Last February 6th a note was posted on the digital space Cubanet regarding a TV Martí interview with Lech Walesa, the renowned Polish trade union leader and undisputed trailblazer of the democratic transition in his country, during his recent visit to Miami. This note summarizes some thoughts Walesa put forth apropos freedom in Cuba and the role of the internal opposition on the island, which has caused mixed reactions among some members of Cuban dissident groups.

Last February 6th a note was posted on the digital space Cubanet regarding a TV Martí interview with Lech Walesa, the renowned Polish trade union leader and undisputed trailblazer of the democratic transition in his country, during his recent visit to Miami. This note summarizes some thoughts Walesa put forth apropos freedom in Cuba and the role of the internal opposition on the island, which has caused mixed reactions among some members of Cuban dissident groups.

Overall, we may or may not be in agreement with Walesa’s opinions, but I don’t think that his interests were particularly directed at mocking the dissidents. This is not an exceptional event either: with regard to the review of the situation in Cuba we know that from time to time someone appears who “knows” better than we do what must be done to end the dictatorship. Interestingly, that someone is seldom a Cuban.

But the matter comes up repeatedly, and this case brings with it other lessons, since the person rendering opinions is a recognized international leader, which implies that he enjoys the self-assurance of authority, in virtue of which his opinions may be assumed by others as absolute truths, or, at least, accepted as priori judgments. continue reading

That is why, at the risk of upsetting those who worship the sacred cows of politics and, at the same time, favoring my admiration and respect for Walesa’s extraordinary merits and leadership in the democratic transition of his country, I want to go over his words and discuss them on a personal level. I’m barely one among the thousands of Cubans who nurture independent civic organizations in Cuba, but every citizen is a political subject -even those who are not aware of it- and each individual’s opinion is worth, at least, as much as that of the most prominent leaders.

I do not think, however, that Walesa’s role in Poland’s recent history turn him into a de facto “expert opinion” to assess the Cuban case. In fact, his opinions display great ignorance about Cuba’s situation, about the nature of totalitarian power and about our history and idiosyncrasy.

I seem to feel a certain degree of arrogance, or perhaps a tad personal vanity in the phrase “I tried to give advice to the Cuban opposition but, for some reason, they won’t listen to me”. Without wishing to dismiss the value of Walesa’s political experience, I am not aware that anyone, in the name of the opposition here, has asked him for advice. His position is, as it were, the authoritarian father’s punishment towards a misbehaving child who does not follow the rules, and I must confess that -far from bothering me as a member of the Cuban opposition- at first I thought it even funny: Democratic Cuban colleagues, let’s not toil any more in our long resistance against the regime, we only have to follow Walesa’s advice!

Having said that, in a debate mode, I would like to know how the Polish leader could have commanded such a powerful syndicate as Solidarity in Cuba; a country in which the very government took it upon itself to terminate almost to the core the port movement, plus swept off all which once was industry. Mr. Walesa seems to have no idea that there are no laborers on this Island, only those who survive in the few sugar mills or in the very few shops or factories that have withstood the destructive power of the regime. We don’t have great trade to encourage the existence of port syndicate activity. We can’t begin to compare Casablanca, the modest shipyard in Havana bay with the gigantic complex of shipyards in Gdansk, with thousands of workers, the critical main stage of the Polish transition. Cubans don’t even have a merchant or fishing fleet.

There are only minor vestiges remaining in Cuba of those great cigar factories that were the cradle and the kiln of Cuban syndicalism between the end of the XIX and the beginning of the XX century. How could labor unionism and a labor leader exist in a country without a labor force where the government lays off 20% of the active labor force without a second thought? And we are not just talking about unions: here, even mere free association is taboo, because, while Cubans have not historically been strong carriers of civic traditions, the Castro dictatorship undertook to void any possibility of social autonomy from the first years following the seizure of power in 1959.

It seems unreasonable to move mimetically the experiences of a process of transition from one nation to another. The Cuban situation is neither better nor worse than that of Poland at that moment. It is simply different. It’s enough to remember that in the political arena, the Polish opposition was able to count on the firm support of such an ionic figure as that of Karol Jozef Wojtyla, Pope John Paul II, and the Catholic faith constituted a unifying element of the spirit of the Polish people towards democracy, which –coupled with a long tradition of struggle for independence and a solid civic culture- contributed decisively to the opposition’s victory. The struggle, in addition, not only went against a puppet government, but ultimately against a foreign power, the Soviet Union, at a time when the tensions of the Cold War were being undermined by the collapse of the East European communist models. So, at the end of the decade of the 80’s all factors came together which, taken together, led to the transition to democracy not only in Poland but in all the countries of the former socialist bloc.

