Alejandro González Acosta, 1 December 2017, Mexico City — Lichi[1] told me that the last time he was in Cuba[2], he went to visit a G-2 colonel at home, the brother of a famous Cuban historian who was Lichi’s good friend in Mexico. Between drinks and confidences, Lichi asked him:

“Come on, man, just between us: You’re surely watching me and having me cableao[3] [listened to] everywhere, right?”

“No, Lichi,” the other responded. “There’s no need because we already know how you think, even what you publish. In addition,” added the security officer, “we don’t have the technology[4] we used to have when the bolos[5] were here. There’s not much left that’s in good working order. And the little we have is directed toward the Central Committee of the Communist Party, because we’re interested in knowing what they’re thinking and planning.”

Perhaps this was just another one of Lichi’s many fictions, but I suspect that this one was true.

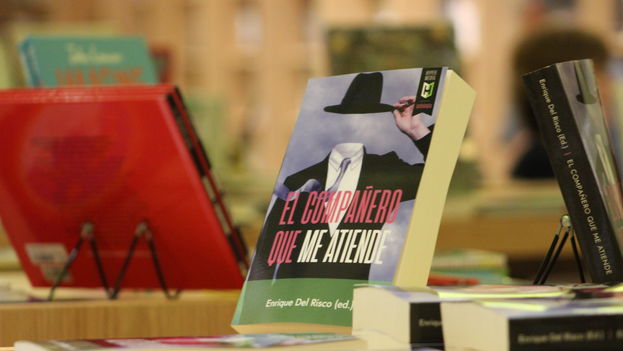

It makes me think of the anecdote that was recently published in El compañero que me atiende [The “Compañero” Who Looks After Me] (Hypermedia, 2017), the timely anthology that Enrique del Risco (“Enrisco” to his friends), an exiled Cuban historian in New York, compiled and edited.

Like so many other common expressions on the island, this title probably isn’t fully understood by someone who isn’t Cuban and hasn’t passed at least a part of his life in Cuba during the last 60 years. “The compañero who looks after me” can be, for foreigners, a waiter, a mechanic, some employee, who with kind and fraternal camaraderie procures some service or product for them. But we Cubans know that’s not the case: far from it.

Just like the “accomplishments” of the Cuban Revolution that were showcased with pride—every child would have education and every sick person his doctor—so every citizen can count on having his own policeman, solicitous and attentive to what he says, hears and thinks. This ubiquitous and omnipresent character, almost omniscient and supposedly omnipotent is, ultimately, “the compañero who looks after me.” In a totalitarian system like the present Cuban one, where “everything not prohibited is obligatory,” it’s normal that half the population monitors the other half, and even among that half, nothing escapes them.

Something really monstrous that escapes the comprehension of the rest of the “normal” world (Cuban hasn’t been a “normal” country for a long time) is that this “compañero who looks after me” has in turn his own “compañero who looks after him,” and this one possesses another “compañero who looks after him,” in an uninterrupted and infinite succession until you come to the top of the pyramid where that Big Brother who monitors everyone and perhaps even himself is busy looking suspiciously into a mirror of informers. Everything is possible in that surrealistic Caribbean world.

Enrique del Risco understands this perfectly, and thus gives his pertinent commentary about The Trial and The Castle, written by the famous and prophetic Czech author, which he includes in his preface. It’s been said—and it’s no joke—that “if Kafka had been born in Cuba, he would have been a genre writer.” For modern Cubans, The Trial and The Castle have a solid and macabre arquitectonic symbol: Villa Marista, the “home sweet home” of all the compañeros who look after us.

If anybody knows this theme of a “compañero who looks after me” it was Lichi. His famous Informe contra mí mismo (Informing Against Myself) is nothing more than the response, after years of boredom, that he gave to the seguroso [State Security officer] who was trying to get him to inform on his own family.

