![]() 14ymedio, Marcelo Hernandez, Havana, 9 January 2018 — “Did you buy the bread?” The shout comes from a balcony and is directed at a woman walking along a street in Havana.

14ymedio, Marcelo Hernandez, Havana, 9 January 2018 — “Did you buy the bread?” The shout comes from a balcony and is directed at a woman walking along a street in Havana.

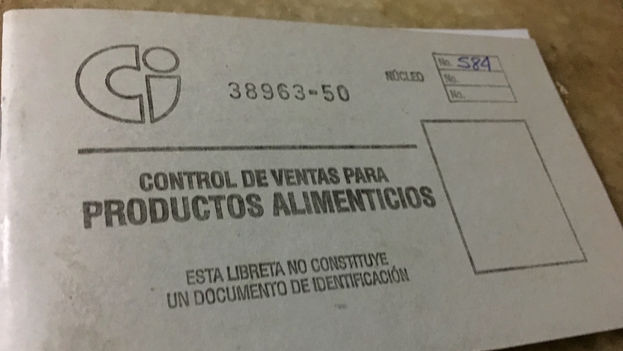

“The bread,” “the rice” or “the coffee,” with the article in front, always refers to the products that are sold through the ration book, an institution that will turn 56 in 2018.

A few decades ago, the rationed market served all Cubans, but with the growing social differences that have emerged on the island, this scenario is changing. At least two social groups buy little or nothing through the little booklet with its listing of subsidized prices, groups that are on the opposite ends of the economic spectrum: the new rich and the ‘illegals’.

Last December, officialdom finally put number to the Cubans who live in “illegal” situations on the Island: 107,200, of which 52,800 have been doing so for more than two decades, according to comments from Samuel Rodiles Planas, the president of Physical Planning, speaking to the Cuban Parliament.

These illegals are people who reside in a dwelling different from the registered address that appears on their identity card; as a result, many have difficulties in qualifying for their quotas in the rationed market, especially when they are far from their province of origin, because each nuclear family is assigned to one and only one bodega.

Roberto Macías has been “illegal” in Havana for seven years. He arrived from the distant city of Guantánamo, the province that loses the greatest numberof inhabitants every year due to internal migration: 9.1 per 1,000 people. Since then he has lived “without a ration booklet,” although his mother, back in Guantánamo, collects sugar and rice from the rationed quota to send him every three months.

The majority of Cuban migrants within the island choose the capital as their destination – where an average of 15,000 new residents arrive each year – followed by Matanzas, Artemisa and Mayabeque, according to data from the 2015 Cuban Population Yearbook and published by the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI).

Not only must these internal migrants say goodbye to their homes and family members in search of opportunities, but many of them have to give up the products from the rationed market. “I have not managed to have an address in Havana that is not provisional, and without that I can’t transfer my ration book here,” laments Macias.

The Guantanameran was born in 1963, just one year after the creation of the Ration Book as a system of subsidies and food rationing intended to guarantee a basket of affordable basic products for all Cubans. It was almost an emergency measure, like the one that was taken in some European countries after the Second World War, but in the Cuban case it may soon become a system that has lasted for six decades.

At that time, the imposition of a rationed market was justified based on the “imperialist” threat of the United States and its trade embargo. However, economist and professor Carmelo Mesa-Lago, in his studies, also attributes it to the collectivization of the means of production and the freezing of the prices of consumer goods carried out by Fidel Castro’s government.

Macías has visited the Consumers Registry Office (OFICODA) in Havana’s Cerro neighborhood where he currently resides, but the answer is always the same: “If you do not have the address on your identity card we can not sign you up for the ration book,” they respond.

Although over the years the variety and quantity of products offered through rationing has been significantly decreasing, the State still spends more than one billion pesos a year in subsidies for these foods which are barely enough for a third of the month; in a country that imports about 80% of the food consumed, the cost figure is not negligible.

With meager portions of rice, chicken, sugar, milk, oil, eggs, beans and the daily quota of bread provided on the ration book, it is difficult to survive, but many families use it as a basic support to which they add the products they must buy at high prices in hard currency stores, agricultural markets or through informal trading networks.

Macias, however, does not have even that base. “It’s very hard because every day I have to invent what my family is going to eat and when I can’t find a peso I’m totally at sea,” he says.

This week, he has to go and look for “the box” with the quarterly shipment that arrives for him by rail from Guantanamo with the quota of grains and rice that were allocated to him for October, November and December. His mother has warned him that on this occasion “she had to take a little for herself during the end of the year,” he says.

A few yards away from the place where the Guantanameran resides in Havana lives another family that does not buy the products on the ration book, but for a very different reason. The husband is a musician with a salsa orchestra, the wife is a nationalized Spanish citizen, and the couple has an economic affluence that allows them to dispense with subsidized food.

“Years ago I handed over to an aunt of mine the right to buy my shares on the ration book because she needs it much more,” says Katia Lucia, 48. Among the reasons she gives is that she doesn’t want to “keep standing in line to buy at the bodega” and “the quality has fallen a lot,” so she “spends a little more on food but eats better.”

La cubañola travels frequently to Cancun to stock up on products. “The ticket is cheap and I bring everything from concentrated tomato puree to small soup cubes, as well as cheese, butter and toilet paper.” With three trips a year, plus what her husband earns as a musician, she says they can “resolve” their needs “without appealing to the ration book.”

But the family of Katia Lucia and her husband continue to qualify for the same products every month as do the most destitute. A contradiction that Raul Castro himself lamented in 2010 when he said that “several of the problems we face today have their origin in this measure of distribution that (…) constitutes a manifest expression of egalitarianism that benefits equally those who work and those who do not.”

“What they give you, take it,” laughs Katia Lucia recalling a very popular phrase that reflects like no other the cronyism that rationed distribution has generated. “I’m not going to leave those foods in the bodega. What for? To be picked up by someone else?” she explains to 14ymedio. “I prefer to give it to my aunt or give it to the dogs, but if it ‘belongs’ to me I will not leave it behind.”

During the public debates on the Guidelines for Economic and Social Policy, in 2010 and 2011, the possible elimination of the ration book was the topic that provoked the most comments and fears.

Maintaining it is like dragging a weight that the stagnant economy can barely sustain due to the heavy subsidies involved in selling food at very low prices. Some experts suggest limiting access to the ration book to the people most in need so that everyone can have a greater amount of food.

The economist Pedro Monreal believes this is the way to go and he proposes in his blog “a shrewder budgetary redistribution.” For example, if the number of beneficiary households is reduced to 3 million instead of the current 3,853,000, the subsidy for each family increases by 28.5%. With 2.5 million households, the subsidy for each one grows by 54%, and with 2 million, the increase is 92.6%.

There remains a question in the air, which Monreal has not yet addressed in his blog: what will be the criteria to reduce the number of beneficiaries “without setting off an extended social unrest”?

__________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.