Eloy Viera, from El Toque, published by Cubalex, 19 November 2019 — On October 1st, 2019, Jose Daniel Ferrer, leader of the opposition organisation Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU, by its initials in Spanish), was detained by the Cuban police in his home. His family stated that, for a period of several days, they were unable to verify his whereabouts or physical condition.

On October 29th, the United Nations Committee Against Forced Disappearance issued a “request for urgent action” to the Cuban government, asking for, among other things:

To clarify immediately what has happened to Jose Daniel Ferrer Garcia, and where he is.

To inform his family members and representatives … what has happened and where he is, and … permit his family and representatives to make immediate contact with him.

In the event of his precise location being unknown, to take all necessary actions to clarify where he is and what has happened to him … including the adoption of a comprehensive and exhaustive strategy to find him and to investigate his alleged disappearance.

If his detention is confirmed, to bring Mr Ferrer Garcia immediately before a judge, having informed him precisely of what crimes he is accused, and affording him access to a lawyer.

The United Nations Committee’s pronouncement is based upon the Convention relating to the Protection of Persons against Forced Disappearance. Cuba signed and ratified the Convention in the years 2007 and 2009 respectively, as a result of which, in accordance with International Law, it has assumed the expectations and obligations of that legislation.

According to the Convention, “the arrest, detention, kidnapping, or any other form of deprivation of liberty, whether resulting from the activities of agents of the state, or those acting with the authorisation, support, or acquiescence of the state, accompanied by a failure to recognise said deprivation of liberty or the concealment of the situation or whereabouts of the disappeared person, depriving him of the protection of the law”, is a forced disappearance.

ON WHAT BASIS CAN THE COMMITTEE AGAINST FORCED DISAPPEARANCE ASSUME THAT THE CASE OF JOSE DANIEL FERRER MAY CONSTITUTE A FORCED DISAPPEARANCE?

The legal instrument intended to protect the individual against forced disappearance and arbitrary detention is habeas corpus.

Habeas corpus in its classical sense provides a direct form of protection for the individual in terms of personal liberty and physical condition. In order to be able to confirm that a person has benefitted from a habeas corpus process which meets international standards, it is essential that the person detained be presented before a judge as quickly as possible.

Habeas corpus does not just permit the assessment of the legality of a detention or disappearance, but also serves as an instrument by which an impartial entity (a judge) may consider whether the authorities, or those appointed by the state, have respected the individual’s life and physical condition. The physical appearance before a judge of the detainee prevents the location of the detention being kept secret, and protects him against torture or other cruel, degrading or inhuman treatment or punishment.

After more than 15 days’ detention, Jose Daniel Ferrer’s family members claimed that they did not know where he was being held, his physical conditions and the crime of which he was accused. For this reason, they lodged an application for habeas corpus before the Popular Provincial Tribunal of Santiago de Cuba.

They hoped to obtain the support which “theoretically” is offered by Cuban law in such situations, as set out in the currently applicable regulations which acknowledge that a judge who is in receipt of such an application may:

Order the authority, or official, having charge of the detainee, to present him, at the time and date specified, before the Tribunal, within a space of 72 hours.

Require the same authority, or official, to provide a written report indicating when and why he was detained.

If the judge is informed that the person in question is not being detained by that authority, he may require anew that it be clarified whether, at any time, he was so detained, and whether he was transferred to another authority or official, indicating their identity.

On presentation of the detainee and the report, he may arrange an oral hearing in order to hear the interested parties and assess the evidence presented. Following this hearing, the judge is in a position to take an informed decision, which may or may not lead to the freeing of the detainee.

Nevertheless, the application presented was responded to by way of Order 39, dated October 18th, 2019, in which the judges declared that the application for habeas corpus had no merit.

The judges, without having undertaken any of the aforementioned procedures, considered that “the application has no merit” because Ferrer is being processed by way of a Preparatory Phase Action initiated on October 3rd, 2019, covered by an Act of Detention, dated the first of the said month. Moreover, they considered that his detention is in response to A Precautionary Measure of Pre-trial Detention issued by a prosecutor on October 7th, 2019.

