![]() 14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 21 April 2019 — Luis Enrique Valdés has inhabited an obsessive spiral for four months. The reason is his efforts is to achieve a facsimile edition of La Edad de Oro (The Golden Age), written by José Martí; a version so perfectly identical to the original that readers will feel transported 130 years back in time when the four notebooks of this monthly magazine aimed at children were published.

14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 21 April 2019 — Luis Enrique Valdés has inhabited an obsessive spiral for four months. The reason is his efforts is to achieve a facsimile edition of La Edad de Oro (The Golden Age), written by José Martí; a version so perfectly identical to the original that readers will feel transported 130 years back in time when the four notebooks of this monthly magazine aimed at children were published.

This week he responded, via email, to some questions from14ymedio where he details the obstacles, joys and expectations that the project has generated.

14ymedio: Almost every Cuban believes he knows ‘The Golden Age’ by heart. What novelty will this new edition offer over previous ones?

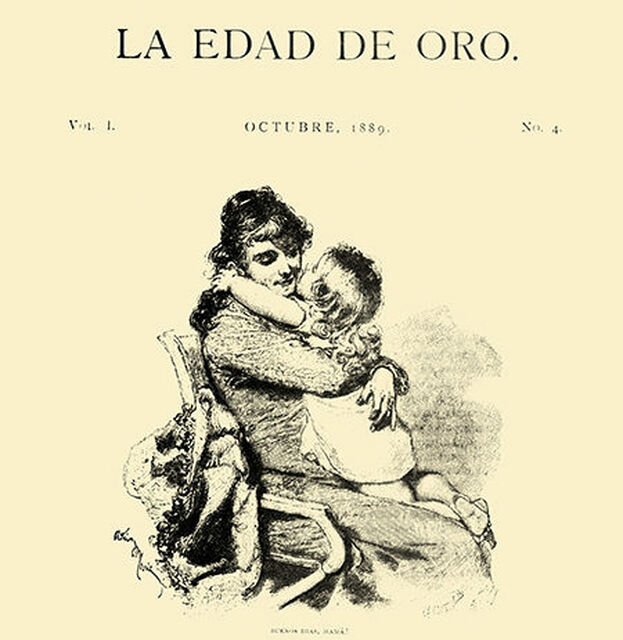

Luis Enrique Valdés: The Golden Age – just to say that it is a title given by A Dacosta Gómez, its first editor – appeared as a magazine. It was a “monthly publication of recreation and instruction dedicated to the children of America,” written entirely by José Martí, which only had four numbers: those corresponding to the months of July to October 1889. This 2019, so they are 130 years old. However, we have known it in the form of a book all this time.

In these 130 years it has seen the light in the original format only once. This is the Cuban edition in four issues, published in the year of its centenary. That edition, which to be fair I must say is very good, is almost impossible to find, it is very similar to the first and in its spirit we have been inspired, although starting now, for ours, the original numbers of 1889.

At that time it was stapled to a half-page white cardboard stamped with words from Luis Toledo Sande thanking the Office of Historical Affairs of the Council of State, as well as with the credits of that impression, that made the object itself not identical to the Martiana edition. There is something in it that was not in the 1889 edition.

We want this edition to be, for the first time in history, identical in everyway to what came from the hands of José Martí. This means that each issue will be an independent booklet with the exact appearance that José Martí gave to the magazine in 1889, without any additions or deletions in each one of them. We want them to be millimetrically equal to those in New York. That is why a fifth notebook will accompany the collection, as a presentation and study, so as not to touch the facsimiles with so much as a comma and it will include Marti’s correspondence about La Edad de Oro, as well as articles and announcements in publications of the period, unknown until now, and several subsequent essays among which is a very long one by Herminio Almendros.

14ymedio: What changes or vicissitudes did the book go through every time it was published until now?