This matter of citizen spying is almost a genre of opposition Cuban literature: Antes que anochezca (Before Night Falls), by Reinaldo Arenas, would be another response to that “compañero who looks after me.” And Contra toda esperanza (Against All Hope), by Armando Valladares, also. And En Cuba Todo el mundo canta (In Cuba Everybody Sings), by Rafael E. Saumell. And Fuera del juego (Out of the Game), although you would have to say here “the compañero who takes of ‘us’,” since it should include his then-wife, the poetess Belkis Cusa Malé; En mi jardín pastan los héroes (Heroes Graze in My Garden); La mala memoria (Bad Memory), by Heberto Padilla; Mapa dibujado por un espía (Map Drawn by a Spy), by Guillermo Cabrera Infante; La nada cotidiana (The Daily Nothingness); La hija del embajador (The Ambassador’s Daughter); La noche al revés (Night in Reverse), by Zoé Valdés; and 20 años y 40 días (Twenty Years and Forty Days), by Jorge Valls. Even El hombre que amaba los perros (The Man Who Loved Dogs), by Leonardo Padura, is, in its own way, also a novel about permanent vigilance.

For Cubans of this epoch, the Forest of Eyes in Alice in Wondertown is a reality with nothing imaginative about it: Everything is seen and known in this total fortress that is the Cuba of the Castros. Thus, this work of Lewis Carroll served Jesús Díaz for his brilliant interpretation of Alice in Wondertown (1991), with a characterization of the unforgettable Reynaldo Miravalles in the powerless role of the Director of the Sanatorio Satán (Satanic Sanitorium) in the town of Maravillas de Noveras, with his bony accusing finger, descending from the heavens in the rattling elevator.

A little before, Díaz had managed—finally!—to publish his unforgettable novel, Las iniciales de la tierra (The Beginnings of the Earth), where the protagonist Carlos Pérez Cifredo confronts another variant of the “compañero who looks after me”: the interminable autobiographical document that so many Cubans have written, the famous cuéntame tu vida (Tell me about your life), the implacable and intrusive spreadsheet of entry to a political organization. This can also be considered a parallel genre to what Del Risco puts forth later. In some place on the island—perhaps in the Villa Marista—there must be an enormous archive with all the “tellmeaboutyourlife” stories that have been written in these almost 60 years. A Library of Babel of denouncements and, worse even, self-denouncements, saved for memory, disgust and posterity. We should then have a new V. Chentalinski to do with this what he did with The Literary Archives of the KGB.

We can’t deny it: The German film The Life of Others and Kundera’s The Joke are, for Cubans, part of a vital daily bibliography, a kind of Caribbean self-help literature, and this book confirms it. But wise friends are warning me that these references should also include classics like The Rebel, by Camus, and The Captive Mind, by Milosz.

Fifty-seven living authors participate in this “work of multiple creation,” all of them Cuban, the majority outside the island, but also some who live there, for whom the very fact of publishing in this book could have serious consequences—at the very least, a friendly visit from “the compañero who still takes care of them.” There are 57 testimonials, but there could also be 11,616,004 (the total population of Cuba according to the last official 2017 census), since all have, had or will have a similar story (without counting the 2,000,000 in exile). And all the Cubans dispersed throughout this broad and alien world since 1959 have at least one anecdote about that solicitous companion of our terrors and fears.

But let’s not be naive: The perversity of this system is not limited to Cubans alone. Everyone on the island is suspect, even if the opposite is proven. Correspondents and foreign diplomats also have their “compañero who looks after them,” although organized under other façades: the International Press Center, first, and the General Protocol Directorate, second, both camouflaged under the cover of the Ministry of Foreign Relations.

And vigilant attention is not limited to Cubans on the island, either. In the Exterior, they also continue being the object of the watchful supervision that is organized from the Regime’s embassies, always scandalously overpopulated and with an intense espionage activity, under the façade of the Chancellery, supported by that large Ministry of Exterior Police that is the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the People.

Thus, this book is fully registered in the testimonial genre that the Cuban Revolution gave birth to itself, in works like Operación Masacre [Operation Massacre], Trelew [Trelew], and many more, but from the other camp, the other side of the door… or the wall. Although the official “critics” say that if testimony is not “progressive, revolutionary and committed” it is not testimony, Reality contradicts them. In fact, today the testimony of the victims of communist repression is much more alive and convincing than that of the repressors who are determined to deny it or misrepresent it.