The unofficial versions of the announcements, which were circulated afterwards by the Committee on Forced Disappearances, and the campaign in favour of the release of Jose Daniel, as well as the nuances which were introduced, do not detract from any of those arguments.

So, in the absence of any official written pronouncement to clarify the current situation of the leader of UNPACU, the assumptions of the Committee Against Forced Disappearances are not unfounded.

IS WHAT HAS HAPPENED WITH THE HABEAS CORPUS OF JOSÉ DANIEL FERRER THE EXCEPTION, OR THE RULE?

The report issued in Cuba on the Periodic Assessment of Human Rights (by the United Nations) in 2018, stated that “there is an immediate right of application for habeas corpus to challenge the illegality of deprivation of liberty and detentions … between 2010 and June, 2017, the tribunals considered 156 applications for habeas corpus. In 8 of them it was agreed the application had merit and the detainee was immediately released”.

These numbers, rather than demonstrating the ethics of the Cuban authorities, and the absence of arbitrary detentions or forced disappearances, evidence the inefficiency of Cuban habeas corpus and its resultant lack of use by legal professionals.

Because of the design of juridical regulations in Cuba, it cannot be considered that “judicial supervision”, which is essential in habeas corpus, is a guarantee for those deprived of liberty or who are detained. In Cuba, the supervision of the legitimacy and legality of such situations is not in the hands of a judge, but rather in those of the party with the principal obligation of investigating crime and representing the state in achieving a judgement: the prosecutor.

The decision proffered by the Provincial Popular Tribunal of Santiago de Cuba in response to the habeas corpus application presented in favour of José Daniel Ferrer, demonstrates this. What the judges did, and do, in this , and in the majority of these cases, is deny the person affected the opportunity of an “impartial” tribunal to assess the reasons for his detention, the circumstances in which it arose, and its legality.

The Cuban regulations consider that all acts of the police and instructions approved by the prosecution are legal, and do not need to be supervised or evaluated by the tribunals. Art. 467 of the Law of Penal Procedure establishes that: “applications for writs of habeas corpus shall not proceed in cases in which the deprivation of liberty results from a sentence or order of pre-trial detention in respect of a criminal act.

That provision allows judges not to analyse the application presented in favour of José Daniel Ferrer, and so, not to require his presentation before them, not to mention the crime of which he is accused, and not to assess his personal circumstances or to define his place of detention.

It would have been good if the judges, rather than hold that the application “had no merit” had expressed what really had happened: that they were unable to decide whether or not the interested party was right. They took advantage of the ability granted them by law and did not seek to establish the details or to evaluate the arbitrariness of a detention which has been described as politically motivated.

If they had done the opposite, then probably the Committee Against Forced Disappearances would not have needed to present its petition for urgent action. Nevertheless, the way most of the Cuban penal process is designed, including that of applications for habeas corpus, detached from international standards of due process, will ensure that there is much to occupy the attention of the United Nations Human Rights Council Working Group on Arbitrary Detention Working Group.

