For the third time in a row a writer from our island is honored with the Premio Novelas de Gaveta “Franz Kafka,” awarded by its Czech sponsors to the Carnival and the Dead, by Ernesto Santana, who introduced it in a brief evening ceremony on Friday, December 13, at the apartment of Yoani Sánchez and Reinaldo Escobar, creators of the Cuban Alternative Blogosphere Academy, a civic non-profit entity that disseminates new technologies and citizen journalism.

For the third time in a row a writer from our island is honored with the Premio Novelas de Gaveta “Franz Kafka,” awarded by its Czech sponsors to the Carnival and the Dead, by Ernesto Santana, who introduced it in a brief evening ceremony on Friday, December 13, at the apartment of Yoani Sánchez and Reinaldo Escobar, creators of the Cuban Alternative Blogosphere Academy, a civic non-profit entity that disseminates new technologies and citizen journalism.

The words of praise were delivered by the writer Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo, winner of the 2009 Kafka prize for his story collection Boring Home. A critical appraisal of Pardo Lazo on the literary works of Ernesto Santana will be published in the next issue of the Voices digital magazine and commented on in this Cubanet blog, Island Anchor on the Voces Cubanas portal.

In 2008 the Premio Novelas de Gaveta “Franz Kafka” was awarded to the Habanero Orlando Freyre Santana, author of Blood and Freedom, which addresses, in fiction, the struggles against the Cuban military dictatorship.

In 2008 the Premio Novelas de Gaveta “Franz Kafka” was awarded to the Habanero Orlando Freyre Santana, author of Blood and Freedom, which addresses, in fiction, the struggles against the Cuban military dictatorship.

The essay competition, sponsored initially by the Independent Library Movement and the Czech Republic NGO People in Need, is an option for authors who live on the island and have no chance of publication, such that their texts are sleeping in drawers and computers. It requires of the participants an unpublished and exclusive text.

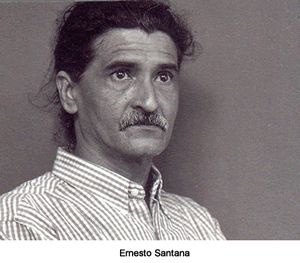

Ernesto Santana (Puerto Padre, 1958) is an agile prose narrator, whose works oscillate between realism and the poetry of memory. In 2002 he received the National “Alejo Carpentier” Award.

As it is not possible to read and review a 174-page novel in a single weekend, I offer the reader a summary of the review written by Carlos A. Aguilera on The Carnival and the Dead, by Ernesto Santana.

As it is not possible to read and review a 174-page novel in a single weekend, I offer the reader a summary of the review written by Carlos A. Aguilera on The Carnival and the Dead, by Ernesto Santana.

“More than desire, disease, or Africa, the new novel by Ernesto Santana is about the dead. The dead that a determined ideology have produced. His characters, shadow plays acting up against a vacuum, are turned into characters almost in contradiction to themselves. They are skinny, alcoholics, hard; sons of quarrelsome mothers and sleepwalkers of war. The come and go from nowhere, as if life (that place where everything is defeated) had taught them to swim precisely so they would drown. And from this suffocation, which in turn is pure pleasure and extreme ordinariness, The Carnival and the Dead draws its story. The rest we could talk about is their different voices, their geographic countries, their veracity. But none of this is as important as knowing that The Carnival and the Dead is a “dance macabre,” a dance where we find nothing more alive than the dead.”

December 9 2010