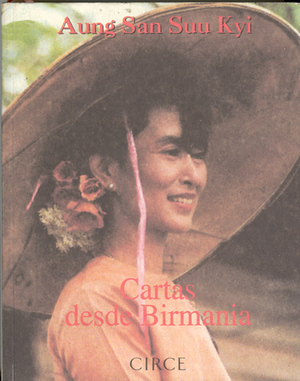

In one of life’s random events I came across Letters From Burma by Aung San Suu Kyi in a Havana bookstore. I didn’t find it in one of the individually managed stalls selling used books, but in a local State store that sells colorful editions in convertible currency. The small volume, with a photo of her on the cover, was mixed in among the self-help manuals and recipe books. I glanced to both sides of the shelves to see if someone had put the book there just for me, but the employees were sleeping in the midday heat, one of them brushing flies off her face without paying me any mind. I bought the valuable collection of texts written by this dissident between 1995 and 1996, still taken by the surprise of finding them in my country where we, like her, live under a military regime and strong censorship of the word.

In one of life’s random events I came across Letters From Burma by Aung San Suu Kyi in a Havana bookstore. I didn’t find it in one of the individually managed stalls selling used books, but in a local State store that sells colorful editions in convertible currency. The small volume, with a photo of her on the cover, was mixed in among the self-help manuals and recipe books. I glanced to both sides of the shelves to see if someone had put the book there just for me, but the employees were sleeping in the midday heat, one of them brushing flies off her face without paying me any mind. I bought the valuable collection of texts written by this dissident between 1995 and 1996, still taken by the surprise of finding them in my country where we, like her, live under a military regime and strong censorship of the word.

The pages with Aung San Suu Kyi’s chronicles — reflections on everyday life mixed with political discourse and questions — have barely touched the shelves of my home. Everyone wants to read her calm descriptions of Burma, marked by fear, but also steeped in a spirituality that makes her current situation more dramatic. In the few months since I found the Letters, the vivid and moving prose of this woman has influenced the way we look at our own national disaster. The thread of hope that she manages to weave into her words instills in them an optimistic prognosis for her nation and for the world. No one has been able to describe the horror from the sweetness as she has, without the cries overwhelming her style and the rancor being reflected in her eyes.

I can’t stop wondering how the texts of this Burmese dissident made it into the bookstores of my country. Perhaps in a bulk purchase someone slipped in the innocent-looking cover, where an oriental woman tucks some flowers, as beautiful as her face, behind her ear. Who knows if they thought it might be from some writer of fiction or poetry, recreating the landscapes of her country motivated by aestheticism or nostalgia. Probably whoever placed it on the shelf didn’t know about her house arrest, or the richly-deserved Nobel Peace Prize she won in 1991. I prefer to imagine that at least someone was aware that her voice had come to us. An anonymous face, some hands quickly placing the book on our shelf, so that when we approached it we could feel and recognize our own pain.