell him, because it was a secret process. I insisted, but the only thing they told me was “soon” they would tell me what I was accused of. They alleged that it was a falsehood that they’d made an accusation and that I had refused to sign it. But we wrote letters of complaint and delivered them to the appropriate places,” Danilo Maldonado concluded.

The Criminal Value of the Artwork

The Criminal Value of the Artwork

From these events, Otari Oliva, one of the project coordinators of Christ the Saviour Gallery (which did a great series of exhibitions of Cuban graffiti between September and November), wrote a text setting out his concerns as an artist: “The situation of El Sexto makes me reflect: a work of art can possess criminal value and this is referred to in the criminal code of my country. Starting today I would like to be able to determine, as I can determine the criminal value of certain acts, the criminal value which may lie in a work of art.” And then he made his position clear: “Either the criminal code will be adequate and judgment will be pronounced from an exercise in transparency, clarifying for Danilo and everyone the reasoning of the authorities, or we are dangerously close to a burning pyre of books, in addition to the hands of our artists trembling perhaps a little more from now on.”

Either way, El Sexto does not have among his plans, backing down. In the coarse search they did of his home, the experts like a bag with the word “Forensics” printed on it, which he now thinks of using to create a work. A gift that they gave him to continue honing his art.

Photos courtesy of Ernesto Santana. Originally published on Cubanet.

30 May 2013