![]() 14ymedio, Generation Y, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 19 October 2017 – We see him leaning over, a lost look in his eyes. He is mortally wounded and the bronze captures the second that separates him from immortality. The replica of the José Martí statue that has been in New York’s Central Park since 1950, now has a place in Havana. On Thursday afternoon, under an intensely blue sky, we can see his contours sparkling and the pedestal shine. Also noteworthy are the unpardonable mistakes on the commemorative plaque.

14ymedio, Generation Y, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 19 October 2017 – We see him leaning over, a lost look in his eyes. He is mortally wounded and the bronze captures the second that separates him from immortality. The replica of the José Martí statue that has been in New York’s Central Park since 1950, now has a place in Havana. On Thursday afternoon, under an intensely blue sky, we can see his contours sparkling and the pedestal shine. Also noteworthy are the unpardonable mistakes on the commemorative plaque.

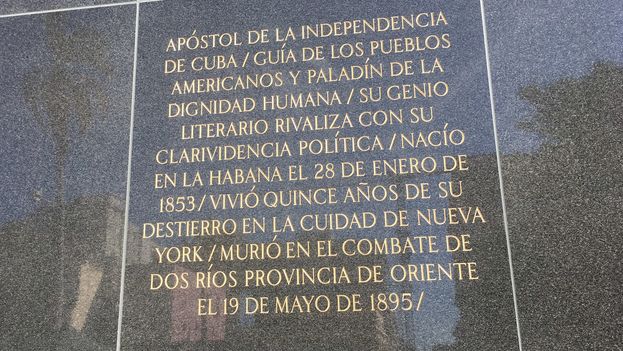

City is spelled ”cuidad”– similar to the word for “care” – instead of “ciudad.” Nacío – an ugly attempt at “he was born” – misplaces the accent and almost flirts with “I was born,” but in fact is not a word at all. These are two of the “pearls” carved into the shining black granite that, as of this week, thousands of Cubans and foreign visitors will read on the monument. The devils of misspelling and lack of grammatical rigor have played a trick on the man who loved words and cultivated them with a venerable passion.

More than fifteen feet high and weighing three tons, the piece has been placed a few steps from the old presidential palace. Its lovely lines are a copy of the work conceived by the sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington that stands in a small area at the southern end of the New York City park, along with monuments to Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín.

The mistake-plagued inscription on the Havana piece – no one has clarified whether it came with the statue or is a local production – is an insult to the poet of Versos Sencillos, Simple Verses. To write on a piece of paper a phrase that has not been carefully reviewed is one thing, but to sculpt it in stone is to make a monument to improvisation and to display a huge disdain for the language.

Some will say that they are only small details, but a graduate in Philosophy and Literature deserves – at the very least – that a good editor check his lines.

Nor does the equestrian statue come at an easy time. Forged in Philadelphia, it was carried to the Island in the midst of a growing escalation of tensions with the United States. The figure that should represent the confluence between two nations, as Martí did during his life, is now a reminder of a diplomatic meltdown that fell short and of a time that was irretrievably lost.

Thus, during its placement there was no lack of jokes from the nearest neighbors about whether the man we Cubans call the “Apostle” had asked for a visa to enter the country. The humor never fails, nor the sad jest that evokes the difficulties that Cubans currently face to travel to their northern neighbor, after the scandal of acoustic attacks about which there are more questions than certainties.

As an irony of life, one of the workers who finished some details around the monument proudly displayed a T-shirt with the banner of stars and stripes. As with the spelling mistakes, no one saw it, no official came to check on what was going on.