The intellectual who is monitored and persecuted in Cuba has been around for a long time. Convinced that they were harassing him, Manuel Zequeira pretended to make himself invisible by putting on a sombrero. José María Heredia left the country disguised as a sailor, an authentic proto-balsero, fleeing from the police. José Jacinto Milanés ended his days in a mental hospital, in a fog of paranoia. José Martí traveled to Cuba as “Julián Pérez” in order to outwit the pre-Castro customs and immigration. Virgilio Piñera was permanently obsessed with “an old panic,” expecting them to come for him. Raúl Hernández Novas, in spite of going about hunched over, couldn’t really hide himself because he was very tall. He committed suicide after experiencing “the enigma of waters,” and he rushed headlong—da capo—to a liberating death.

A typical Cuban feels himself permanently under surveillance. Even when he finally manages to escape the island-prison, for a long time he searches for microphones in lamps and underneath tables if some unwary person asks him something he considers compromising. He never says what he thinks, because he knows very well the price he will pay. He’s been trained. Later he loosens up and even talks too much: Some joke that they pay him to talk and then pay him more to shut up.

The image of a guard holding a sharp, threatening machete and a wide-open eye, watchful and omnipresent like something out of Santería, are the symbols of the CDRs (Committees for the Defense of the Revolution), the most pernicious, corrupting and demeaning of all the gruesome inventions on the Island of Doctor Castro.

I’m listening to you, whispers the emblem. Without knowing it, those frustrated old ladies, bitter and needing to feel they’re useful for something, the classic cederistas, are the descendants of the Parisian Bluestockings of the Place de Grève and the fisherwomen of the Marais. They are not named Charolotte or Lisette, but rather “Cusa of the Committee.” What the hell!

A joke about the government can be fatal. In my time, among friends, as an exculpatory and prophylactic exorcism, expecting the presence of microphones—or people with the same mission—after hearing a “joke against the government” we would finish roaring with laughter with a sentence: “On the record: If I’m laughing it’s because of indignation.” And in Cuba, even when we hung up the phone, it listened to whatever was said nearby, an old tactic from the NKVD and the KGB.

A person who is very dear to me lost his promising career as an economist because he told a joke about Nicolás Guillén with a mocking version of his poem, Tengo, in a group of supposed friends, and one of them ran to inform the Cuban Securitate, who expelled him from the University of Havana. Everything culminated in a grotesque scene: the then Rector (Reptile) obliterated him with a critical sentence: “Between doubt and the Revolution, I stand with the Revolution.” Later, this same rector was gloriously dethroned: Such is life in these tropics, dearest. Because the best thing about this story is that the earth is round (although some nuts still doubt it) and continues to turn….

The deeply religious mentality of communism, and especially that of the two former students of schools that were directed by severe priests, as were Stalin (in a seminary) and Castro (in the Ignatius College of Belén), creates a system of constant “examination of conscience,” of which “the compañero who looks after us” is a fortunate confessor in civil clothing. These “castles of the soul” and the Marxist-Ignacius “spiritual exercises” that culminate in the famous auto-criticism (much better and more effective if it is public and humiliating), are part of a process of continual and interminable catechism and purification. Everyone needs to be reviewed periodically, and in this way, one is offered the generous possibility of “repentance.” What is not pardonable is to decline the confession and the auto-inculpation, and even less to persevere in the error with the disastrous bourgeois “auto-sufficiency” that opposes accepting the charges and sins….

One thing that is especially perverse about this “head police” is that, against every presumption, it doesn’t hide; on the contrary, it is shameless. It exposes itself; it demonstrates that it’s always present and that it’s everywhere, because its principal mission, in addition to causing fear, is to dissuade and advise—lovingly and persuasively—almost like a friend: “Don’t burn yourself, dude.” “Don’t create problems.” “I understand you, compadre, but….” It is, let’s say, a kindly, sensitive executioner, almost deliquescent and ethereal. A “guardian angel” in shirt sleeves, who not only can expel you from Paradise but also put you in prison, which is Purgatory or Hell, depending on the sentence.

Enrique del Risco aptly baptizes it Género totalitario policíaco, the totalitarian police genus. It could also be a species of communist bildungsroman, a kind of Cuban formative novel, the “sentimental education” of the “new man.” Or also police eschatology, because of the persistent phantom who always is persecuting you. Or the neo-Gothic novel of castrismo, with its horrendous monsters. Or comic surrealism. A chance Orwellian 1984 but in the continuous indicative present, up to date, 2017.

