An anecdote not often shared relates that, at the end of a meeting between Fidel Castro and Cuban artists in 1969, where he pronounced his polysemic “Words to the Intellectuals,” a discordant — and unexpected — voice spoke up.

It was Virgilio Piñera, perhaps the most immortal and lacerated playwright our Island has given birth to. A frail man who, facing the Commander in olive-green with his six feet and more and his gun in his belt, must have seemed like an insignificant blade of grass.

They say that, once in front of the microphone, pale due to his natural color and because of his nerves, the interjection of the effeminate Virgilio took less than ten seconds.

“The only thing I can say is that I feel very frightened,” he said. “Only that. I don’t know why, but I am afraid…”

His tortured life didn’t allow him to know that he wasn’t wrong that time, that fear would be his destiny.

I think of Virgilio when I hear from the mouth of another intellectual, and friend, very similar words. The only difference is that this teacher, this young writer knows perfectly well why he is afraid.

His name is Francis Sánchez and, like me, he lives in a little provincial city, Ciego de Ávila, where exercising individuality implies more risk than in the cosmopolitan capital. For a long time his name has been known among professionals of letters for his literary laurels, and his publications in the country’s diverse magazines.

Anyone who sees him, with his nicely fleshed-out body and his well-trimmed mustache, would think he was the most complacent and docile of citizens. A perfect pater familias who, like any ordinary Cuban, deals with the shortages and dissatisfaction. And shuts up.

But Francis Sánchez bears a cross of ashes on his forehead: he has never consigned himself to renouncing his condition as a free man, his condition as a non-conformist Cuban who doesn’t know how to close his eyes against the reality he doesn’t like, that doesn’t suit him.

Like a good man of letters, knowing the absolute impossibility of publishing his questioning articles in any institutional media, the personal chronicles about the country that he longs to have and doesn’t, he decided, like many of us, to open his personal blog. If I remember rightly, he just opened it with the excellent name: Man in the Clouds.

But Francis Sánchez is afraid, and doesn’t hide it. He tells me:

“You are a single boy, Ernesto. We are four. It’s not the same.”

And suddenly I feel very small, devoid of reasons before a circumstance like this: an honest Cuban has decided, knowing the risk, to endanger the stability of three people other than himself: his wife and their two children. And he has decided not how we choose one option ahead of another, or how we shuffle the possibilities on the negotiating table. No. Rather, he is someone who cannot contradict his abiding spirit, and who knows that it may cost him very dearly, and be very hard, but still he crosses the thin line.

One of his phrases has left me trembling like a leaf. He told me, with subtle indignation:

“I feel very afraid, not for myself, but about what could happen in the future to my family. And this fear only irritates me more. Because the fear is the most incontrovertible evidence that I must confront the country in which I live: I don’t want to feel afraid! I shouldn’t be afraid if the only thing I am trying to do is to express what I think!”

His rationale is scathing. Absolutely no one should fear for his integrity, social stability, if what he wants to do is done everywhere in the world of free people: raise his voice against the imperfect, the deformed, what he considers unacceptable. We should fear terrorists, pedophiles, those who corrupt. But men with their own voice, never.

But, that is the daily life of Cubans.

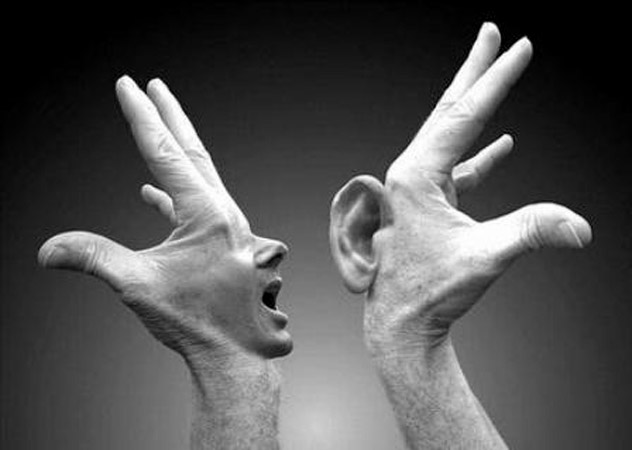

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard, from the mouth of one person or another, “I would love to do what you are doing, but I can’t.” And then, a long or short list of reasons that sweeten a painful reality: fear is stronger than the need for expression.

And so the mask never fails to hide the unpleasant features of our personality, and to camouflage the fear that takes hold in the most varied pretexts.

What are the most frequent arguments I hear in this regard? In the first place, the impossibility of survival without the employment offered by the State. Some say, “If, like you, I had at least one family member outside this country who could help me economically, I’m sure that I would have founded a Party, I would no longer go to the polls, I would say what I think in the assemblies at work, I would have opened a blog.”

Others say, “If I didn’t have a family to support, I would have exploded long ago and would have screamed at the officials everything I think of them.”

There is something undeniable, beyond ethical and moral judgment, that these words prove: There has never been a better partner for totalitarianism than naked fear. If this century’s technology has been the worst enemy of those who would like to control the minds of men, since ancient time it has been fear that has provided the fuel to sustain the machinery of the dictatorships.

What do people really fear in my socialist Cuba? It’s worth asking. It’s not the fear of death or disappearance, as used by tropical dictators like Trujillo or Somoza. The Cuban people’s fear is more ethereal: the fear of disintegration as a social being.

Losing a job without any possibility of finding another livelihood; the constant defamation surrounding a person; the exclusion from spaces and organizations that you used to frequent, and as may be the case, being refused admittance even to public cultural institutions. Add to that suffering constant harassment not only against yourself, but worse still, against your loved ones and your friends. And, depending on the strength of your positions and your consequent activism, physical repression and prison.

So the more I think about cases like that of Francis Sánchez, and so many others who once broke their chains and decided to play according to their own rules, I remember the vibrant words I heard from the mouth of Father José Conrado: “We are all afraid. The essence of the totalitarian system is precisely to provoke a response of paralyzing terror. The problem is when one has to conquer it in the name of a great responsibility.” And there are many more examples, dignified, beautiful, which make me believe more and more that to rely on presumed accommodating arguments is an irresponsibility that is even more costly, in terms of the eternal weight on one’s conscience.

After listening to Pedro Luis Ferrer quote his favorite phrase — “Nobody knows the past that awaits him” — I discovered what is in truth the greatest of my fears, the supreme terror I could not face: the fear of facing, in the future, my children and my grandchildren, and having to explain to them where I was and what I was doing when my country was suffering so much fear.

Now that President Raul Castro has said, with regards to the 6th Communist Party Congress, that from this point forward the only necessity is that each Cuban speaks the truth, whatever that might be, and that everyone must do so without fear (his exact words, confirming an open secret: Cubans have a sense of raging panic around expressing their truest opinions), I think it is the perfect time for all of us to dedicate five minutes to self-examination, and of taking the President-General at his word, lest we soon repent our failure to do so.

December 21, 2010