Luis Enrique Valdés: In the letter known as Marti’s literary testament, written to Gonzalo de Quesada in Montecristi, on April 1, 1895, on the eve of his definitive return to Cuba to begin the struggle, he entrusted him with: “La Edad de Oro, or whatever part of it would suffer reprinting.” Martí’s request was fulfilled ten years after his death. Thus La Edad de Oro was published as a book in Rome in 1905. In Cuba it did not happen until 1932, when Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring published it, forty-three years after its appearance.

The first edition already had misprints, most likely associated with the work of copyists or printers. Most of them were inherited in successive editions. However, most of the current editions are perfectly corrected.

14ymedio: How was the process to get the original version available to the editors of this project?

Luis Enrique Valdés: It began with a worldwide search against the clock. I knew that the magazine had been distributed in five countries: the United States, Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela and Spain. We should not think that this distribution was massive. Absolutely. Martí spent a lot of work to find friends to help him distribute it. In Mexico, no. There was his “brother” Manuel Mercado, to whom he sent no less than 500 copies of the first issue.

In Cuba it came in through Guantanamo. There is still a sign on the site where the magazines were received. So the first thing I did was to consider that in the Public Library of New York there could be copies of 1889. But it was not like that.

I thought then that Dr. Eduardo Lolo, who has a critical edition of La Edad de Oro, could give me a tip about the whereabouts of some collection outside of Cuba. His response could not have been more discouraging: the only surviving collection was the one that Martí had placed in the hands of Quesada, which is currently on the island. That a man who had studied it so deeply told me this filled me with discouragement. However, his research is from the ‘90s. At that time the Internet wasn’t as extensive s it is now. I grabbed onto that to think that maybe there was an accessible collection somewhere in the world that Lolo did not know about.

It was not in the national libraries of any of the aforementioned countries, so I started looking into the libraries of others. Then National Library of France said they had them. Zoé Valdés helped me a lot in communication with them and yes, they supposedly had them. I received a notice with the clarification that, unfortunately, there was a cataloging error.

They had “a facsimile edition of 1989” that is not in the public domain and I had to ask the editors for permission. It was the edition I spoke of before; With all logic they had confused it with the original ones since to catalog the magazine they did not need to open it, as all the information – editor, author, year, month, number, city – everything appears on the cover. After thirty years and the high degree of conservation that documents can have in dry and cold countries, it was normal that they would confuse the 1989 one, which had aged very badly, with the one from 130 years ago.

It occurred to me to call my good friend María José Rucio who is the Head of the Manuscripts and Incunabula Department of the National Library of Spain. The first thing she told me was something I already knew: they did not have it. But she was immediately willing to lend a hand, giving me hope because librarians understand each other very well.

A few days later, in which I continued to delve into whatever library was going through my mind, she called me to tell me that a certain library in Madrid – that of the Agency for International Development Cooperation – which I had not yet looked at because I was focused on older libraries – claimed to have them. I called the AECID immediately.

A very kind gentleman who was already aware of my inquiries helped me. He looked at his catalog and assured me, firmly, that he had the originals. I was invited to spend the weekend in the Madrid house of my friend Thais Pujols, and I raced from Valladolid to arrive just before the library closed. It was a Friday.

I emerged from the mouth of the Moncloa Metro Station with an overwhelming emotion. I was running, crying, with Alberto Maceo on the phone. In just three minutes I was going to be before them at last. I arrived. I was helped by a being full of light: Rodrigo Sorando. He had bad news for me: his colleagues believed that it was a facsimile. I only had to see the backs to realize that, probably, they were not the ones I was looking for. And on opening them came the confirmation of the disaster: the same mistake as the French.

Rodrigo probably noticed that I was about to cry. My lips and hands trembled. I did not have the slightest hope of finding them, but he told me about a tool that could do in half a second what I had been doing for half a month on my own: search in all the libraries of the world at the same time. “You have it in Paris.” And I, no, no, which is the same as here, and then the light came, but a still dim light: “They’re in a Miami library!”

That weekend I could not contact them, but the next week the great news came: they were there!

Several Spanish institutions that by absolute discretion I do not mention, were willing to establish a library exchange to obtain high quality copies that I needed. That type of reproductions can reach a very high price, so an exchange like the one we were proposing, and the free gift later, smoothed the road a lot.