The kindness of “the compañero who looks after you” goes in two directions: to control and support you, but also to look for your cooperation, to convert you from being someone suspicious to being an informer. Because creating a snitch is the jewel in the crown for the compañero, and there are many who have been persuaded and are now limping along this path.

Informing has been presented historically as a “revolutionary virtue” from a very old date. In the Soviet Union of Stalin the example of the little pioneer, Pavlik Morózov (1918-1932) was very popular. In a supreme surge of generous militant communism, he denounced his parents and grandparents, who were executed. Then he died, according to the propaganda, assassinated by other vengeful family members, but the latest research in the KGB archives allowed Catriona Kelly to make sure in her book, Comrade Pavlik: The Rise and Fall of a Soviet Boy Hero (2005), that apparently it was the “compañero who looked after him” who liquidated the talkative Pavlik, following higher orders, in order to later dedicate to him statues, books, songs, a symphonic poem, opera and even a movie by the laureate, Sergei Eisenstein (Bezhin Meadow, 1937). This should serve as a wise warning to incautious collaborators that their task is extremely dangerous, not only for their victims, but also for the compañeros themselves. “If there were no heroes, you would have to invent them, whatever the price.” So said the good Koba behind his smoking pipe.

One of the most diabolical perversions of the system is that, in addition to having a mandatory Identity Card, every citizen has a File, but unlike the first, which he must always carry, he never sees the second, although it decides his life the whole time: whether he progresses or not, if he makes progress or fails, if he goes forward or falls back, if he lives or not. And this file has a permanent, dedicated scribe, who is, precisely, the compañero, that “annihilating angel” who doesn’t miss a step or a footfall, a bloodhound always sniffing your tracks, that devoted scribe who writes your Book of Life.

In the twisted, repressive logic of Communism, everyone is guilty and thus punishable. If we are alive, of course we’re committing some sin and various crimes. It’s only a matter of finding out. Therefore, if the Power decides to investigate your life, it will always find something for which to blame and punish you. And if nothing appears, it’s invented: Ángel Santiesteban knows something about this.

It’s a shame that Fidel Castro wasn’t able to read this book, which has him in it as a permanent presence. I imagine he would have enjoyed it a lot, because he would have recognized his most transcendent work. He was fortunate to have a long, although sterile, life, always surrounded by the veneration and obsequiousness of his terrified close friends, and he surely would have enjoyed knowing about the creativity of his subordinates to whom he delegated the honorable task of being vigilantes, in that government that’s a carbon copy of Minority Report, constructed “with the delight of an artist.” The ideal for him was that everyone carry his own vigilante inside, a kind of tortuous doppelgänger or devious old uncle, embedded in the subconscious. This compañero is, therefore, a kind of vampire, insatiable and contaminating. After sucking your blood, he prolongs your life, but also makes it impure, in his image, like his spawn.

But I have a terrible suspicion: In reality, the system and its agents are not really worried about what people think, but rather what they say and do. It’s a kind of tacit complicity that although they imagine, suppose and even know what you think, what really matters is what you do and say, obliging people to act falsely without a break, in a permanent performance, a schizoid, never-ending performance, with an irreparable psychic dissociation which forms the character of the present “new man”: “I know that you don’t like me, but what’s important is that you obey and venerate me.”

Without doubt, one of the most cruelly delicious and masochistic experiences will be when this nightmare regime finally collapses, and people can read the bulging files (that I hope they don’t destroy in their precipitous fall), guarded by State Security, the grand fabric of the “compañeros that take care of us.” I trust that they won’t eliminate them because I know that, perversely, they would want to leave the seed of discord to be sown for 100 more years. But, finally, with the sad truth would come mental, social and individual health. “In 100 years,” said the French aristocrat while he climbed the stairs to the guillotine that awaited him, sharp and thirsty, “all this will be only an anecdote.”

This “compañero who takes care of us” is also a character out of cinema, a comedian in a guayabera or safari outfit, with pockets full of pens and pants, with one pant-leg carelessly but elegantly tucked into a boot. Don’t forget that the dark glasses are an essential part of the image. He deserves a movie that would be shown in festivals of horror films and involuntary humor, like the series Mobil 8 and Sector 40, with that sinister and mocking “Manquito” chasing us everywhere.