Cuba, on the other hand, shows a very different scenario, though there are common elements in our circumstances of transition, such as the existence of a regime calling itself “communist” and a centralized power that controls the economy, the politics, the military, the enforcement agencies and the social structures. The fight is against a national dictatorship that has gone through several phases over half a century, including satellite status of that same Soviet power.

For its part, the Cuban Catholic Church is far from having a close relationship with most of society, but we must recognize the (local) civic community work of many priests in many parishes. We need to understand that we Cubans, in general, are not very zealous in matters of faith, and that the best known national paradigm of spiritual unity, José Martí, has been widely manipulated and quasi-prostituted from all ideologies and interests. As for the leadership of the religious institution, it is a very distant elite, very far from the politics of change that are evolving from independent civil society and the opposition. We have a Church of spiritual formalities not truly committed to the struggle of resistance. In fact, its tendency has been to fold under the power of the ruling autocracy.

I don’t think it’s a problem that there are “too many leaders within the opposition” in Cuba and no one among them who is “strong enough” to lead all of us. Actually, I think the variety of ideas and projects that exists suggests the possibility that one day we will have to choose among many proposals. Variety does not necessarily mean “disunity”, as shown by the trend of mutual support that has been occurring in recent years between different projects and teams. Perhaps the diversity -not “disunity”- is precisely the most practical and possible strategy in a country where power has cornered every area of society, including families.

Thus, operating as small cells and concurring on greater common endeavors, dissidence is uniting to meet the changes of the Cuban transition. Today we perceive many open fronts of the civil resistance inside Cuba that include both so-called traditional opposition parties, such as the independent press in all its forms and multiple civil society projects, which have demonstrated they are capable of collaborating with each other and of promoting common approaches, regardless of their ideologies. If that process is ever consolidated, or if it succeeds, the future will tell, but, at any rate, the variety of the Cuban opposition spectrum, far from making me worry, seems to me like a reflection of democracy in its midst, an idea which is shared by many representatives of the dissidence. At any rate, magnifying the advantages of what it insistently being called a “union” is as harmful to the opposition as it is opportune to the dictatorship.

We don’t need to found a monolithic union around a “powerful” single leader in order to reach democracy in Cuba (we have had too much of that in the last 54 years). In any case, the power of the Cuban dictatorship has been so complete that any action that appears will constitute an important factor to undermine the system without necessarily having to be subordinated to a particular leader. Experience shows that the power of a leader lies not only in his ability to summon, but in a combination of many factors, among which, his capacity to act is essential. Today, the actions of several local and regional opposition organizations are showing both their ability to fight and the summoning power of their leaders.

Another one of Walesa’s statements demonstrating his ignorance of the Cuban situation is one in which he said that “in cities and towns and people should have offered to fill new positions, new duties already, in the transformed situation. In two years, there will be democratic elections (in Cuba)… we have to be prepared, because what will happen after the fall of the Castro regime will be chaos”.

I would dare say that in almost every city and town in Cuba social actors do exist who will play an important role in the zero hour, i.e., at the moment of time of the definitive changes, and, at every instance, there will be many more. The government’s inability to overcome the structural crisis of the system is, paradoxically, the main source of the general desire for change. Certainly, the Cuban transition has already begun and the system began in a process of erosion years ago that has been accentuating gradually, but permanently. However, reality still has not been processed to the point that it is possible to occupy the posts of local governments and participate in decision-making from legal structures that are strategically designed to avoid such an occurrence. Maybe not even our changes will take place that way.

No one knows if in just two years there will be democratic elections in Cuba, though I hope so. But I can assure Walesa that, by then, there will be more Cubans, today’s opposition and citizens of that near tomorrow, who will be prepared to meet the challenges of democracy after more than half a century of totalitarianism. We are striving for that.

