![]() 14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 12 June 2017 — His mother died, his brother emigrated and now no one brings flowers to the tomb of one of those many young Cubans who lost their lives on the African plains. His death served to build the authoritarian regime of José Eduardo dos Santos in Angola, a caudillo who, since 1979, has held in his fist a nation of enormous resources and few freedoms.

14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 12 June 2017 — His mother died, his brother emigrated and now no one brings flowers to the tomb of one of those many young Cubans who lost their lives on the African plains. His death served to build the authoritarian regime of José Eduardo dos Santos in Angola, a caudillo who, since 1979, has held in his fist a nation of enormous resources and few freedoms.

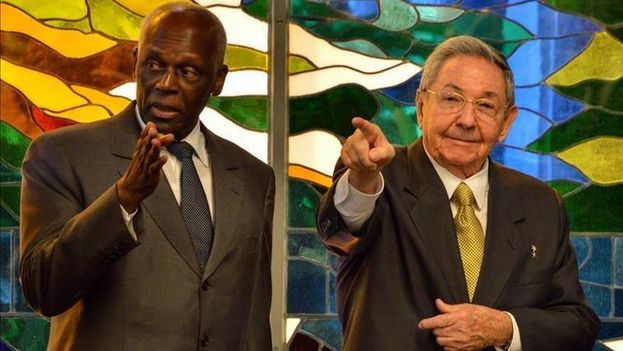

At 74, Dos Santos knows the end is near. His health has deteriorated in recent months and he has announced that he will withdraw from politics in 2018, the same year that Raul Castro will leave the presidency of the Cuba. Both intend to leave their succession firmly in place, to protect their respective clans and to avoid ending up in court.

For decades, the two leaders have supported each other in international forums and maintained close co-operation. They are united by their history of collaboration – with more than 300,000 Cubans deployed in Angolan territory during the civil war, financed and armed by the Soviet Union – but also connected by their antidemocratic approach.

Longevity in their positions is another of the commonalities between Castro and Dos Santos.

The Angolan, nicknamed Zedu, is an “illustrious” member of the club of African caudillos who continue to cling to power. A group that includes men like the disgraceful Robert Mugabe, who has led Zimbabwe for 37 years, and Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has governed for almost 38 years Equatorial Guinea.

Their counterpart on the Island surpasses them, having spent almost six decades in the control room of the Plaza of the Revolution Square, as a minister of the Armed Forces or, following his brother’s illness, as president. Neither Zedu nor Castro tolerate political opposition and both have fiercely suppressed any dissent.

Angolans also live amidst the omnipresence of the royal family. On the banknotes, the face of Dos Santos shares space with that of Agostinho Neto, and in political propaganda he is represented as the savior of the country. One of the many tricks of populist systems, but very far from reality.

What has really happened is that the family and the African president’s closest allies have made colossal fortunes. The largest oil exports in Africa today have fueled this oligarchy, which, ironically, was built on the efforts of thousands of Cubans who left their lives or sanity in that country.

Isabel dos Santos, nicknamed by her compatriots the Princess, has wasted no time in taking advantage of the prerogatives that her father grants her. Forbes magazine calls her the richest woman in Africa, with a fortune of around 3.1 billion dollars, and last year she was named head of the state-owned oil company Sonangol, the country’s most important economic pillar. She also controls the phone company, Unitel.

She resembles Raul Castro’s daughter Mariela in her taste for giving statements to the foreign media and presenting herself as someone who has achieved everything “by her own efforts.” She projects an image of a modern and cosmopolitan businesswoman, but all her businesses prosper thanks to the privileges she enjoys as the daughter of her father.

Her brother, José Filomeno de Sousa dos Santos, also economically advantaged, sits at the head of the Angolan sovereign fund that manages 5 billion dollars. An emulator of Alejandro Castro Espín, whom many credit for the impressive voracity that has led the Cuban military to seize sectors such as hotel management.

However, Zedu has preferred to choose a puppet as heir to the post of president and head of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA): Angola’s Defense Minister, João Manuel Gonçalves Lourenço. A figure who will be the public face while the true dauphins try to continue sucking dry – like voracious leeches – the resources of a country that is not experiencing good times.

Gonçalves Lourenço is seen as a moderate, as is his emulator in Cuba, first vice-president Miguel Díaz-Canal. Men who will try to give a face-lift to personality-centered systems to silence the voices of those who assert that the “historical generation” does not want to abandon power. Neither has been chosen for his abilities, but rather for his reliability and meekness.

Gonzalves arrived in Havana in mid-May with a message from President Dos Santos to Raul Castro. In Angola, 4,000 Cubans work in sectors such as healthcare, education, sports, agriculture, science and technology, energy and mines. It is one of the countries that most appeals to the Island’s professionals for the personal economic advantages that serving on an “internationalist mission” there affords them.

Gonzalves’ trip, of course, also included a commitment to continue to support the Island, perhaps with some promise of credit or oil aid to ease Cuba’s currently complicated situation. Most likely the heir to the throne came to tell the aging monarch not to worry, that Angola will continue to count itself among its allies. They are words that could be blown away in the wind before the uncertain future that awaits both countries.

For years the Angolan regime benefited from significant foreign investment and high oil prices, the main source of income. However, the fall in the value of crude oil in the international market has complicated the day-to-day situation of citizens subject to economic cuts, a rise in the cost of living and a decline in public investment. The discontent is palpable.

On the Island, not a week goes by without an obituary reminding us of the reality that the “historical” generation is dying off. The brakes are about to be applied to the thaw with the United States, and the mammoth state apparatus isn’t about to adapt itself to the new times. The double standard, corruption and diversion of resources undermines everything.

Neither Castro nor Dos Santos will leave power in the context they dreamed of. One falls ill, after having negated in practice his ideological roots, and senses that history will destroy his supposed legacy. The other loses control over Venezuela, that mine of resources that prolonged the life of Castroism. His worst nightmare is that young Cubans care more about Game of Thrones than the revolutionary epic.