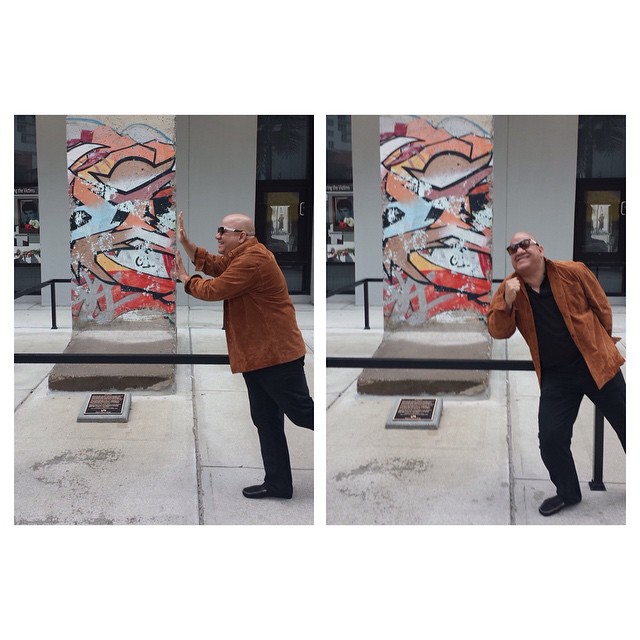

Twenty-five years later some people are still trying to knock down a piece of the Berlin Wall.

On November 9 and 10, 1989 Germany experienced an event that quickly and with just enough lubrication sent the rusty wheel of history spinning. It was an event that marked the beginning of the end of European socialism: the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Such a seminal event did not come out of nowhere. It was not a coincidence nor did it happen spontaneously. There were events leading up to it.

Protests were growing in Leipzig, Dresden, East Berlin and other cities demanding democratic change. The government of the former German Democratic Republic was unable to cope with the ever growing number of its citizens fleeing to Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin.

Looking for a way to ease the pressure of an untenable situation, on May 2 of that year a group of Hungarian soldiers dismantled the barriers at the border with Austria and for the first time opened the door to the free world, allowing Germans to flee west through Hungary.

But rather than serving as a release valve, it turned out to be a boomerang. Popular discontent grew in breadth and scope. By October a revolution seemed imminent.

Faced with tangible indications of the beginning of a mass exodus and widespread social unrest, the members of the Council of Ministers were forced to resign. A couple of days later the borders separating the two Germanys and the two Berlins lost their reason for being.

This event and everything that followed were historic. There were also consequences for German unity, for employment, subsidies and the retirement age.

When the archives are opened, which will one day happen, we will be able to delve into and fully analyze the reasons why the roar of communism’s collapse did not create a tsunami in Havana.

During that time Cuba’s leaders certainly were not bothering to hold meetings. As never before, the state and government were subject to the rulings of the Communist Party.

On Fidel Castro’s orders, and without protest or any opportunity to question, an already fragmenting society was shattered to pieces. Propaganda strategies were devised to neutralize opinions coming from the other side and filtering out of Cuba. Warnings were issued and limits were set on free expression.

The ghosts of loneliness, of war and stoicism became the fuel that provided justification for the shift of the nation’s economic development into reverse, which in turn attracted cash and sympathy from overseas Cubans who, as was reasonable to expect, rushed to lend aid to family and friends living on the island.

It is virtually impossible to imagine that at any given moment a massive social uprising would occur in light of the aid coming from family members and because the stagnant economy forced many Cubans to adapt to circumstances.

The government used cunning to alter people’s better judgement. Twenty-five long years have passed since that event and Cuba’s dictatorship is still in place. Isn’t it about time to change strategy?

21 November 2014