Translator’s note: This article by Regina is from the blog of Ernesto Hernandez Busto,, Penultimos Dias. It is a response to a commentary by Ernesto, “The Gap,” which appears below in translation.

The gap exists; but it also existed in the GDR the day before the wall fell, and in Romania, just as they started to boo Ceaucescu, and in the USSR and the rest of the disappeared countries of European socialist, except, perhaps, Poland. This allows me to be a little more optimistic with respect the moment of closing the gap.I love the ethics of the day after, precisely for something Dagoberto Valdes has called “the anthropological damage.” It is no coincidence that the enemies of the government have always been reduced to the human condition, a strategy means to depreciate the individual to the masses: it’s easy to crush a worm, eliminate the scum; in so many years of vulgar nationalist discourse, annexationism is the anti-Christ and the word “mercenary” has economic evocations that try to demonstrate profit at the expense of the country’s difficulties.

The postures toward a radical change are many, one commentator aptly notes that many very well informed will not lift a finger to support the change or to show solidarity with the opposition. I also see a paradox, because it’s said that those who live better would not bet on change. Within this small segment of the population that has grown rich, there are those who live not only according to capitalist standards, but who want more capitalism than can be found in today’s Cuba. They will not involve themselves in the change, but when it is secured, they would not oppose to it.

The moral gap is joined to another: What is the program of the dissidence? Pointing out the aberrant dysfunctionality of the government turns out to be much easier than developing a proposal to overcome the present moment. Parties, groups, points of view, in which everyone wants unity — but unity around their own idea — is a repeat of the political scheme they are trying to combat. I talk with or read — without prejudice — the opponents from across the spectrum. Eventually, I wouldn’t vote for them, but now they are fellow travelers whom I would not attack in public, doing the job of the political police. If I, who am a step beyond dissent, don’t feel myself represented, what can we expect from those who are unaware and/or waiting?

It’s hard to know what ordinary Cubans think. Those who interest themselves in being informed, seek out the information. Most are not interested but they can’t avoid it: changing the dial to hear their favorite program, waiting for the ball game or the soap opera, leafing through Bohemia magazine for the crossword puzzle, on the advertisements — from a poster in the pharmacy to the huge ones in the shopping centers… So I had the experience with two people situated among the discontented who didn’t dare do anything, of convincing them that the essence of the Ladies in White is not walking for money. Their arguments uncritically echoed what they’d seen or heard on Cuban mass media.

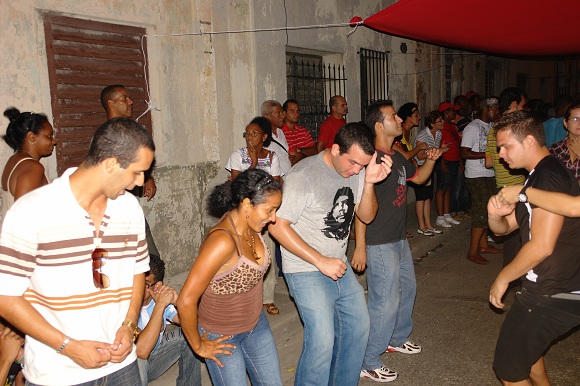

Are those who dance and shout in front of Laura Pollan’s house evil? They are university students, many think they’re doing the right thing, and undoubtedly consider themselves good people. Anthropological damage, because if you aren’t taught it at home, or don’t have the influence of a religious or fraternal organization, the difficulty is that it’s in the schools where kids today find their ethical compass. I also had a terrible experience with a friend of my son, young and intelligent, who expressed no qualms about participating in a repudiation rally.

The gap in favor of the government takes place within that immanence called time, against which our aged rulers can do nothing. And if the heterogeneity among the dissidence is notable, so should be that great “unity around me” — between secrets and whispers — of the officials and soldiers of the government. Another thing will be if it is for or against democracy.

Regina Coyula

Havana

21 April 2012

The Gap

by Ernesto Hernandez Busto, 17 April 2012

After five years of “aggregating” Cuban news from many sources and making visible to others what does not usually appear in the mainstream media, I think I’m in a position to notice a symptom — in my view a disturbing one — that I find in a good part of the discourse of our cyberdissidence: namely, the belief that to the extent that they fill the vacuum produced by the lack of information, the People will turn to the Good side, let’s say, as the veil that has prevented individuals from recognizing the definitive political Truth falls from their eyes. There is no suggestion, not even a suspicion, that this People already knows — or at least intuits — the Truth, and has chosen, instead, to stand on the side of its immediate interests rather than to openly align itself with civic activism and the defense of democracy.

The consensus of the Cuban opposition is undeniable: we can see it in the evolution of the discourse of Yoani Sánchez, Eliécer Ávila or the organizers of Estado de SATS, who have been critical of specific aspects of Cuban society (the press, transportation, housing, the state of the economy…), and in a political “consciousness” (to use a term from Marxist jargon) that calls into question the entire discourse of the legitimizers of the Castro regime. It is encouraging also to see how new faces have joined a growing youthful rebellion which is no longer a rare or isolated phenomenon.

But the essence of the problem remains, I believe, in a division that almost no one wants to talk about. This is the deep gap between Cubans with different interests as they face the prospect of a radical change, and of the inevitable price that this implies.

Cuban society today, like it or not, is more pluralistic than five years ago, especially in its pretexts to keep looking askance at the opposition, to not claim the rights of political representation or to keep oneself within a circle of silence and indifference, faced with the dissident ferment. Before, people did not protest out of fear, or because of the nationalistic carryover of “not giving arms to the enemy.” Now, in addition, many Cubans remain silent or don’t get involved because they prefer to defend their incipient economic interests (still at the margin of the State), their properties recently acquired legally, their professions, their subsidized and prestigious lives in the arts, their permissions to travel and all the perks power permits, for example, to artists or classes who consider the status quo less risky than the hypothetical scenario of a “New Cuba,” freer than today.

The difference between those who assume the risks of joining the opposition and those who remain on the sidelines is increasingly, I suspect, of an ethical nature. Deciding to join an act of repudiation is an ethical decision, as well as an immoral one. How does one come to be a “dissident” in Cuba today? And how is it that someone can support beating another person in public for thinking differently? Is it information or an idea about what is right or wrong? Who can force a person to dance, as if at a witches’ sabbath, outside a house under siege? These are the questions we have been asking, over and over again for far too long, without wanting to hear the most obvious and painful answer.

One of the few commentators who have focused on this question is the blogger Lilianne Ruiz, whose religious perspective makes her notably sensitive to the shamelessness of the new Revolutionary philistinism. These new Cuban Philistines, obsessed with the ordinary material goods that the Cuban State now allows them to pursue, feel the contradictory desire to do what everyone else does, and at the same time a febrile ambition to belong to a distinguished circle, in some form or another. It is doubtful they will choose to align themselves with the “radioactives.” Information doesn’t interest them; they are disenchanted with the Castro regime’s ideological propaganda and, at the same time, fascinated by commercial advertising. And the opposition lacks any marketing to offer them.

The fundamental problem facing Cuban activists and dissidents today is not just State Security. It is also this gap — social, ethical and even generational — that the Castro regime has managed to widen to their advantage.

Ernesto Hernandez Busto

Barcelona