The experience of being treated like criminals for the simple fact of living freely crudely revealed to us the true face of tyranny.

![]() 14ymedio, Rafael Bordeo, Miami, 25 September 2025 — This September 25th marks the 57th anniversary of the incident in which thousands of young people were rounded up from the streets and restaurants while enjoying Havana’s nightlife. We were all arrested without committing any crime. We were taken directly to State Security, booked without charges or explanation, and after three days of uncertainty, we were dispersed among prisons and farms in the province of Pinar del Río.

14ymedio, Rafael Bordeo, Miami, 25 September 2025 — This September 25th marks the 57th anniversary of the incident in which thousands of young people were rounded up from the streets and restaurants while enjoying Havana’s nightlife. We were all arrested without committing any crime. We were taken directly to State Security, booked without charges or explanation, and after three days of uncertainty, we were dispersed among prisons and farms in the province of Pinar del Río.

We were accused—in this ideological hunt disguised as public order—of “improper conduct,” a law that didn’t exist and of which not even the lawyers were aware of. And all of this happened in Havana’s Vedado area: La Rampa, the Capri Hotel, the Coppelia ice cream parlor, the Rivero Funeral Home cafeteria, and in nearby cafes, places that until then had been refuges of freedom and expression.

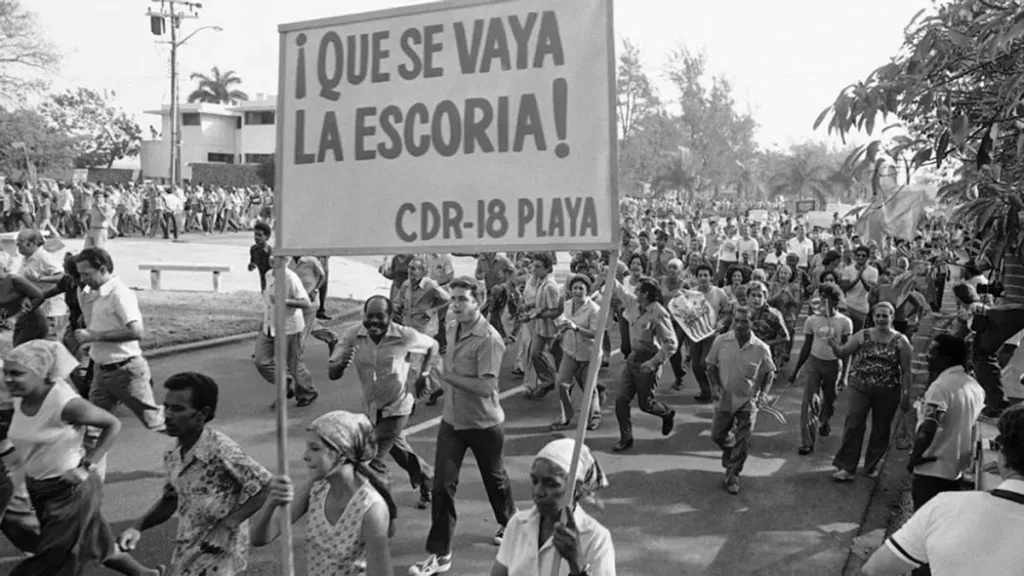

Castro took advantage of the fact that the United States was reeling from the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, that Paris was burning with student strikes, and that Russian tanks—with Havana’s approval—had invaded Czechoslovakia. All these international events, in addition to the Tlatelolco massacre—which shook Mexico on October 2, a week after the raids in Havana—meant that very few outside of Cuba were aware of this human rights violation committed (like so many others) by the Castro dictatorship, which was beginning to radicalize with the USSR.

I was imprisoned for a year and 16 days for standing on the corner of 21st and O (on the Capri sidewalk, across from the Los Andes restaurant) watching the happy passersby strolling along. The reason for this unexpected arrest was our youth: our love of American music, foreign fashion, free love, and our growing hair. We wanted to reclaim what had been taken from us: freedom, chewing gum, Pall-Mall cigars, Dunhills, Chesterfields, Levi’s Strauss blue jeans, Paul Anka and Sonny & Cheer records. And they forbade us (although we never obeyed them) from listening to the music that all the young people of the world were listening to: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, The Doors, The Byrds, The Supremes, The Mamas and the Papas, Stevie Wonder, Simon and Garfunkel, etc. They abolished all Hollywood films to show Russian films full of depressing misery. Then came Japanese, French, and Italian films to ease the pressure on the capital’s rebellious youth.

When the events at the Peruvian Embassy in Havana broke out in 1980, followed by the Mariel boatlift, we didn’t hesitate. We jumped at the possibility of another destination.

That mass arrest on September 25, 1968, failed to tame our attitude; on the contrary, it inflamed it even more strongly. For many of us, the experience of being treated like criminals for the simple fact of living freely—of listening to forbidden music, dressing as we pleased, or thinking without commands—crudely revealed the true face of tyranny. What was intended to be a lesson in obedience became a school of resistance. The humiliation, the confinement, the legal arbitrariness made us understand that there was no place for us in that social experiment, which called us “the new man” while denying us the right to be simply human.

So when the events at the Peruvian Embassy in Havana erupted in 1980, followed by the Mariel boatlift, we didn’t hesitate. We leapt at the possibility of another destiny, escaping from that hellish laboratory where we’d been used as ideological guinea pigs. The revolution that promised redemption had turned us into suspects for our love of freedom, and our only way out was to flee toward it.

In the country that welcomed us, we were finally able to breathe without fear, rebuild our lives, and recover the dreams they had tried to steal from us. We weren’t traitors or deserters: we were survivors of a utopia that had become a prison. And although exile brought its own wounds, it also gave us the opportunity to recount what we had experienced, to turn pain into memory and memory into testimony. Because if we learned anything during those years of repression, it was that freedom is not begged for: it is won, defended, and honored by telling the truth.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.