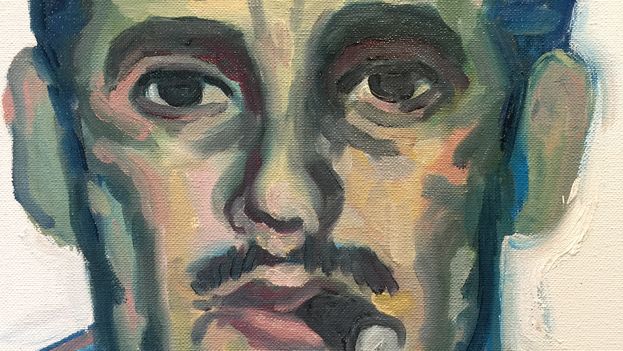

![]() 14ymedio, Yaiza Santos, Mexico, 27 June 2015 – Painter and writer Juan Abreu (b. Havana, 1952) has taken on the inordinate task of painting, one by one, all those executed by the Castro regime. The work in progress is entitled 1959 but encompasses 2003, the year in which Lorenzo Capello, Barbaro Sevilla and Jorge Martinez were sentenced to death in a summary trial, accused of “acts of terrorism” after trying to reroute a passenger ferry to escape to the United States. They were the last executed by the Cuban government. “Let it be known,” says Abreu.

14ymedio, Yaiza Santos, Mexico, 27 June 2015 – Painter and writer Juan Abreu (b. Havana, 1952) has taken on the inordinate task of painting, one by one, all those executed by the Castro regime. The work in progress is entitled 1959 but encompasses 2003, the year in which Lorenzo Capello, Barbaro Sevilla and Jorge Martinez were sentenced to death in a summary trial, accused of “acts of terrorism” after trying to reroute a passenger ferry to escape to the United States. They were the last executed by the Cuban government. “Let it be known,” says Abreu.

The project emerged, he says, recently, by chance: “I was doing some paintings that had to do with the firing squads in Cuba, because I was struck by the character, the loner that they are going to kill. I had seen some paintings by Marlene Dumas of Palestinians and then I approached the subject. When I started researching, suddenly the faces of all these people began to appear. I began to look at the faces and read, and suddenly I realized that I was going to have to paint this. Not only as a kind of pictorial adventure, which it is, because of the quantity of portraits and the complexity of the genre, but also because it seems to me that I have a certain moral responsibility.”

Of the executions in Cuba, he continues, “It is an untold story. Not only untold, but also they have tried to hide it, and when they have spoken of it, the effort has always been to discredit the protagonists, branded as outlaws or murderers. These accusations lack any kind of historical evidence. They were people who rebelled, the same as Fidel Castro rebelled against Batista, they rebelled against Fidel Castro.”

The death penalty, explains Abreu, was not contemplated in the 1940 Constitution which the Revolution originally claimed it would restore: “They [the Castro regime] imposed it. The trials completely lacked any kind of safeguard. Sometimes even the lawyer spoke worse of the condemned than the prosecutor did. They were Soviet-style trials: you already knew you were guilty as soon as they caught you; you knew that they were going to kill you or put you in jail for thirty years.”

In order to gather as much information as possible, he contacted some of the few people who have devoted themselves to the topic in the United States, like Maria Werlau, from the Cuba Archive, or Luis Gonzales Infante, a former political prisoner who sent Abreu his book Rostros/Faces, where he compiles names and photos of those dead by execution, from hunger strike or in combat during the El Escambray uprising, those seven years that historians like Rafael Rojas consider a civil war and that Fidel Castro called a “fight against bandits.”

Other documents he has found easily on the Internet, like videos from the period and photographs from the free press that still existed in Cuba when the Revolution triumphed. Hence, the executions of Enrique Despaigne, doubled over by two shots at the edge of a ditch, or Cornelio Rojas, whose hat flew together with his brains against the execution wall. Abreu confesses that what impacted him most was “the gruesomeness and cruelty” of some of the cases.

Like that of Antonio Chao Flores, who at 16 years of age fought against Batista – the magazine Bohemia had him on its cover as a hero of the Revolution – and at 18 years of age he fought against Castro, and was required to drag himself from his cell in the La Cabana fortress to the execution wall without the leg he had lost in combat because the guard took his crutches from him. “It is from the savagery of the system’s punishment mechanism that one feels fury that all this that has happened has been forgotten. If I was Chilean or Argentinean, this would immediately demand attention.”

Abreu says that the project is becoming gigantic and that he cannot stop. For now, he has painted some twenty of the 6,000 total that he estimates were executed in Cuba in that almost half-century. Via a Youtube video [see below] he seeks photographs from all who may be aware of any victim.

No one has answered him from Cuba – “There, to have a relative who was a prisoner or who had been shot, was anathema, because of the amount of false propaganda against them” – but people have answered him from the United States. For example, one sent him the photograph of her neighbor in Cuba, whom she knew from childhood, who used to greet her kindly and whom she eventually learned was made a prisoner and executed. It was when media control was complete, and an absolute silence, when propaganda was not served, covered these kinds of cases.

“The death penalty in Cuba has always been used as a means of social threat. When they ask me, “But why has the regime lasted so long?” I answer: It has lasted for many reasons, but among them because it is a system that kills. You know that they will kill you. And there is no safeguard: There is no judge or lawyer who can defend you, and if they decide that you have to be killed, they will kill you. And if you do anything against the system, they will kill you. Death is a very effective deterrent.”

Forged by the generation of his friends Reinaldo Arenas and Rene Ariza, Abreu says that “kind of strange fury” that he feels about Cuba has not abandoned him since he left the Island with the Mariel Boatlift, and that after so many years, he has decided to stop fighting it. “Towards Reinaldo (Arenas), for example, it seemed to me a great betrayal. In our last conversation, two or three days before he killed himself, we were talking about that precisely, and he told me, ‘Up to the last minute. Our war with those people is to the last breath of life.’ It surprised me a little why he was saying that to me, but of course, he already had his plans. Maybe I like lost causes, but I will continue infuriated.”

By way of poetic revenge, he hopes that his project 1959 – which he calls “completely insane” – ends up one day in a museum. “Because a hundred years from now, when no one remembers who Fidel Castro was, these paintings will be here and people will say, ‘And what about these, so pretty?’ And that, truthfully, is very comforting.”

Translated by Mary Lou Keel