You would have to expect now the passionate testimony of the other side, written by them; it could be entitled The Compañeros Who Served, where the magnificent influence that the ones watched had on the vigilantes would be appreciated, obligating them to read philosophy, history and art, and even listen to curta music, in order to understand and be able to monitor their prey better. Such a grand cultural level they would attain thanks to that! Because, let’s not forget—supreme irony—they also have been permanently monitored by their own “compañeros who look after” them.

But the “compañeros who look after you” have also been good teachers and have educated outstanding disciples, and now their presence is not required, since their pupils have become very capable themselves. The cultural officials—Barnet, Prieto, Arrufat and several others—are already so good at that Dark Trade as were in their time the “compañeros who looked after them.” You can’t deny that they had excellent teachers and became magnificent students.

Those “attentive compañeros” have been the same “literary advisers,” “curators of exhibitions,” “vigilant publishers,” “omnipotent and decisive jurors of literary competitions,”… truly protean and know-it-all. And, in addition, very proud of their mission. I remember a famous painter and graphic designer, who proclaimed cheerfully and loudly that he was a “trumpet,” meaning a snitch on his colleagues, for which he was compensated and decorated with the Medal for the Twentieth Anniversary of the Ministry of the Interior. It’s the small vanity of the miserable, the joy he couldn’t hide for this variant of ideological bullying, a surprising cross between a cat and a rat.

If anyone inside this genre merits that a novel be written about him, it would be José Abrantes, perhaps the most dramatic figure in recent times in terms of the artistic tension of conflicts. Possibly someday one of his descendants will decide to write it, since the former Minister was the first instructor and creator of the “compañeros who looked after,” before being looked after himself by his trained trainees.

Although they often are solitary, the “compañeros who look after” can operate in harmonious duos, not at the same time but rather successively: First Good Cop appears, and if you don’t understand the lesson, Bad Cop shows up. Or the opposite, according to the individual. But they’re well distributed, coordinated and organized. They’re a didactic couple, in the purest Makarenko style: all a pedagogic poem. They’re the Stakhanovites of culture and thought, the Lunacharskys of ideas, the Dzerzhinskys of metaphors. In sum: the Dear Enemy.

Enrique del Risco qualifies this large anthology as an anomaly, because the genre obviously will not enjoy commercial success in countries where it’s a living reality, since it belongs to the “literature that is rigorously monitored,” and also because—for understandable mental health reasons—it doesn’t want to be remembered or revived in a society where it has already been eradicated. Thus, it is a thankless and upsetting genre, but one that is necessary so that the experience will not be repeated. This anthology-book (in both meanings) is, then, a text that is not only literary and historic, but also informative and educative. It constitutes a whole Practical Manual of Totalitarian Teaching that is operational. If only for this reason, it deserves to be widely read. Perhaps it would serve others to know—although no one learns through others’ experience—what Cubans have gone through and already suffered (and continue to suffer): those beings that are happy, unworried, playful and always under suspicion, Cortázar’s anxious cronopios and esperanzas, permanently monitored by severe famas.

This book is, on the other hand, a work of catharsis and exorcism, and it could be the genuine Book of Text of the Grand Ministry of Social and Political Domestication. It also can have another use: showing the interior mechanisms of spying and snitching, and it can be an antidote and a preventive prophylactic, with recipes that the great artistic maestros elaborated from their unhappy personal experience of evading, confounding and deceiving that vigilante, that monstrous euphemism that is needed to “look after us,” in order to survive as an efficient and productive element of a dreadful mechanism. This book, possibly, is a collection of recipes to neutralize it.

[1] Eliseo Alberto de Diego García-Marruz (Arroyo Naranjo, September 10, 1951, Mexico City, July 31, 2011).

[2] The last time he was alive. Later he returned, now cremated into “beloved ashes,” to fulfill his wish to be scattered on the murky waters of the river near the home of his birth, by his Herculean twin sister, Fefé (Josefina de Diego), his striking daughter, María José, and a group of close friends.

[3] With hidden microphones.

[4] The technology, equipment, microphones.

[5] Russians.