However, from Florida they did not hesitate in their generosity: they would freely give the copies with the characteristics that we needed, even if they were immense, without the need of the intervention of the Spanish institutions, with the only condition that this be confirmed in the special number of the edition. That’s how it will be and there you will be able to know, with details, who these people are who are so charitable and such excellent professionals.

In the middle of all this process, I managed to join my purposes with a person who is one of its fundamental pillars: Carlos Martín Aires. Besides being one of my greatest friends, he is also one of the best editors I know. His experience in editorial work is immense and his absolute dedication to work will ensure, with all certainty, La Edad de Oro remains exactly as we dream it.

14ymedio: Any anecdotes about what happened in recent months and what is there anything you can say now that the project has started?

Luis Enrique Valdés: I think the most beautiful anecdote is in the genesis of this idea. My friend Alberto Maceo, a brother to me, insisted on inviting me to spend the end of the year with him and his family in Flensburg, the city where he lives in northern Germany. What we couldn’t get out of our heads is that, to the joy of being together on holidays, we were going to add the emergence of such a beautiful idea and the best legacy of that trip. Alberto and Petra, his love, prepared the room usually occupied by their children for me. They have a bookshelf full of books there and, of course, I went to browse.

Among them are several editions of La Edad de Oro. All of them very unattractive. And as a throwaway comment I said: “What bad editorial luck has had La Edad de Oro!” Making a beautiful book is the result of a series of successful decisions. That magazine was conceived by Martí with immense good taste. Both the form and its contents were meditated and measured by him with exquisite manners that those later editions have sacrificed.

So Alberto, knowing that the edition of books is a weakness for me, snapped at me: “Well, make one that looks beautiful to you.” In the year that began the day after that conversation in Flensburg, this year, La Edad de Oro turns 130. So when Alberto told me that I was completely clear. And as soon as I set foot in Spain, I set out to find the originals, the only way to make a responsible facsimile edition. As I have called, all this time, the copies of that first edition of New York: “The originals.”

14ymedio: They have launched a fundraising campaign to get the five notebooks published. How is the initiative going so far?

Luis Enrique Valdés: As of now we’ve collected 30% of the total. We are still a long way from achieving it, but there’s still time. We can’t say we’ve got the wind in our sails, or that it is soporifically slow. There are days when it slows down more and I feel immense discouragement, others advance a little and hope returns.

If four hundred Cubans, or non-Cubans who are kind enough to contribute, join in this noble purpose, providing the minimum that the rewards indicate, we will achieve it. It doesn’t seem to be too much. It would be really sad that La Edad de Oro does not have this special edition with its 130 years because 400 Cubans have not agreed on it, after everything that this magazine and “the man of the Golden Age ” have given us as a legacy.

14ymedio: What a José Martí who lived so many years in exile returns in an edition also promoted by emigrants. More than coincidence?

Luis Enrique Valdés: I think that more than coincidence it is something natural. Those of us who carry on our shoulders the weight of not living in our Homeland, as he brought it, we are always aware of the memory of the Island. One leaves there with fragments on their backs.

This experience has led me to speak with hundreds of Cubans from exile I’ve directly asked to collaborate. Most tell me that, in their crammed suitcase, they left with their copy of La Edad de Oro. And those who did not, tell me that if there is something they remember with pain it is to have left it there. With those pieces one is built, as far as one can, a possible Cuba on this side. In that Cuba, as it is logical, this magazine created by José Martí is a temple of our childhood.

14ymedio: In times of ebooks, video games and mobile applications, what is the attraction for Cuban children to look at this magazine again?

Luis Enrique Valdés: As we have said, La Edad de Oro is an immense source of values. More than one person would be surprised to return to it to realize that it is a text of enormous appeal. It is true that today’s children are very enthralled by new technologies and this, properly channeled, is not bad. However, the charms that the printed book has always had, its touch, its smell, and this time the knowledge that what you have in your hands has the exact appearance of what Martí created for them, cannot be substituted with anything.

__________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.