Personally, I appreciate the good wishes for our country’s freedom expressed by the Polish trade union leader, but he really does us a disservice when lending himself to coin such a cliché. I also reject the dire predictions of social catastrophism: there will be no such chaos in Cuba because, at that moment, above all our differences and reservations, the love for our nation will be asserted among us, the will to rebuild on the ruins and the experience gained by several generations during long years of struggle, to finally found institutions that will prevent the return of a dictatorship. Believe me, Mr. Walesa, on these pillars will be born a most enduring union, not of the opposition, but of all Cubans.

Miriam Celaya

Translated by Norma Whiting

(Article originally published in Cubanet on February 22, 2013)

February 27 2013

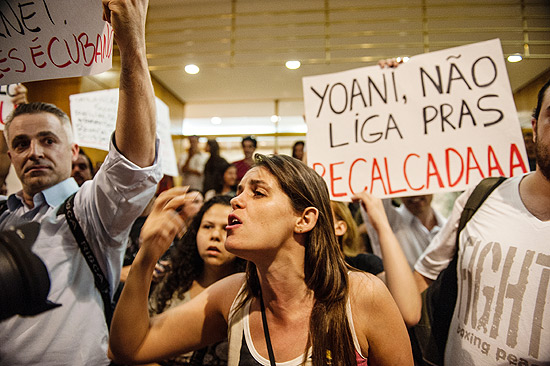

The villainy of “Feria de Santana” was executed also against one of the most loved and respected senators among Brazilian politicians, Eduardo Suplicy, with recognized militancy on the left, the objects of insults and disrespect from the bloodthirsty mob. What happened was an act of unacceptable intolerance, not only against an supposed “CIA agent” blogger, as they wanted to see it, but an attempt by a foreign country (the Cuban government) to define the course of internal policy South American giant.

The villainy of “Feria de Santana” was executed also against one of the most loved and respected senators among Brazilian politicians, Eduardo Suplicy, with recognized militancy on the left, the objects of insults and disrespect from the bloodthirsty mob. What happened was an act of unacceptable intolerance, not only against an supposed “CIA agent” blogger, as they wanted to see it, but an attempt by a foreign country (the Cuban government) to define the course of internal policy South American giant.

following presentations had the simple and only objective of hearing what she had to say about a wide range of topics, all focused on an island greatly loved by Brazilians of all stripes: Cuba. After that first night of intolerance, overcome by the courage of the blogger and the support of senator Suplicy, Yoani was offered dinner at the residence of one of the organizers of the activities in the city, where the Cuban blogger shared the evening with Senator Suplicy, an important participant in the acts of that day, founder and leading member of the Brazilian Labor Party, as is well-known. Yoani and Suplicy spoke at length.

following presentations had the simple and only objective of hearing what she had to say about a wide range of topics, all focused on an island greatly loved by Brazilians of all stripes: Cuba. After that first night of intolerance, overcome by the courage of the blogger and the support of senator Suplicy, Yoani was offered dinner at the residence of one of the organizers of the activities in the city, where the Cuban blogger shared the evening with Senator Suplicy, an important participant in the acts of that day, founder and leading member of the Brazilian Labor Party, as is well-known. Yoani and Suplicy spoke at length.

My trip to Prague is funded by Amnesty International, because I was invited as a juror for a film festival they organized. I will go to Italy to collect an award that I had not been allowed to collect, which included–at that time–the plane ticket. From Italy I will go to Spain for the El Pais award, which also includes airfare. From Spain I go to New York, by invitation of students from two universities, which offer courses on computer science. From NY I will go to Miami to visit my sister, with airfare paid for with her money. From Miami I am going to Mexico to a meeting of the Inter American Press Association, IAPA, of which I am vice president (an office without pay, which Cuban propaganda reported erroneously) but they did pay for my ticket.

My trip to Prague is funded by Amnesty International, because I was invited as a juror for a film festival they organized. I will go to Italy to collect an award that I had not been allowed to collect, which included–at that time–the plane ticket. From Italy I will go to Spain for the El Pais award, which also includes airfare. From Spain I go to New York, by invitation of students from two universities, which offer courses on computer science. From NY I will go to Miami to visit my sister, with airfare paid for with her money. From Miami I am going to Mexico to a meeting of the Inter American Press Association, IAPA, of which I am vice president (an office without pay, which Cuban propaganda reported erroneously) but they did pay for my ticket.