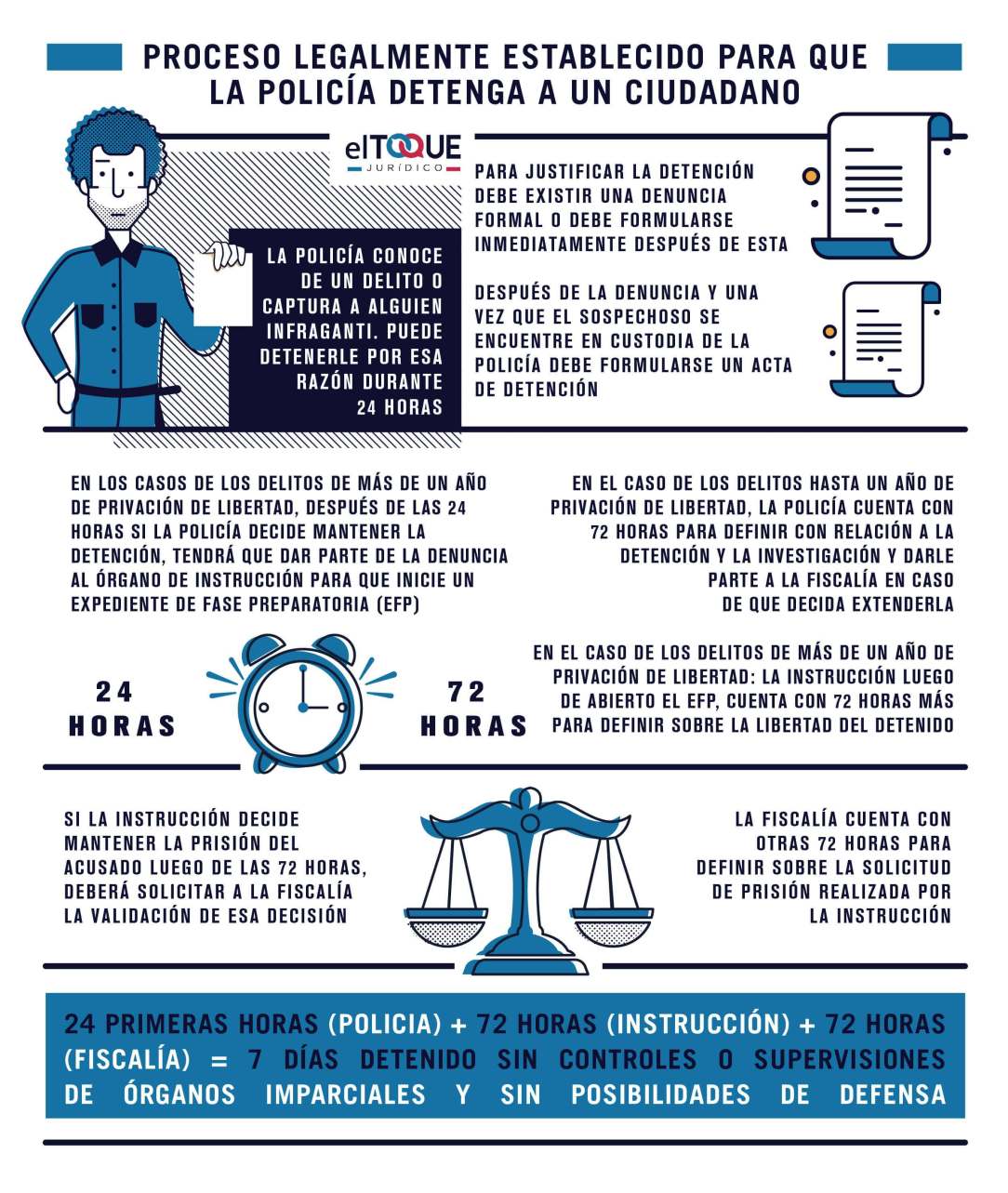

ESTABLISHED LEGAL PROCESS FOR POLICE DETENTION OF AN INDIVIDUAL

The police are aware of a crime, or capture someone in the course of its commission. For this reason, they may detain for 24 hours.

In order to justify the detention, there needs to be a formal report, or it should be prepared immediately afterward.

Following the detention, and once the suspect is in police custody, an Act of Detention should be prepared.

____________

In the case of offences attracting an award of more than 12 months´ loss of liberty, then, following the 24 hours, if the police decide to continue the detention, the matter must be reported to the instructing body, for the preparation of an Initial Hearing Report.

In the case of offences attracting an award of up to 12 months´ loss of liberty, the police have 72 hours in which to determine the detention and the investigation, and to report to the prosecutor in the event of wishing to extend it.

In the case of offences attracting an award of more than 12 months´ loss of liberty: following preparation of the Initial Hearing Report, a furtheR 72 hour period is available for the determination regarding the release of the detainee.

___________

If the decision is to continue the detention of the accused beyond the 72 hour period, the Attorney´s office should be requested to validate such decision.

The Attorney´s office has a further 72 hours to decide such application.

_____________

INITIAL 24 HOURS (POLICE) + 72 HOURS (INSTRUCTION) + 72 HOURS (ATTORNEY) = 7 DAYS DETENTION WITHOUT CONTROL OR SUPERVISION BY IMPARTIAL ENTITIES, AND WITHOUT POSSIBILITY OF DEFENCE

Translated by GH